The U.S. House of Representatives passed a tax overhaul Nov. 16 that would impact the income from the University’s endowment, the tuition assistance program for employees and graduate student tax rates. The bill would also reduce tax incentives for charitable giving to the University and eliminate the student loan interest deduction. The House tax package shares many provisions with the Senate version, which was approved by the Senate Finance Committee Nov. 16.

Taxing University earnings

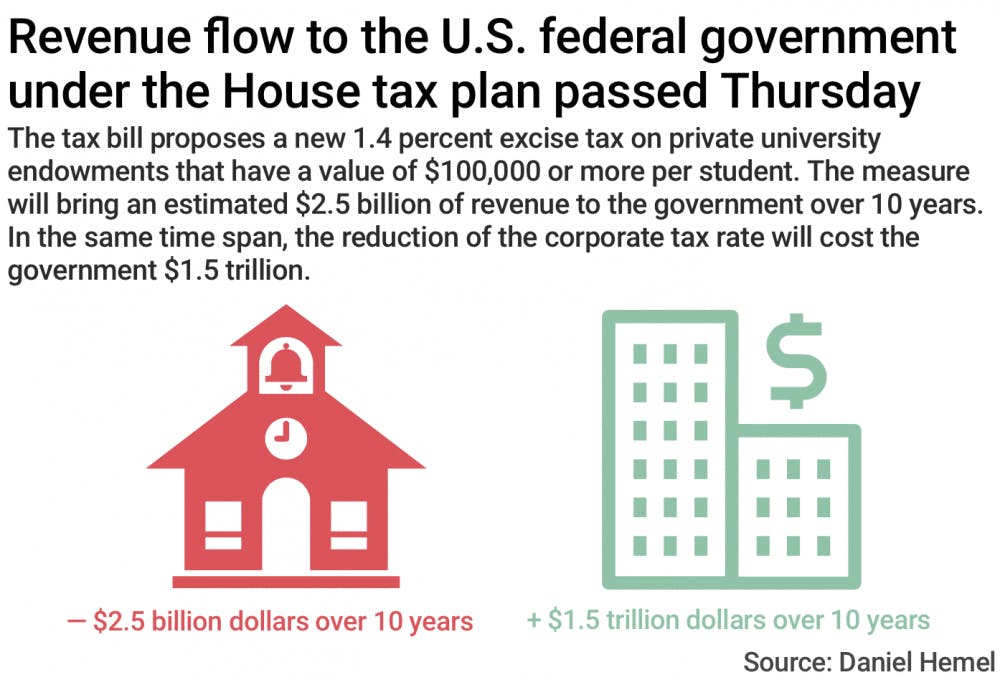

Both the House and Senate bills would impose a 1.4 percent annual excise tax on the net investment incomes of private universities with assets of more than $100,000 per student. This provision would not affect Brown significantly, said Daniel Hemel, assistant professor of law at the University of Chicago. Based on the endowment’s 13.4 percent return in fiscal year 2017, Brown would pay a tax equal to 0.2 percent of its endowment, he added.

The tax paid by the University “could be in the range of anywhere between a little over $3 million and a little over $6 million per year,” said Provost Richard Locke P’18. Thirty-two percent of the endowment’s earnings “go just to scholarships and fellowships, and another 20 percent goes to supporting professors,” Locke added. The excise tax would “really hurt people and support for people.”

“At least in the revised version of the House bill,” the excise tax is “limited to about 70 institutions across the country,” said Patrick Thomas, director of Notre Dame Law School’s tax clinic.

As such, this provision would not generate a significant amount of money for the government, yielding only $2.5 billion between 2018 and 2027, Hemel said. For comparison, “the total cost of the reduction in the corporate tax rate is about $1.5 trillion” over the next 10 years, he added.

Financial considerations are not the only motivation behind the inclusion of the excise tax, Hemel said. “Several Republican senators have been vocal critics of large universities — Ivies and others — that they seem to see as bastions of the elite,” he added. Among the provisions that impact higher education, the excise tax is the most likely to be passed, Hemel said.

“Of all of the provisions, (the excise tax) probably has the least amount of effect on the least amount of people and could potentially generate some bipartisan support,” Thomas said. Politicians on both sides of the aisle worry that universities with large endowments make “risky” or “secret” investments in hedge funds or overseas markets, he added.

Taxing graduate student tuition

Under the House bill, waived graduate student tuition would be treated as taxable income. Graduate students currently pay taxes on their annual $30,000 stipends, which puts unmarried students roughly in the 15 percent tax bracket, Thomas said. If their waived tuition — generally about $50,000 per year — was interpreted as income, “that pushes them up into the 25 percent tax bracket,” he added.

The taxing of waived tuition “would devastate graduate programs everywhere” and “basically wipe them out,” Locke said.

If the provision passes, graduate students at the University will be left with about $13,000 of their stipends to live on annually, said Dennis Hogan GS, a member of Stand Up for Graduate Student Employees and the University Resources Committee. At the URC public forum held by Locke November 16, it was revealed that the total estimated federal and state tax per student would be $16,830 if the House tax plan goes through. The taxing of waived tuition “would result in graduate education becoming the exclusive privilege of an elite class, only accessible for those with means to support themselves on what in some cases would be poverty wages,” wrote Aaron Jacobs GS, a member of SUGSE,in a follow-up email to The Herald.

The tax would “triple or quadruple the tax burden on graduate students,” Hogan said.

“Regardless of whether you consider yourself on one end of the political spectrum or the other, this one line item in this bill can seriously affect graduate students of a very wide range of financial backgrounds,” said Andrew Lynn GS, chair of student life for the Graduate Student Council. “So I urge graduate students to not consider this a partisan issue.”

As the Senate bill does not include the provision to tax waived tuition, the provision is unlikely to pass, Hemel said.

“There is a lack of clarity about (what) the precise effect” would be should the provision pass, Thomas said. Universities might find a way to exclude waived tuition from taxable income, or the Internal Revenue Service might take a position that precludes graduate students from paying higher taxes than they currently pay, he added.

“It’s hard to believe that the House really intended to impose a tax on the tuition sticker price for every PhD student in the country,” Hemel wrote in a follow-up email to The Herald. “If that did happen, it would have serious negative consequences for the ability of U.S. universities to compete for the world’s top grad students.”

However, in the short term, the proposed tax may deter prospective graduate students from pursuing graduate education, Thomas said.

Taxing tuition assistance and additional provisions

To help employees pay for the undergraduate tuition of their dependents, the University provides its employees with up to $11,700 annually per dependent through its Tuition Aid Program. This tuition assistance would be taxed under the House bill, Locke said, adding that scholarships for employees wishing to take classes at Brown and elsewhere would also be taxed. The provision would undermine “some of the core benefits that we give employees at Brown,” he said.

The House bill would also reduce incentives for charitable giving to the University, Hemel said. Under the bill, “we’ll go from a third of people having a tax incentive to give to charity to probably less than a tenth,” he said. This “will matter for universities like Brown, which are largely funded by charitable giving.” But the University’s largest donors will still likely be incentivized to give to Brown, Hemel said.

Interest paid on student loans would also no longer be tax deductible under the bill, and the Lifetime Learning Credit, a 20 percent tax credit on up to $10,000 in tuition expenses, would be repealed.

Bringing down the bill

In partnership with Ivy-plus peer institutions and higher education associations, the University is participating in lobbying initiatives to address provisions of the House and Senate bills that affect higher education, said Al Dahlberg, assistant vice president of government and community relations for the University. Organizations such as the American Association of Universities, American Council on Education, Consortium of Liberal Arts Colleges and National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities “can amplify our ability to communicate and influence legislation,” Dahlberg added.

In response to the announcement of the proposed excise tax on endowment income, the University collaborated with these organizations and Ivy-plus schools to “gauge the legislative intent and the impact it would have on our institutions,” Dahlberg said. He added that the goal is to illustrate the effect of the excise tax to members of Congress not just as “a dollar figure” but also in terms of its “impact on affordability” and on “the research that fuels innovation” and “creates the technologies critical for national defense, for economic development and for advancements in medical research.”

“Our hope is that once members hear and see the full extent to which the policies will limit accessibility and affordability they will reconsider,” wrote Pedro Ribeiro, vice president for communications at the Association of American Universities, in an email to The Herald. “It’s one thing to put policy down on paper, it’s another thing entirely to actually see the impact.”

Staff members of the University’s government relations group share Brown’s objections to provisions of the tax bills with staff in “our congressional delegation,” Dahlberg said. President Christina Paxson P’19 has called U.S. Senators. Jack Reed, D-R.I., and Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I., and is in the process of speaking to other members of Congress, he added.

As “GOP members are going to be critical to influencing the bill,” the University is “working closely with the schools that are in red states and have moderate GOP members who understand what’s at stake — who believe firmly in higher education,” Dahlberg said. Brown and other Ivy-plus institutions are trying to communicate with these members of Congress and their staff members through alums with congressional connections, he added. Paxson has asked for the assistance of the University’s Corporation in “reaching out to influential members of Congress,” Dahlberg said.

The Senate bill vote will most likely take place the week after Thanksgiving and is the University’s “best opportunity to influence this legislation,” Dahlberg said, adding that the University is currently focusing most of its lobbying efforts on the Senate.

On Nov. 14, SUGSE organized a phone bank — spearheaded by Lubabah Chowdhury GS and Hilary Rasch GS — during which graduate students called their representatives in Congress to inform them of the effects of the tax bill on graduate workers and their communities.

Though not an official sponsor of the event, the GSC supports the “dissemination of tax information and contacting the Congresspersons,” Lynn said. The council is currently drafting a letter to be sent to members of Congress, he added.

“Graduate students themselves are a fairly potent political force,” Hemel said.

Planning for passage

Until a specific bill is passed, the University doesn’t “actually know what we should be responding to,” Locke said. “But we’re spending a lot of time thinking about different scenarios and preparing for them.” Efforts are focused on determining what costs the bill would generate, where the resources to defray these costs would come from and whether there are legal ways to minimize the impact of the bill, he added.

While the URC is continuing its work on a budget begun before the House bill was publicized, “we’re also going to try to figure out what’s plan B,” Locke said. This involves determining the economic impact of the passage of all or some of the bill and then formulating an alternative budget “that allows us to meet these new expenses,” he added.

If graduate student waived tuition was taxed, ensuring that students still had an adequate stipend would cost “enormous amounts of money” — perhaps around $35 million, Locke said.

“There are ways that we could still be considered graduate students and have our tuition covered but maybe redistributed in a way that is not taxed so that the government doesn’t see it as income,” Lynn said.

“This is a huge challenge and one that we didn’t predict or we didn’t foresee a couple of months ago, … and I feel very proud to be in a community of faculty and staff and students who are all kind of rallying to try to figure out how do we meet this challenge,” Locke said. “I feel like people are really coming together to work together on this.”

— Additional reporting by Emily Davies.