Christine “Lady Bird” McPherson loves her mother. But she doesn’t like her mother.

The daughter and mother duo, played superbly by Saoirse Ronan and Laurie Metcalf, respectively, are constantly at each other’s throats, always bickering and nagging and pushing their relationship toward a fatal precipice. But they are also kindred spirits, albeit contradicting ones. They weave in and out of each other’s lives, slowly revealing themselves as a messy, imperfect and wonderfully human mother-daughter pair. Perhaps, though, “weaving” is too gentle a term for Christine and her mother, Marion. Rather, they explode onto the canvas of their shared life, crashing into each other in a series of cluttered, wearying and ultimately touching interactions.

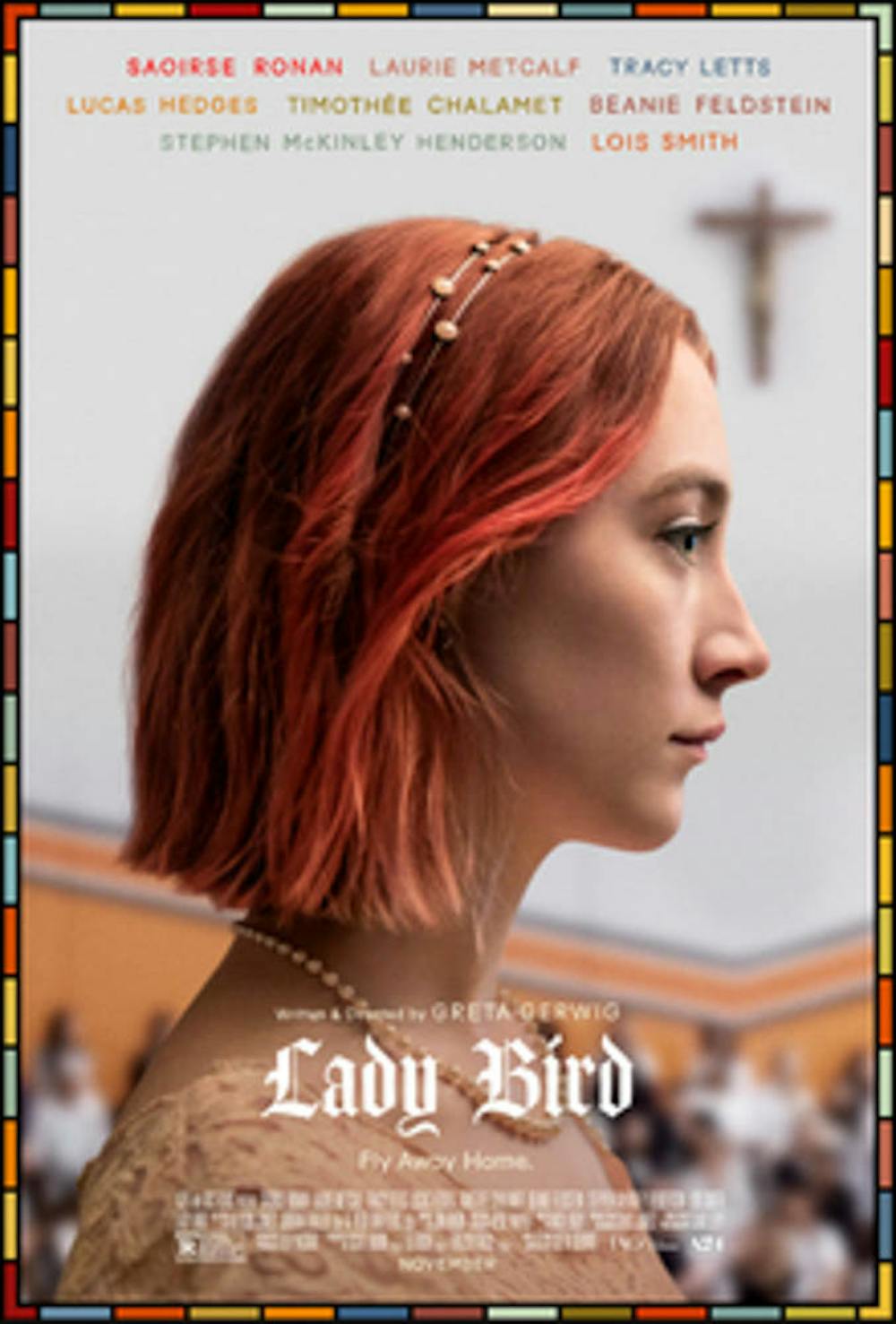

But alas, “Lady Bird” deserves elegiac tributes and immediate consideration for a place amongst the pantheon of cinema’s great bildungsromans. It is also a tour de force from first-time director Greta Gerwig, who also wrote the accompanying screenplay. It’s a lot of responsibility to juggle, but Gerwig manages to get just about everything right: From the clever and perceptive dialogue, to the film’s narrative pacing, to the casting decisions, “Lady Bird” never misses a beat.

Set in an early-2000s Sacramento, CA, the film follows Christine during a senior year of high school befitting her character — a whirlwind, dizzy with emotion and prone to impulsive deviations. Gerwig does an exceptional job detailing the year, at times flying madly from one high or low point to the next, only to slow down at each moment to unpack the sensory intricacies of a school play, a dance, or a botched (and ultimately redeemed) prom night. Gerwig also demonstrates a phenomenal eye for understanding how to color in a movie along its margins: One scene involving communion wafers is a particularly inspired showcase of her subtly human touch.

Film critics love to deliberate over the ability of a movie or script to move beyond basic caricatures. We desire that films illustrate more complex and profound human subjectivities. It’s a classic critic’s trope. But we return to that trope for a reason — the successful execution of that ideal is one of cinema’s most triumphant qualities. “Lady Bird” has it in spades. The film expresses a remarkable generosity toward its subjects. Even peripheral characters are given space to articulate a range of humanities. It helps that those parts are driven by strong casting choices that mix veterans like Lois Smith and Tracy Letts with burgeoning stars like Lucas Hedges and Timothée Chalamet.

But “Lady Bird” is built on the performance of Ronan, who beautifully captures the irreverent wit and vivacity of Christine— though she’d really prefer you call her Lady Bird — and Metcalf as her world-weary and tough-loving mother. After Christine struggles with a classic and heartbreaking coming-of-age moment, mother and daughter reenact their Sunday tradition of visiting for-sale high-end houses that they could never afford. Theirs is a thoroughly middle-class family, and to see how the pair live out the fantasy of mobility — and how their financial reality has shaped their relationship — is both tragic and deeply humanizing for both characters. It’s the film’s most quiet and touching scene. Gerwig neither judges nor shies away from portraying the damage Christine and her mother do to one another, ultimately reminding us that their relationship is founded upon an intensely tender love that they often struggle to express.