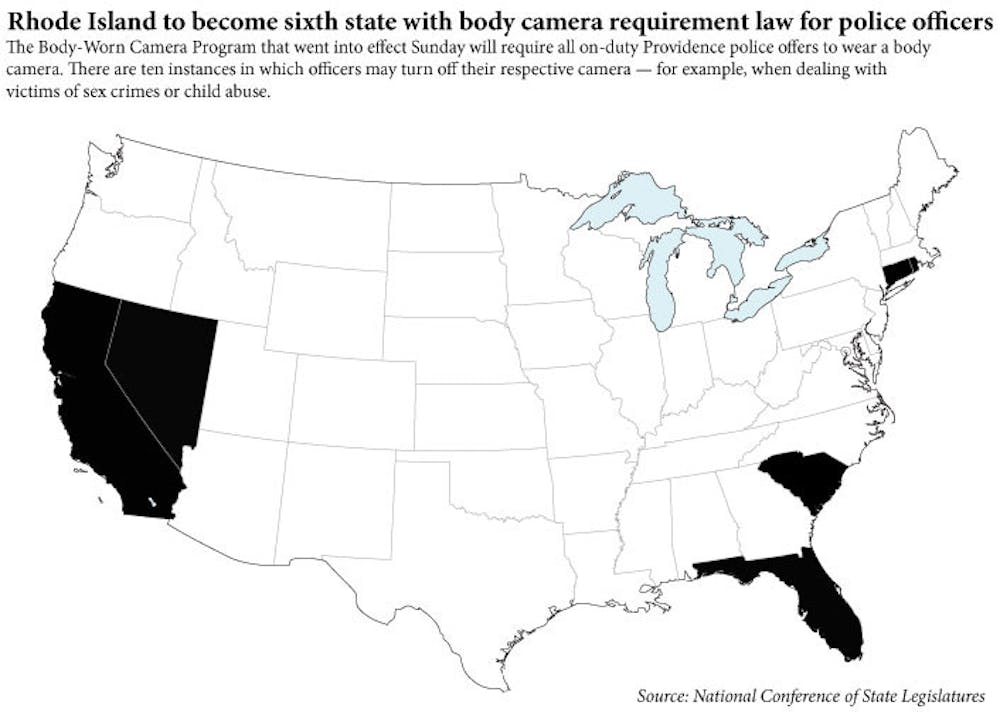

The Body-Worn Camera Program, which will require all on-duty Providence patrol officers to wear body cameras, went into effect Sunday.

An earlier form of the General Order was first introduced by the Providence Police Department Administrative Bureau in 2015, and an eight-week pilot program followed in the summer of 2016, according to Lt. Joe Donnelly.

“Different officers took (the body cameras) just to see how they would like them,” Donnelly said. “Most (of) the officers felt comfortable.”

Cameras from two different BWC companies, Axon and Vie-Vu, were tried out during the pilot period, and the Axon’s Body 2 Camera was ultimately selected. The Providence City Finance Committee and the full council approved the proposition, which also received commentary from other groups and individuals. This allowed for the cameras — along with 250 Tasers — to be purchased through a federal grant. Once the grant expires, the city’s Department of Public Safety will pay any associated costs itself.

“The body cameras are going to be an excellent tool for the Providence Police Department,” said Councilman of Ward 6 and Deputy Majority Leader Michael Correia. “If an officer is being accused of using excessive force or deadly force or is verbally abusive to somebody, well, now we have it on tape,” he said, adding that camera can protect police officers as well if they face a false allegation.

Each acting patrol officer will wear the square-shaped camera on the center of his chest, in plain view of the public, and turn it on during “all enforcement encounters where there is at least reasonable suspicion that a person has committed, is committing, or may be involved in criminal activity,” according to the General Order.

The cameras feature a manual on and off switch, and the policy cites 10 specific instances when the camera should be turned off. These include instances where the officer is dealing with victims of sex crimes or child abuse or when entering places where a reasonable expectation of privacy exists.

“The cameras are assigned to our officers just as their other equipment is,” said Public Information Officer for the Department Public Safety Lindsay Lague. “They will be required to take the camera home, as they do their radio, and place it in the docking station and video will automatically be uploaded.”

The footage is uploaded to a cloud-storage system, Evidence.com. Public record requests by members of the public wishing to view the footage are reviewed within the parameters of the Rhode Island Access to Public Records Act. But some groups, such as the Rhode Island American Civil Liberties Union, are concerned with this procedure.

“The problem with the APRA is that it … lists 10 or 15 things that are exceptions for anything that the state police has,” said Policy Associate of the R.I. ACLU Marcela Betancur. “That makes it a little harder for the public … to have access to some of this information.”

The R.I. ACLU is expected to send its formal edits to the Providence Police Department by the end of the week but maintains that the body cameras are “definitely a step forward,” Betancur said.

But some groups questioned the effectiveness of body cameras in curbing issues institutionalized in policing.

“We saw Rodney King get beaten up in ’92 on camera and the perpetrator still got away. … We’ve seen black people being shot and murdered on camera and nothing’s really been done, even though you can definitely see the killers,” said Vanessa Flores-Maldonado, organizer of the Providence Community Safety Act. “We’re not really counting on this to be something that helps solve police brutality and harassment. … We don’t believe body cameras will do much to curve racial profiling. And if it does, great, perfect, we’d love to be proven wrong.”

Officers will be trained to operate the cameras and understand its policy in a 3-day training session, according to Donnelly. The department is expected to be fully equipped within eight to 12 weeks.