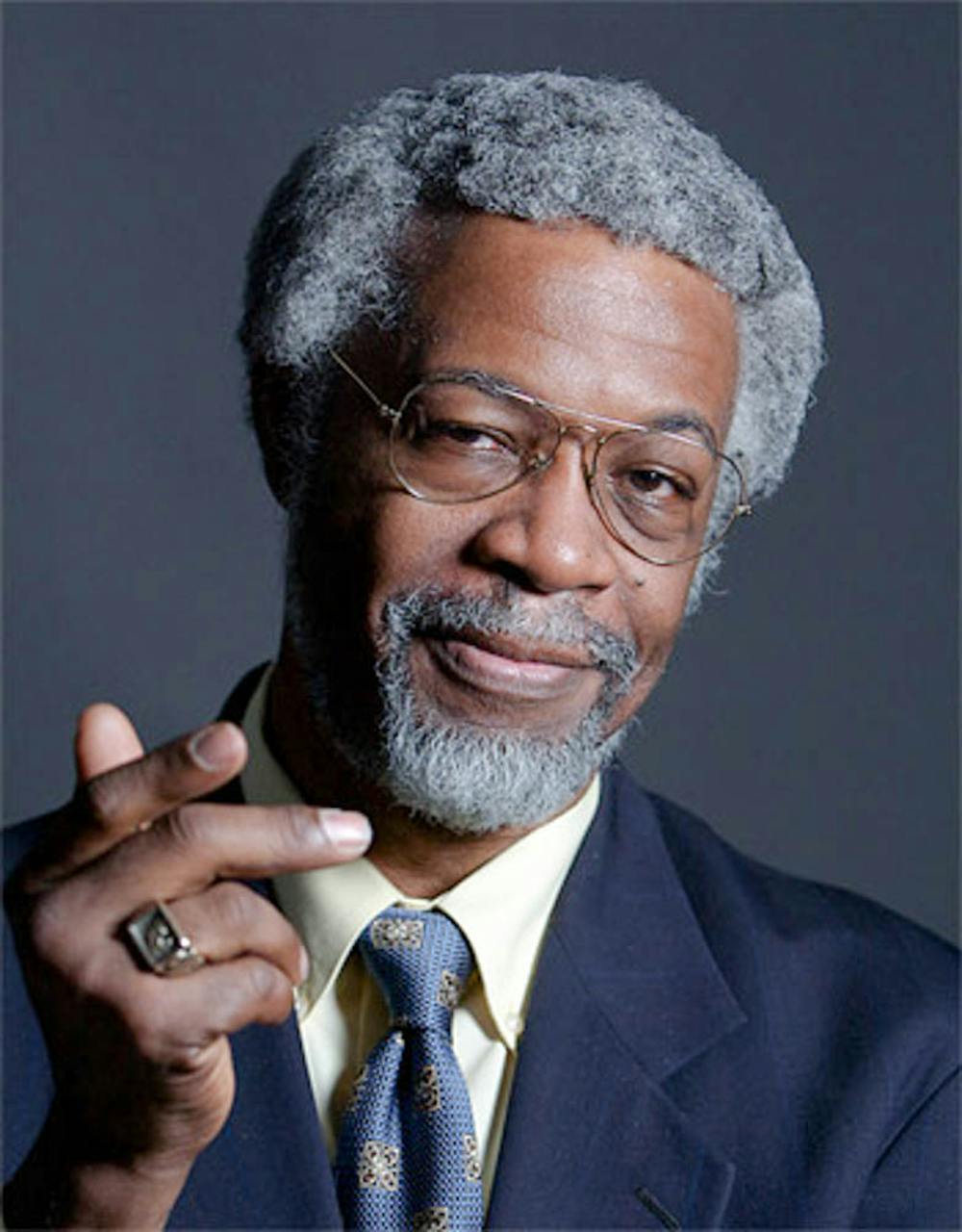

World-recognized theoretical physicist Sylvester Gates, better known as Jim Gates, started at Brown this year as the Ford Foundation Professor of Physics. Gates, who served on President Obama’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, studies supersymmetry, supergravity and superstring theory. More recently, he started working in forensic science. In 1998, he became the first African-American to hold an endowed chair in physics at a major U.S. research university, the University of Maryland in College Park, and was also the first African American theoretical physicist to receive a National Medal of Science and be elected to the National Academy of Sciences.

The Herald spoke with Gates about his work in forensic science and error-detecting codes, his role models and today’s skepticism surrounding science.

Herald: Could you explain your work in forensic science, and what drew you to that area?

Gates: Most people who have watched TV for the last decade or so have seen programs like CSI, which portray forensic science as extraordinarily scientific and effective at solving crimes. The reality falls far short from what you see in Hollywood and the media. In fact, the 2009 study report, “Strengthening Forensic Science in the United States: A Path Forward,” pointed out that a large number of the forensic disciplines, which often have people testify in court, lack a strong scientific basis for showing that what they present as science is reliable. Since 2009, there’s been a slow evolution. As a scientist external to the discipline, I have no vested interest in the outcome, one way or another. Working with groups (such as the National Commission on Forensic Science and the Organization of Scientific Area Committees for Forensic Science), we are slowly putting in policies to move forensic science as a practice to be more based on actual scientific methods that can be reliable and useful.

What kind of “more” scientific methods are you referring to?

Let me use the example of bite marks. People have made claims that you can identify individuals from bite marks they have left on a body. The Obama PCAST, which I was part of, looked at reports of forensic science and pointed out that there is basically no scientific evidence that bite marks can lead to identification of a specific individual.

What research do you hope to pursue going forward and why do you think it’s important?

A number of people are familiar with a TV production called “The Big Bang Theory,” which talks about string theory. Well, I am one of the people who actually works on this topic, and I have done so for all of my professional life. There are unresolved questions — in fact, string theory itself is incomplete as a scientific theory. For the last decade or so, I’ve been pursuing some unusual mathematical leads on how we can make it more complete. These leads have led to really strange results. One of the strangest that we have found is that many of the equations that we have about string theory are error-correcting codes. These are normally found in computer science, so why should the laws of nature involve this?

It seems like a lot of your work has been interdisciplinary — why do you choose to work at the intersection of conventional fields?

It is really only in this final push in my career that I have become more interdisciplinary. In my field (of theoretical physics), there is a problem that has not be solved in over 40 years. In the latter half of the ’90s, I decided that I wanted to go back and look at this problem and why it hadn’t been solved. Part of the reason the problem had not been solved is that everyone trying to solve it was using the same approach. I started developing some new ways of thinking about the problem (involving mathematics), and that’s what led to the discovery that certain equations have error-correcting codes in them. The old ways of thinking about it have failed, so I’m trying to at least make progress and move in an interdisciplinary direction.

Are there people that you’ve found particularly inspiring in your career?

For a long time in my life, I did not understand the term “role model.” And then I realized that the reason I didn’t understand it was because I had so many (role models) that I had never thought of it! My personal role model was my father, who was an incredible man — not a scientist, but a soldier and veteran of World War II. A couple of outstanding ones from my youth were my geometry teacher, my high school physics teacher and my first physics teacher at the (Massachusetts Institute of Technology). The list goes on and on, and today it includes an array of people far too many to name. One of the people that I have had as a real hero was Dr. John Holdren, who was Obama’s science advisor. I had many interactions with him over the course of eight years with the Obama administration.

My hero maximus is Albert Einstein. Many people have heard about Albert Einstein — he was one of the most brilliant scientists. But many people do not know that in addition to science, he was just an incredible human being. In 2005, there was a celebration of his work because it was in 1905 that he produced the first set of his dazzling results. That year, I had to speak more than 40 times on five continents about Albert Einstein, so I basically bought a library so I could knowledgeably speak on him. I knew about his physics, but I learned about him as a person during that year. What I found most incredible was that Albert Einstein was one of the most forceful speakers against racism in the United States during the ’50s. He made forceful statements about the racism and the injustices that were inflicted upon African-Americans in this country. There’s a book called “Einstein on Race and Racism,” where anyone who wishes to learn about this aspect of his life can do so. He was also just someone who tried to help people in general, and this is something I didn’t understand about Albert Einstein until I had to speak on him.

In physics and the science community in general, how do you think that the academic climate has changed for members of historically underrepresented groups?

The unfortunate truth is: not very much has changed. There’s a general idea that things have vastly improved, but recently there was a story in the New York Times that showed that the percentage of African-Americans in college has basically been the same for the last 30 years. People think that there has been rapid progress, but if you look at the numbers, that’s just not true. For my community, there has been very little change.

How do you hope to see it change going forward?

I’d like to see a society where fairness is more widely distributed and where outcomes are not dependent upon one’s economic or geographical origins.

In your work communicating science to the public, what do you hope to leave people with? Are there any common conceptions you’d like to correct or influence?

There are many misconceptions about science in the public. I’ve spoken on very specific things — for example, the detection of gravitational waves. When I am called upon to speak to the public about specific scientific discoveries, I try to do so in a way so that it becomes understandable, and also in a way that it becomes understandable as part of a human activity. When someone writes a great novel or piece of music for the public, a lot of people get enthusiastic and understand that there’s a creative process at work there. It’s the same thing with science. It’s a very human endeavor, and it’s not something that only geniuses do, which is one of the biggest misconceptions. I try to communicate these things when I speak about science. It’s a large-scale activity that’s extraordinarily important for our species. We face changes like climate change, and the only thing that’s protecting us is our technology, and our technology comes straight from science.

In this current era of fake news and distrust of science, how has your role as a researcher changed and how have you approached skepticism?

First off, skepticism is one of the bases of science, which most people don’t seem to understand. Scientists don’t just fall in love with our ideas. Science is one of the most argumentative things. Skepticism actually drives the development of science, because you’re always skeptical of your colleagues’ ideas. On the other hand, the kind of skepticism that we see playing out in the large social realm of our society right now is extraordinarily concerning. It kind of implies that everyone’s opinion is equal, and that’s just not true. People who are not informed do not have good opinions.

— This interview has been edited for clarity and length.