[gallery ids="2826316,2826317,2826318,2826319,2826320"]

Two months after the Corporation, the University’s highest governing body, authorized the construction of a new performing arts center in the middle of campus, the undergraduate student body is split on whether the center should be built in its proposed location along the Walk between main campus and Pembroke, according to The Herald’s undergraduate spring 2017 poll. The new center will require the demolition of several campus spaces.

The arts center would establish a hub for music, dance, theater and multimedia art, which the University currently lacks and has considered a priority since 1974, according to a Feb. 11 community-wide email from President Christina Paxson P’19. According to a University press release, constructing the center would require demolishing a “parking lot, three residential structures and two academic buildings” — including the Urban Environmental Laboratory, a center for environmental studies and activism on campus.

Tension between two communities

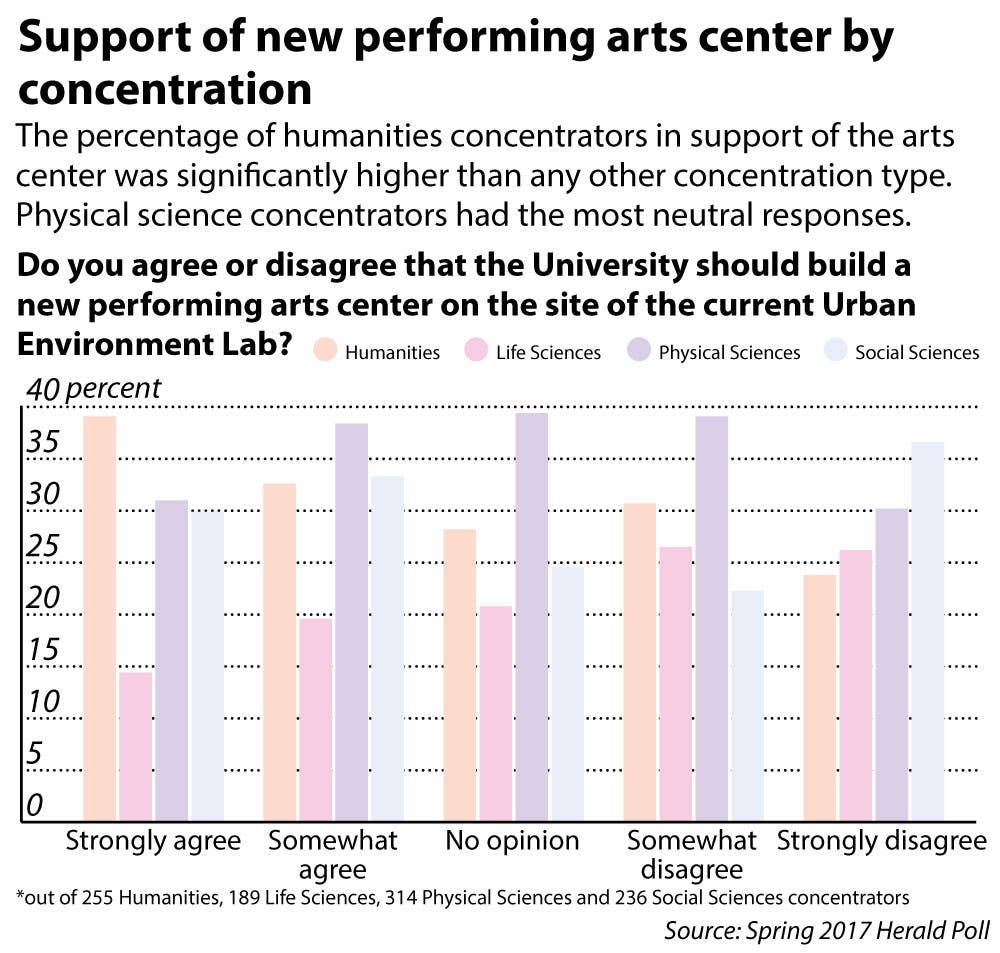

About 40 percent of students strongly or somewhat disagree that the University should build a new performing arts center on the site of the UEL, according to the poll. About 34 percent reported that they have no opinion, while just over one quarter of students are somewhat or strongly supportive of the project.

The narrowness of these margins reveals the thorniness of a decision that implicates two critical spaces on campus — the home of the environmentally-minded community and a potential new home of the music community.

Individuals in both constituencies wish it weren’t so. “They are trading one community center for another,” said Katie Rademacher ’19, the current president of the Brown University Orchestra. “In order for the performing arts people to have a place where we can all come together and we can all create together, … we have to get rid of that kind of space for environmental science people. That doesn’t sit right with me.”

The proposed center will include a concert hall that will be large enough to accommodate an orchestra and seat hundreds of students and community members — the type of space the University lacks compared to peer institutions, said Frank Jodry, senior lecturer in music and director of choral activities.

The value of the UEL

For students who will be directly affected by the destruction of the UEL, the cost-benefit analysis can’t be a quantitative question, said Brendan George ’18, an environmental studies concentrator who is also a member of the Jabberwocks a capella group and the IMPROVidence comedy group.

But even those students who don’t interact with the UEL on a daily basis benefit from its presence, said Logan Dreher ’19, an environmental studies concentrator. Not only are many groups housed at the UEL — such as Bikes at Brown — but it also provides space for collaboration between students and organizations like Farm Fresh Rhode Island and the African Alliance, a community organization for African refugees.

“Because so many things have started in the UEL, and it is this space for collaboration, its impacts go so far beyond the people who use it,” Dreher said. “It creates a space for people to bring sustainability to other places.”

The UEL also represents a history of student commitment to sustainability and a growing commitment to environmental justice: The UEL is a historic carriage house that was renovated in 1981 and later inhabited by students who wanted a space reflecting their values.

“Destroying a community gathering place in favor of a more imposing and less accessible building (is) not in line with the principles of environmental justice,” Dreher said. “It goes along with Brown’s history of taking away from the Providence community and taking away historic buildings to create new ones.”

The UEL also serves as a center of campus life for students involved in environmental coursework and extracurricular activities. It produces a tightly knit community that attracts many students to concentrate in environmental studies and science, said Angelica Arellano ’18.

“I was trying to think of something I haven’t done in the UEL — I’ve showered there, I’ve napped there, I’ve cried there,” Dreher said

“If you think about the nutrient cycle, this is our built environment of a nutrient cycle,” George said. “You have healthy minds coming in, working together and creating great new ideas from other healthy minds.”

The UEL is to the environmental community what the proposed performing arts center will be to the music community: a space for students, faculty and staff members to interact in formal and organic settings, as well as an accessible center connecting Brown to the greater Providence community.

Needs of performing artists

“Brown should think big and think not only about Brown University’s needs but also the needs of the city,” Jodry said. “The facility can make summer arts festivals happen … to enliven the life of the city.”

Many students involved in performing arts on campus agree that it is necessary to have a proper, high-quality facility to reflect the needs of the extensive art community.

“We have some very high-quality performances in music going on that are not in a place that is suitable for a performance of that caliber,” said Devon Carter ’19, a music concentrator, who is on the board of Brown Opera Productions.

“The space is actually letting down the art,” Carter said. “Take Granoff, for example. There are very few ensembles that would go well in that space. … The stage is too small for a large group, and the house is too big for a small group,” he added.

Theater arts groups currently host performances in locations all over campus, but student music groups have a very limited number of facilities to use.

The orchestra regularly rehearses in Alumnae Hall and performs in Sayles Hall, which is the only place large enough for a music group of that size, said Maxwell Naftol ’19, a music concentrator who has performed with the orchestra since his freshman fall.

“There’s definitely a lot to be improved upon in terms of sound and acoustic quality,” Naftol said. At every rehearsal, students have to spend 30 minutes before and after setting up and breaking down equipment; for concerts, all equipment must be transported via moving truck to Sayles Hall, he said.

“The most important thing is that all of the things that exist in the UEL right now — all of those departments and offices, those programs — have another space when the UEL is demolished,” said Cora Wiese Moore ’19, an environmental engineering concentrator, an active member of the chorus and a harpist. “I personally have more of an incentive to support a performing arts center,” she added. She said she would prefer that the music spaces on campus be centralized at the new center.

“Personally, with the harp situation, it’s awful,” Moore said. She currently practices in the wooden shed in Alumnae Hall, where there is no soundproofing, and stores her instrument in the same space, which is not designed for storage.

Cameron Neath ’18, a theater arts concentrator, is currently directing a production in downtown Providence. She said that Brown’s own facilities for performing arts are “incredibly limited.” Student groups are not allowed to use the facilities monopolized by the theater department, so many shows go on at Production Workshop or in various rooms around campus. But space is limited even for the theater department, which has the Leeds and Stuart theatres. Senior students have to do a capstone project, yet “the department does not provide those seniors with any space to do that performance,” she said.

Possible alternatives

Naftol was very surprised by the poll results. “I really don’t want it to be framed like music department or performing arts in general is trying to be greedy and take this land, because I don’t think that was anyone’s intention,” he said, adding that “they’re both important, but it’ll be easier to relocate the smaller one of the two, which is the UEL.”

One possible reconciliation would be to locate the performing arts center off College Hill, Jodry said, adding he would like to see the center constructed at the current site of the School of Professional Studies in the Jewelry District — the best piece of real estate the University owns because of its riverfront location.

Not only is parking limited on campus, but the proposed site sits atop the Thayer Street bus tunnel, which means hundreds of thousands of dollars would have to be invested in noise mitigation, Jodry said. Instead, he envisions an “architecturally significant” gathering place in the Jewelry District that hosts professional artists traveling the New York-Boston circuit, serves as an anchor for the community by putting on events like music festivals and offers a home base for students and faculty members involved in the performing arts, he said.

“There is a hole that needs to be filled,” Rademacher said. “But I don’t think you fill a hole by taking from another area and putting it there.”