Listening to “Triplicate,” Bob Dylan’s latest album released Mar. 3, it’s hard to imagine the Dylan who played at Brown in 1964.

Though most of the tunes are covers of popular sentimental songs from the early 20th century, Dylan disowned his most recent release’s purported nostalgia in an interview with Bill Flanagan. “It’s not taking a trip down memory lane or longing and yearning for the good old days or fond memories of what’s no more,” he told Flanagan.

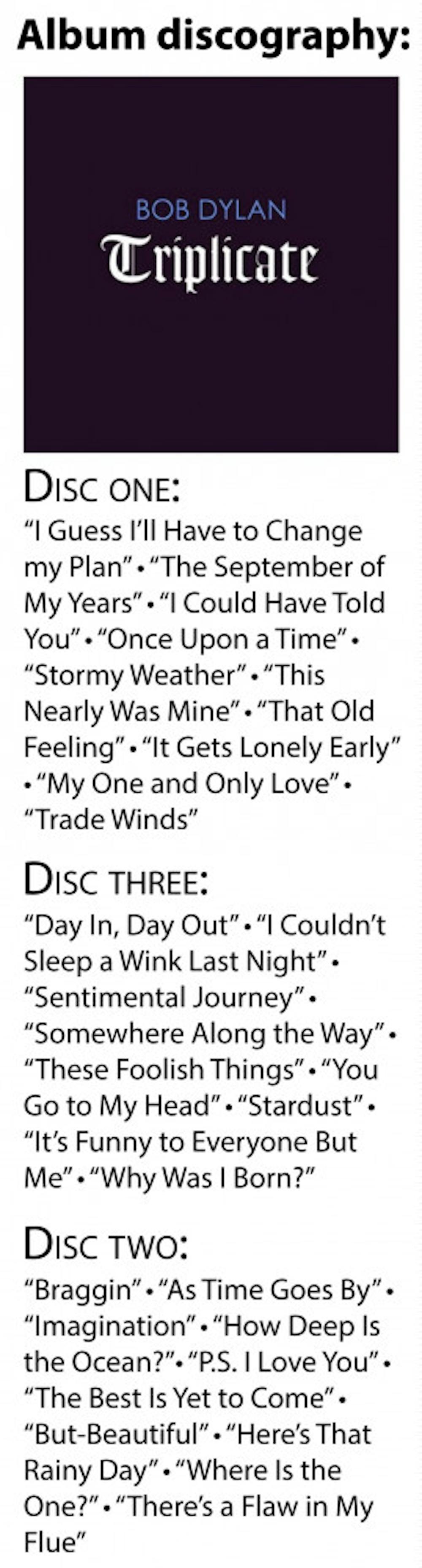

That’s a challenging claim to support. Dylan still defines the length of his albums by how much good quality sound can fit on a record, not a CD, dividing his album into three interrelated 32 minute albums — imagine 16-minute sides of a vinyl. The idea to make a three-part reflective series echoes an earlier Frank Sinatra album, “Trilogy: Past, Present, Future,” released in 1980. Furthermore, the songs on the album are an aggregate of songs made famous by twentieth century standbys such as Rodgers and Hammerstein, John Coltrane and Frank Sinatra.

Perhaps the listener interprets the album’s 30 songs as nostalgic because the feelings conveyed in the lyrics and melodies have been delved into for so many years — but that’s because they’re grounded. They’re the “essence of life,” according to Dylan. And maybe he knows — he’s been around for a while now.

In fact, songs like “That Old Feeling” and “Sentimental Journey” outdate the veteran songwriter himself, emerging during and even before his very early childhood in Duluth, Minnesota when he still went by Robert Zimmerman. Actually, the album might have been a more obvious soundtrack for the Depression and World War II eras than for today, a time when, Dylan says, “songs are so institutionalized that you don’t realize it.”

Admittedly, Dylan’s recent career is not flawless. There is undoubtedly something a little cringe-worthy in hearing the same spirited pioneer from the 1960s musical revolution sing fragmented Christmas songs in a tired voice like he does in his 2009 release “Christmas in the Heart.” But the album’s searing and somber rendition of “Silver Bells” acts as a prelude to what Dylan reveals in “Triplicate.” Sure, it’s no “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” but that type of track could not work today. Dylan’s perspective has adapted, the music world has evolved and the political atmosphere has changed. Maybe this is why listeners feel their own kind of post-1970 nostalgia listening to the new album.

But it’s not the 1960s, Dylan’s out of Woodstock and there will never be another “Highway 61 Revisited.” Instead, the “Triplicate” listener encounters a new sober, sentimental Dylan with a certain well-deserved gravity. And it’s this heaviness, this entire lifetime, that, layered over “Nashville Skyline” and “Blonde on Blonde,” accomplishes something entirely new in its severe honesty. The songs on “Triplicate” aren’t pop songs — they’re worn-out, they aren’t flashy and they aren’t radio-ready. The tracks challenge the glossy, Nobel-Prize winning, chart-topping career of one of the most influential musicians in history.

When Dylan covers these classics, he performs the equivalent act of what modern musicians have done over and over to his own songs. The songs Dylan plays on “Triplicate” are the “Make You Feel My Love” and the “Wagon Wheel” of World War II. As these early twentieth-century hits begin to lose their traction, an opportunity exists to revive music that drives at what it means to feel anything at all in the most unabashed, and, at times, painful way. It’s not nostalgic to reach for the feeling that ended in the era of jazz and Frank Sinatra — playing these songs is an opportunity to demonstrate universal experiences, which are still very much a part of life today. And who better to take on this challenge than Dylan, the man who wrote the next generation’s standbys?