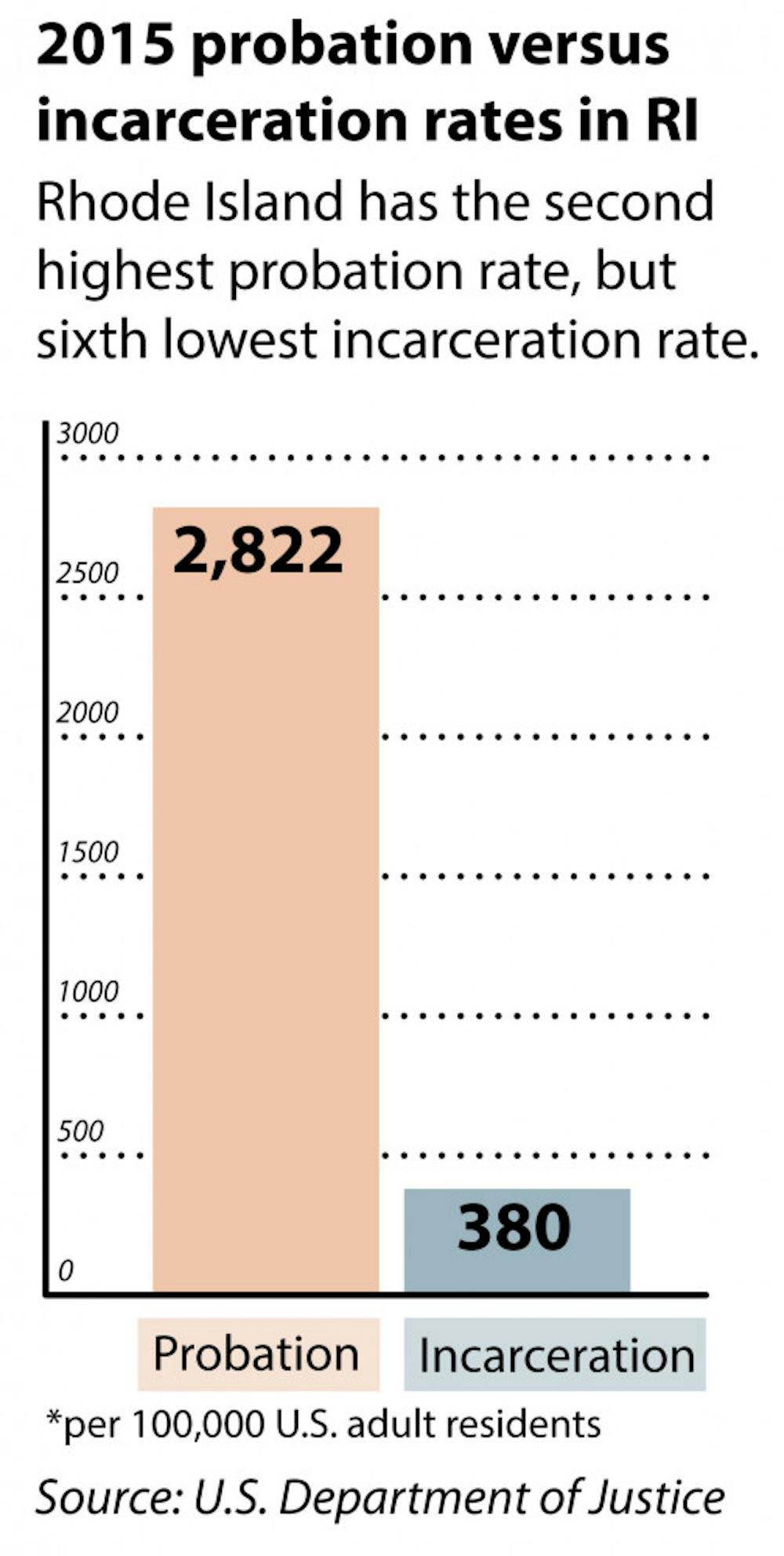

The Rhode Island Senate passed a package of reforms Feb. 2 with aims to improve the state’s probation and parole system, one of the country’s worst. While Rhode Island’s incarceration rate remains one of the lowest in the United States, its probation rate is the second highest, with 24,000 people on probation every year, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

While previous efforts to pass similar bills have failed, the new reforms introduced by State Sen. Michael McCaffrey, D-Warwick, include bills to create a batterer’s intervention program and emphasize mental health treatment as an alternative to incarceration.

Rhode Island’s large probation numbers are in part due to long probation sentences, which can last up to 30 years under state law. Other states typically dole out probation sentences from one to three years, according to Barry Weiner, associate director of rehabilitative services at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections.

“We have too many people on probation for too long periods of time. Our laws and our policies are antiquated,” said Shelley Cortese, associate director of community corrections at the Department of Corrections.

The DOC is “fully supportive” of the bills, said Barry Weiner, the assistant director of the DOC. Shelley Cortese, the associate director of community corrections at the Department of Corrections, added that the reforms would strengthen the DOC’s role in working with offenders on probation.

The current long probation sentences assigned are unnecessary and can have negative effects on the lives of offenders, said Steven Brown, executive director of the Rhode Island ACLU. “It imposes significant constraints on their liberty and holds over their heads the threat of imprisonment if they do the smallest thing wrong,” he said.

Reforms around probation have recently gathered traction in the state. Prior to the passing of Rule 35C last year by the Rhode Island Superior Court, offenders on probation were not allowed to end their probation early, said Lisa Blanchette Chamoro, assistant parole and probation administrator for the Department of Corrections.

Those re-offending and violating probation may be incarcerated for either a new charge or for technical reasons, including violations like failure to appear for a scheduled visit with probation officers or missing curfew, Chamoro said.

Thirty-one percent of offenders return to prison due to probation violations, according to the RI DOC Fiscal Year 2015 Annual Population Report. As a result of these longer sentences, “people who might be a lower-risk pick up a new offence and end up in the violation status,” Cortese said.

Despite this, representatives of the DOC assert that probation is a better alternative to incarceration. “There’s a lot of research that says prison makes people worse,” Weiner said. “The longer offenders are away from the community, the more difficult it is to re-integrate them thereafter and be productive,” he added.

“People simply don’t need to be locked up or kept on probation for the lengthy periods of time that they currently are,” Brown said, adding that “prevention or mental health services would be much more effective in addressing crime.”

“There’s also an economic impact of not incarcerating somebody,” Weiner said, adding that incarceration prevents people from supporting their families and paying taxes. “You could put eight people on probation for every person that’s incarcerated.”

Probation costs less than incarceration, accounting for only 8 percent of the DOC’s budget, while the majority of funding is allocated to the Adult Correctional Institutions — the DOC’s main prison complex, Weiner said.

The package has not been universally well-received, however, and House Speaker Nicholas Mattielo, D-Cranston, has come out against the reforms in the past, calling identical bills “soft on crime.” Brown rejected such a conclusion and said that the reforms’ impact on crime will likely be “negligible.”

Contrary to its high probation rate, Rhode Island has the sixth-lowest rate of incarceration in the country, but Brown said that this is partially owed to the state’s small population and lack of big-city crime.

To keep incarceration, probation and recidivism rates low, Professor of History Amy Remensnyder said that an effort must be made to invest in schools and programs to help people out of poverty, combat racism and get rid of mandatory minimum sentencing.

“Having all of those things in mind can help lower incarceration rates back to what (they are) for other industrialized Western nations,” Remensynder said. “We have a very punitive attitude towards people who are perceived to have committed wrongdoings.”