Over spring break, many students will return home to their families, but for Orwa Mohammad ’20, that option isn’t so simple. Home, for him, is Syria.

As a Syrian citizen, Mohammad must complete a compulsory military service for two years. Next month, he will be required to return to Syria to serve, but he can postpone his enlistment by proving his university enrollment to the Syrian embassy. However, that requires traveling to the nearest embassy — which is located in Vancouver, Canada.

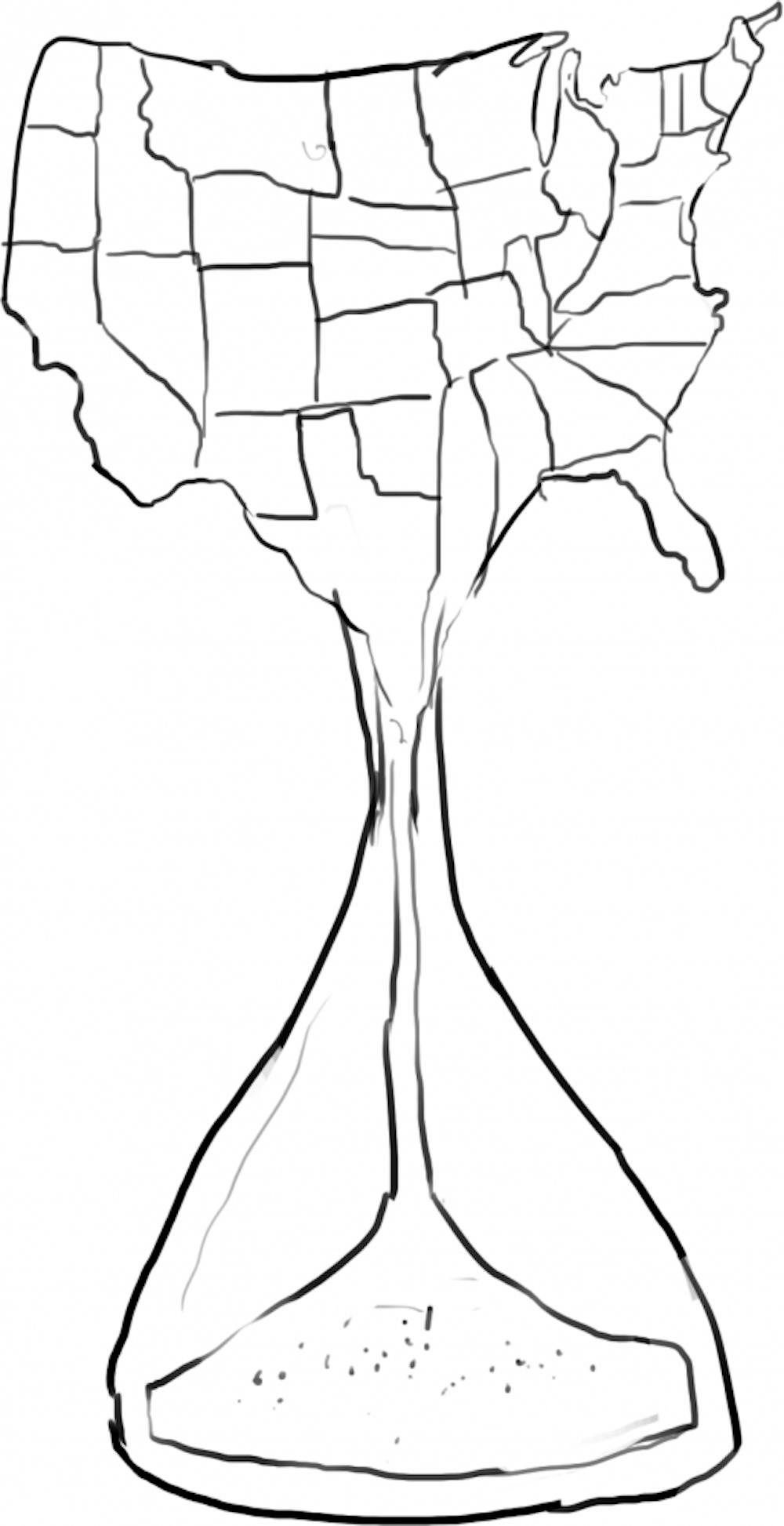

Though Trump’s revised immigration ban was placed on hold by federal judges from Hawaii and Maryland, the University still advises international students like Mohammad not to leave the United States, according to the office of global engagement. This has created problems for students, like Mohammad, who must make a complicated decision about their futures in the United States.

Though the Syrian government cannot force Mohammad to serve, the embassy can refuse to renew his passport, which expires in August 2018, if he does not fulfill his duties.

“I have no clue where I’m going to be, what my legal status is going to be, when (I will) be able to see my family, when … I’m actually going … to (return) home,” Mohammad said.

Changes since Trump

Mohammad said it took some time for him to realize how much would change after Trump succeeded in winning the presidential election. “It didn’t feel like there was going to be that much of a drastic change until the (first immigration) ban actually came.”

Though the second immigration ban does not target international students with valid visas, border patrol officials still have wide latitude in placing valid visas under administrative processing, The Herald previously reported. “The risk is if the person leaves and the order is then reinstated, they could face a certain instance where they will not be let back into the United States,” said Michael Wildes, former federal prosecutor with the United States Attorney’s Office in Brooklyn.

“It’s never a guarantee for a student traveling that they’ll be readmitted anyways,” he added. “They’re in a catch-22 position where they’re damned if they go and damned if they stay.”

An unlikely path to Brown

Mohammad grew up in port city of Tartus, located on the country’s Mediterranean Coast.

“There was a certain sort of community feel,” he said. “I knew I could rely on people.”

But the city consists of “mostly government supporters,” he added. “They’ve been empowered by Assad.” This support has shielded the city from most of the chaos of the ongoing civil war, but in 2014, Mohammad began to explore the option of continuing his education outside Syria as the prospects of living a “good life” seemed increasingly unlikely. While the civil war resulted in only “mild” changes in Tartus, Mohammad said the country’s inflation and low wages forced his father to seek work in Abu Dhabi. That year, Mohammad won a scholarship to attend United World College Maastricht in the Netherlands.

While attending UWC Maastricht, Mohammad said he started to consider college in the United States.

“Back then, the U.S. seemed like a great place to live in — great universities — and they give scholarships so why not?” he added.

Mohammad got into his top choice school: Brown. “I came here thinking that I would be able to go back in the summer to see family,” he said. “That’s not happening now.”

“Maybe if I had applied this year instead of last year, I would’ve applied to Canada,” he added.

Strained relationships

Mohammad also said the ban has taken a toll on his relationships with his parents and younger sister who live in Abu Dhabi. “When (my parents) first heard about (the ban), they refused to believe … it could apply to students.”

Mohammad said his family tries to hide their reactions from him.

Mohammad can stay in the United States for four years without any visa issues — but in those four critical years, he worries he won’t be able to watch his ten year old sister grow up.

“I didn’t want to … go back to see her and she’ll look at me and be like, ‘Who are you? You’re the guy who left me when I was eight years old and now you’re coming back like nothing has happened.’”

“That’s when (the uncertainty) actually hit me, and since then it’s always been in the back of my mind,” he added.

While his wide circle of international friends supports him at Brown, Mohammad said that he often struggles to let others know he’s not okay.

“It takes time to trust someone,” he said. “It takes a lot of trust to tell someone, ‘I’m not doing that good, I’m not fine.’”

Mohammad has noticed that students from Brown and Europe react differently to his identity as a Syrian.

Brown students “aren’t curious,” Mohammad said, adding that, in Europe, he got more questions about the war in his homeland than he does here.

“I appreciate the questions,” Mohammad said. To not ask questions is “counterproductive,” he added. “You need to know. You are the people of the United States, and the people you elect will not only rule the United States but they will also decide the future of the world.”