Updated on Mar. 22 at 12:57 p.m.

The debate over graduate student unionization at the University starts a new chapter as Stand Up for Graduate Student Employees — the main group pushing for unionization on campus — concluded voting on the labor union with which it will affiliate. The American Federation of Teachers was selected as the affiliated labor union, according to the results of the vote made public Tuesday night, wrote Joseph Skitka GS, a member of SUGSE and its affiliation working group, in a follow-up email to The Herald. All graduate students were eligible to vote between the AFT and the United Automobile, Aerospace and Agricultural Implement Workers of America, both of which would offer resources such as legal advice, access to lawyers and guidance in contract writing, according to Ian Harding GS, a member of SUGSE.

The AFT and UAW are similar in that they are both “large, international unions, and they both represent tens of thousands of graduate students and student workers across the country,” Skitka said. The two unions have differences, however, which lie in their approach to organizing. In order to form a recognized union of graduate students at the University, a plurality of the bargaining unit — PhD students currently serving in teaching and research assistant roles — must vote in favor of unionization. To secure 51 percent of the vote, a campaign for unionization must take place, which “will affect the whole campus,” Skitka said.

UAW “believe(s) that a graduate-led, grassroots canvassing structure is the best approach, and it may be a little slower of a process” because it relies more on graduate students being responsible for canvassing, Skitka said. While both unions would send staff members to campus in administrative, supportive and training roles, AFT would also send in staff members as a part of the unionization campaign to walk around campus and talk to students. This approach can move the process along faster, Skitka said.

AFT offers “a bit more freedom” by allowing “a local union to determine their own bylaws and structure, whereas UAW kind of provides a basic structure and bylaws for us in constitution,” Skitka said. He also pointed out the possibility that UAW would have the graduate student union at the University “join a local union with workers from other industries.”

Narrowing down to two unions “was a very thorough process where we wanted to exhaustively explore all the options,” Skitka said, adding that “it was really important to us to make students feel like they had the ultimate say in this matter.” SUGSE initially reached out to seven different unions based on which ones had existing relationships with graduate students, and the two ended up being viable options, he added.

While SUGSE has gained traction on campus, some oppose unionization because a number of graduate students may already feel content with their departments and their positions within them, according to the Graduate Student Council FAQ sheet related to unionization. What SUGSE is hoping to achieve through unionization is “a better quality of life for graduate students,” Harding said. “Not that our quality of life is necessarily bad, but without a legal, binding contract, it’s liable for change,” he added.

“If your department falls on hard times, or the University decides to fund some other project … you have no leg to stand on” without a contract, Harding said. He also pointed out that there are disparities between departments, and that by standing with other graduate students you can help your peers. For example, the minimum stipend is $24,870, but some departments pay more than that or have different policies for how that funding is dispensed, Harding said.

For Skitka, there is a “broad ideological argument” for why a union would benefit graduate students.

The nature of the administration is that they don’t interact with graduate students on a daily basis and that “their decisions and how they use their power will sometimes leave people behind,” Skitka said. “They will operate in such a way that will try to advance things they care about, like the standing of the University (or the) rankings of departments,” which don’t necessarily speak to the needs of graduate students.

“A natural way to resolve the issue of people being left behind is to share power among everyone who is affected by and contributes to the functioning of the University,” Skitka said.

Unionizing could also achieve wage increases, a more robust grievance procedure and a contract obligating the University to follow through on whatever the bargaining unit and the administration agree upon, Skitka said. Some students may not feel comfortable using the grievance procedures built into the University concerning issues pertaining to sexual assault, summer funding, being asked to serve as a teaching assistant for multiple courses or being able to afford health care for dependents, he added. Affiliating with a union and creating a contract could provide enforceable timelines for responding to concerns. In addition, students feeling overworked could notify the union, which “will send in a representative” on behalf of the student to raise the concern.

The 2004 decision of the National Labor Relations Board in Brown U. v. United Association of Automobile, Aerospace and Agricultural Implement Workers of America — which ruled that graduate students at private universities were not an appropriate unit for collective bargaining — was overturned this past August, clearing the way for unionization at private schools like Brown.

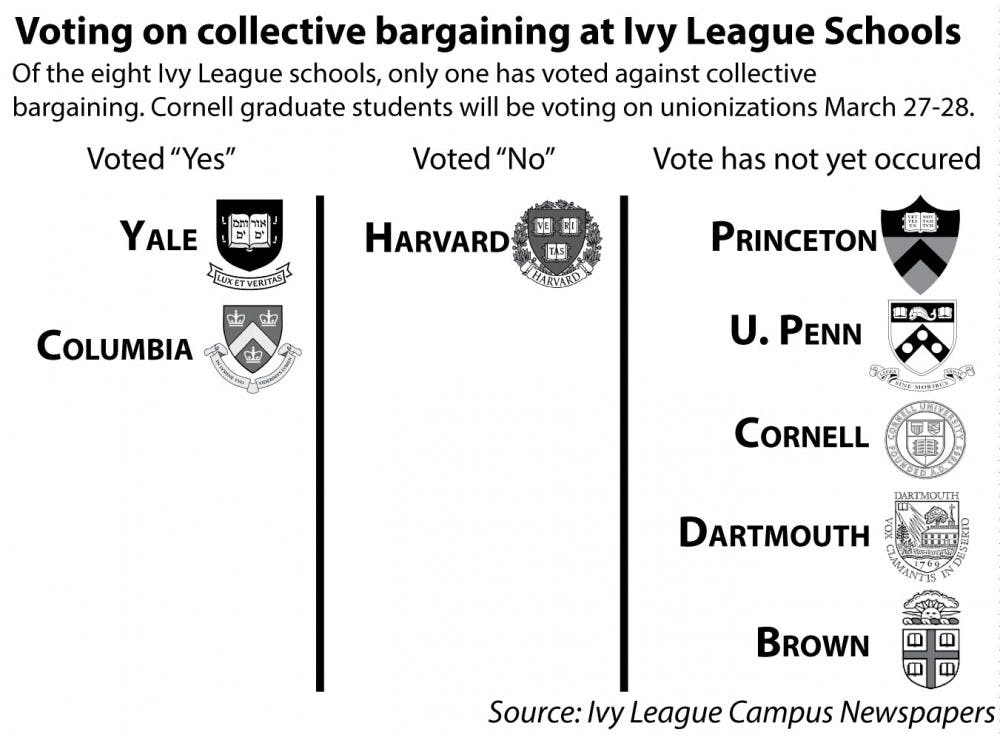

In the months since the overturn of the decision, graduate students across the country have taken steps toward unionization, most notably in the Ivy League, where votes on unionization have already occurred on multiple campuses. Votes on the right of student unions to collectively bargain for graduate students employed by their universities have already taken place at Columbia, Harvard and Yale with mixed results. A vote on unionization at Cornell will take place from March 27 to March 28.

Unionization “comes down to enabling effective collective action,” said Danielle Dirocco, executive director of the Graduate Assistants Union at the University of Rhode Island. “When push comes to shove, and we’re not getting paid well, we have the means to come together and apply pressure in an official way to our administration to ensure that our needs are being met,” she added. “And we’re able to do it in an amicable way.”

Because URI is a public university and not covered by the original Brown decision, graduate students at URI affiliated under the American Association of University Professors in 2002, negotiating their first contract around wages and insurance that year.

The concerns of graduate students at URI have continued to revolve around high student fees and low stipends, as well as limited on- and off-campus housing and parking passes, Dirocco said. A level one stipend for the first two years as a master’s student is $17,184 per year. With a maximum 20-hour work week, this amounts to a $23.87 hourly wage.

Graduate students at Brown are concerned with having to pay dues regardless of whether or not they want to join the union, according to the FAQ sheet. The average dues paid by UAW affiliates is 1.44 percent of their salary. Harding says that if a union is formed, they will work to negotiate for “a pay raise that covers dues so that we don’t see a difference.” Comparatively, URI graduate students are expected to pay $1,566 in annual fees, but can receive a 20 percent waiver if they hold a teaching or research “assistanceship” qualifying them for a stipend. According to Dirocco, even part-time graduate employees pay the full fee, as well as any graduate student who does not have an assistanceship, meaning they are not currently a teaching assistant or research assistant. Additionally, some departments offer acceptance to graduate students they cannot afford to support in an assistanceship role and therefore are only paid the hourly wage without their tuition being waived — something that is common for most PhD students.

A notable aspect of URI’s unionization was that the “president of the university said, ‘You guys need to unionize,’” Dirocco said, adding that as a whole, “we had strong encouragement from our administration to unionize.”

Such institutional support is a far cry from the reality faced by graduate students at many private universities, which have historically opposed unionization on their campuses. Before a judge reversed the Brown decision, the University, along with eight other private institutions, filed an amicus brief March 1, 2016 arguing that the NLRB should continue to consider research assistants and TAs as students, not employees.

While graduate students attempted to unionize in 2004, former Provost Robert Zimmer issued a statement that the “NLRB correctly recognizes that a graduate student’s experience is a mentoring relationship between faculty and students and is not a matter appropriate for collective bargaining.”

Despite its past opposition, the University has not indicated that it intends to push the issue any further. When the NLRB reversed the Brown decision in 2016, the “University made it clear that we would comply with the ruling,” wrote Dean of the Graduate School Andrew Campbell in an email to The Herald. “We acknowledged that it would be the decision of eligible graduate students as to whether or not unionization was right for them, and we affirmed our commitment to promoting an environment that supports open and informed discussion, free of intimidation by any party.”

Correction: A previous version of this article misstated that SUGSE members decided between which labor union the organization would affiliate. In fact, all graduate students were eligible to vote on which labor union SUGSE would affiliate with. The Herald regrets the error.