Illuminating the quotidian reality of a dynamically intellectual group, “Women of the Page: Convent Culture in the Early Modern Spanish World” showcases a collection of portraits, engravings, objects and manuscripts. The exhibition gives voice to devout, early modern Spanish and Latin American women who were often misrepresented as static and inexpressive.

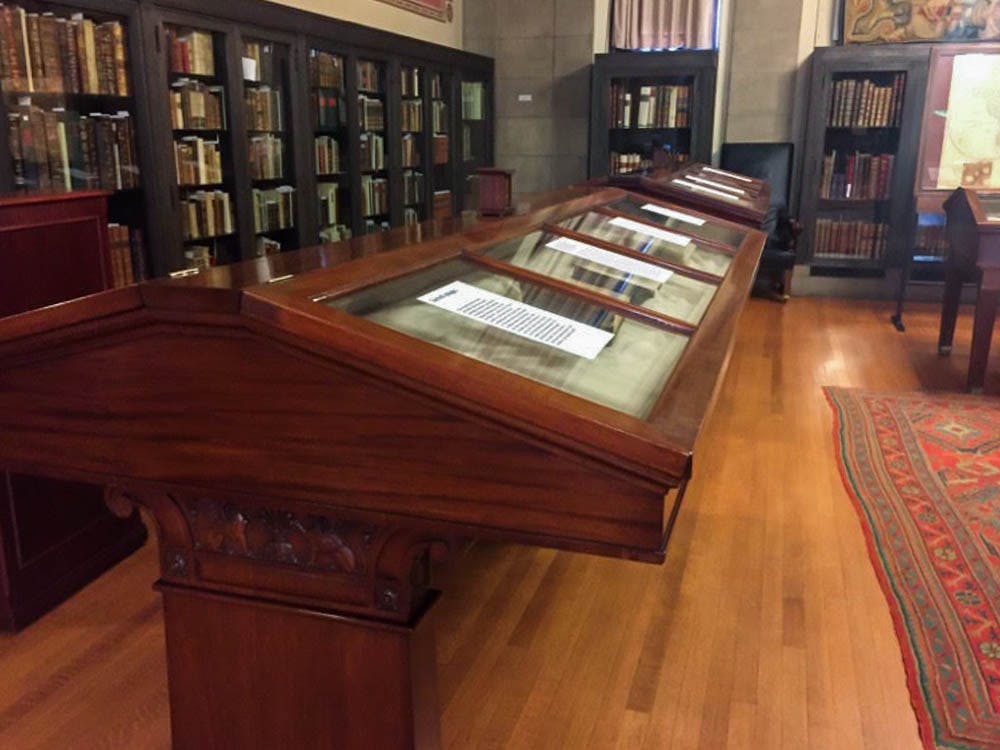

On display at the John Carter Brown Library, “Women of the Page” was curated by Tanya Tiffany, associate professor of art history at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and former JCB research fellow. The exhibit opened in early February with a roundtable discussion and will be on display through mid-April.

Tiffany’s work “brings together visual culture and the Hispanic world to reveal the spaces and roles women occupied in convent life,” said Neil Safier ’91, associate professor of history and director and of the JCB. The exhibition is “a great opportunity to peer into a world not only unknown to us but also to those who lived during the period it represents.”

Six display cases comprise the exhibition: “Representing Nuns,” “Journeys,” “Divine Love,” “Nourishing Body and Soul,” “Sacred Images” and “Wealth and Rank.” Each reflects elements of female empowerment and intellectualism characteristic of the convent environment.

One engraving, “The Hieronymite Nun, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz” (1700), designed by Joseph Caldevilla and engraved by Clemens Puche, captures these qualities. Surrounded by laurel leaves, famed Mexican poet Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz is depicted holding a pen and a book, suggesting her intellectual force and prestige as a writer.

As Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz’s portrayal demonstrates, “convents were active spaces of intellectual construction,” Safier said. “Women’s ideas were tested, challenged and created in the course of daily life.”

Similarly demonstrating women’s mobility and active intellectual curiosity, “True Portrait of the Venerable Mother Gerónima de la Asunción” by Joseph Mota (1713) captures the likeness of Gerónima de la Asunción, who is famed for her year-and-a-half long journey from Toledo to the Philippines, where she founded the nation’s first women’s convent. The emaciated Gerónima de la Asunción is accompanied by images of a whip, chains and a crown made of thorns, representing the “extreme penitential practices that were praised during this period,” Tiffany said.

Gerónima de la Asunción’s likeness inspired Tiffany when she was writing a book on the artwork of esteemed painter Diego Velázquez. With a background in European art, Tiffany continued her research at Brown as a JCB fellow between 2014 and 2015, working with experts to study nuns from the Spanish world.

Other elements of the collection provide more whimsical representations of convent culture. In an inscription in her “Oaxaca Manuscript,” María de San José apologizes for the fact that the pages are stained, as a cup of hot chocolate had been spilled onto the pages. “It’s a neat, novel window into the world of the 17th century,” Tiffany said.

With almost all displayed items coming from Brown’s resources, the exhibition has succeeded in showcasing the exceptional depth of the JCB archives, said Tara Kingsley, the JCB’s coordinator of academic programming and public outreach.

“This exhibition sheds light on aspects of the JCB’s collection that we don’t usually think of,” Tiffany said. “It’s relevant because it helps us engage with women’s history while thinking broadly about Spanish culture.”

It captures “global women’s issues in the 17th century and recognizes a lot of work that is done by women and is not … recognized as it should be,” Safier said.