The Golden Globes, affectionately known as the little (and drunker) brother to the Academy Awards, aired with much fanfare Jan. 8. Yet despite all the conversation and attention that the awards ceremony generates, the Golden Globes themselves provide relatively little insight into who will collect Oscar hardware in February. The Golden Globes occur several weeks before Oscar nominations are even announced, introducing a format that lends itself to a certain measure of awkwardness. Indeed, Aaron Taylor-Johnson, whose performance in “Nocturnal Animals” won him a Golden Globe for best supporting actor, did not even receive an Academy Award nomination. Additionally, “La La Land” and “Moonlight” both earned Golden Globes in their respective categories for best musical or comedy and best drama, though they will compete for best picture at the Academy Awards.

Such discrepancies are expected, as the separate voting bodies responsible for the Golden Globes and Oscars differ in both adjudication style and membership. Nonetheless, while the Golden Globes might not offer a precise means of predicting future Oscar winners, they, at the very least, identify and uncover the emerging narratives that will define the Academy Award season.

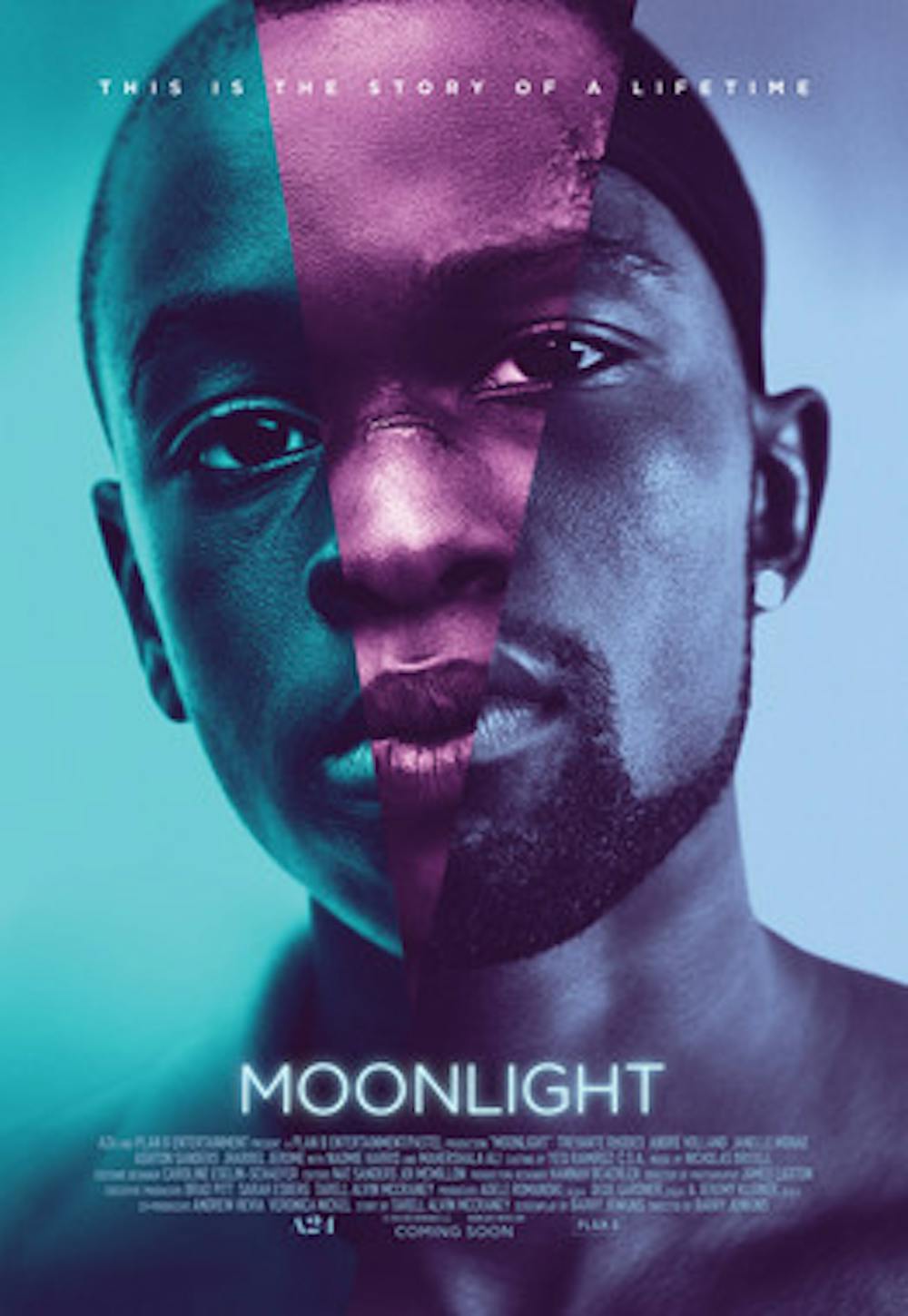

In separating “La La Land” and “Moonlight,” the Golden Globes failed to address the most contentious debate of early Oscar buzz — which frontrunner will win the best picture honor come February. Race once again dominates the awards season and is particularly central to the arguments surrounding “La La Land” and “Moonlight.” Following the #OscarsSoWhite controversy of previous years, “Moonlight,” which narrates the life of an impoverished gay black man named Chiron, comes as a tonic to the Academy’s aversion to art either celebrating black life or authored by black auteurs. It is characterized as the “serious” and “important” counter to the feel-good pastiche of antiquated Hollywood musicals in “La La Land.”

“Moonlight” suffers more from this characterization. The film falls victim to its own strengths: Critical dialogue surrounding Chiron’s experience as black, gay and male inevitably leads to bland conclusions about the movie’s “seriousness.” These conclusions allow audiences to indirectly treat the film as an opportunity to fulfill “woke-ness” quotients rather than recognize it as a legitimately beautiful art piece. “Moonlight” isn’t “important” just because of Chiron’s race and gender, but rather because of Director Barry Jenkins’ ability to communicate the suffering bound up in America’s centuries-long toxic treatment of black male sexuality. Jenkins treats Chiron not simply as a vehicle for that communication but rather as a fully-realized human being.

Discourse surrounding “La La Land” has also ventured into the cultural morass of race and gender. The film has faced criticism for Ryan Gosling’s character’s penchant for “mansplaining” jazz to co-star Emma Stone’s character. Moreover, critics argue that the film gives into cinema’s white savior narrative cliche — as Ira Madison wrote for MTV: “The wayward side effect of casting Gosling as this jazz whisperer is that ‘La La Land’ becomes a Trojan horse white-savior film … In ‘La La Land,’ the fate of a minority group depends on the efforts of a well-intentioned white man.” Criticism for “La La Land” is as unfair as that for “Moonlight”; the film is not a jazz movie, but rather uses jazz as to explore the very human flaws of its subjects. In its portrayal of two artists struggling to hone a craft, “La La Land” explores tensions between professional and romantic passions.

The undue effects of advertising space and box office success also add to the contentious nature of the Best Picture race. “La La Land” has enjoyed a stronger Oscar advertising campaign, purchasing 1,872 square inches of total advertising space compared to the paltry 266 bought by “Moonlight,” according to statistics aggregated by FiveThirtyEight. Furthermore, “La La Land” has reeled in $175 million in total box office revenues, against the $15 million brought in by “Moonlight.” These figures have only furthered the narrative of “Moonlight” as a progressive David fighting the conventionalist Goliath of “La La Land.”

Regardless of which film wins the best picture race, “Moonlight” and “La La Land” have charged the early Oscar season with competing discourses on race and gender.