University researchers developed a new ligase, an enzyme that joins together strands of DNA or RNA and has applications in biotechnology and diagnostics, as described in an Oct. 7 paper in RNA Biology.

These enzymes have many uses. Ligases play a role in the construction of DNA sequences from many smaller pieces of DNA and the identification of point mutations, said Anubhav Tripathi, professor of engineering and of molecular pharmacology, physiology and biotechnology and co-author of the study, adding that ligases can be used in sequencing and mutation detection.

Ligases can also contribute to the diagnosis of specific diseases and infections. “These techniques can be used to quickly identify, for example, viral infections such as hepatitis C,” said Lei Zhang GS, lead author of the study.

Many modern techniques used to pinpoint infections from samples and mutations in tumor tissues involve enzymes similar to ligases, said H. Benjamin Larman, assistant professor of pathology at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. “These advances rely on reagents, and in particular, enzymes that allow us to amplify or prepare libraries of molecules for analysis,” he said.

MicroRNAs — small pieces of RNA that can act as markers of diseases like cancer — can be detected through the use of enzymes like SplintR, a ligase developed by New England Biolabs and discussed in a paper published this spring, said Larry McReynolds, senior scientist in RNA biology at New England Biolabs. Like the new ligase from Brown, this enzyme can be used to detect RNA, but their methods are somewhat different. There’s overlap in the capabilities of many ligases, McReynolds said.

“This will be another arrow in the quiver that scientists can use to develop nucleic-acid based technologies,” Larman said, noting that the scientific community may find a new “killer application” for this novel tool. “Every time there’s a new way of doing things, it really opens the floodgates to discovery.”

Most ligases are used for DNA, but research in recent years has yielded a new class of ligases that operate on RNA, McReynolds said. His organization likely has the largest selection of ligases of any company, and some of the research in his lab involves finding ways to make ligases more useful, McReynolds said.

This new ligase is especially useful because of its tolerance for high temperatures. “Thermostable proteins are a niche group of proteins and are less commonly found,” Zhang said.

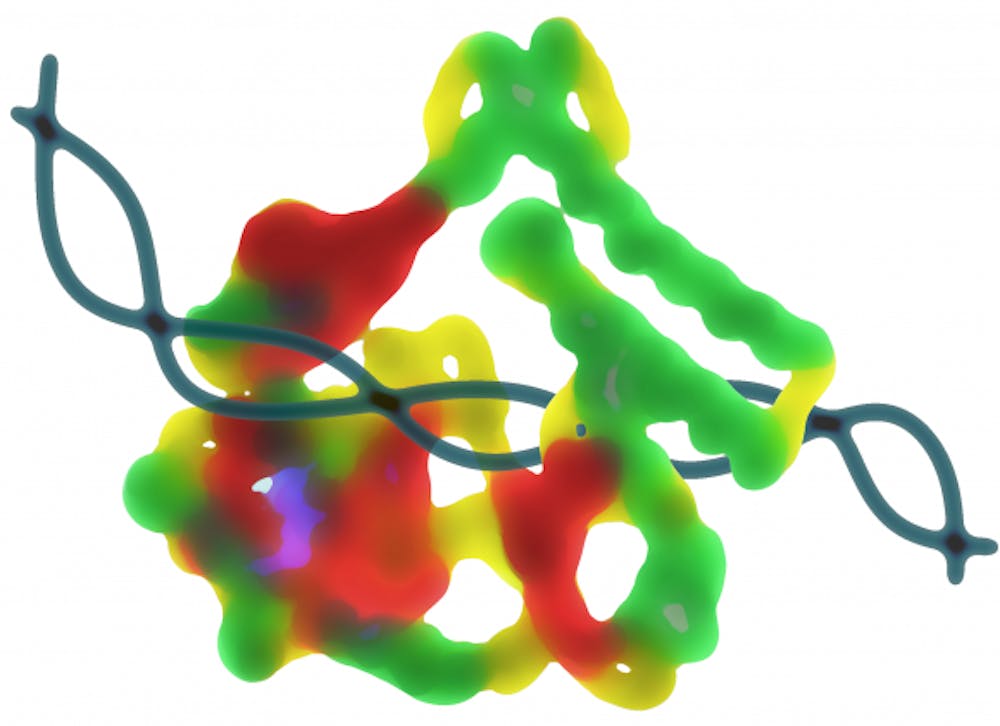

Most ligases operate at human body temperature, McReynolds said. Ligases that work at higher temperatures are desirable because RNA is “often folded up into these very complicated structures, where there’s base pairing between different parts.” When temperatures rise, the RNA will “unwind,” which makes the RNA more accessible to ligation. Because this new enzyme functions well at higher temperatures, the ligation process will hopefully be more efficient and less expensive, Tripathi said.

Additionally, the specificity of reactions can often be increased at higher temperatures. “You can sort of wash away the things that don’t bind perfectly at a higher temperature,” Larman said.