A University study published online Aug. 30 revealed a surprising discovery: a new binding formation used uniquely by two proteins during the final stages of cell division. The discovery could have implications for cancer treatment, as the proteins identified in the study play a role in cell division and therefore in the massive cell proliferation involved in cancer as well.

The discovery was that RepoMan and Ki-67 — two regulator proteins — attached to protein phosphatase 1, a multi-functioning protein involved in mitosis, in a novel pattern.

Scientists from the Research Institute for Environment, Health and Societies at Brunel University London and the Laboratory of Biosignaling and Therapeutics in Leuven, Belgium co-authored the study with University faculty members. The research relied on international collaboration among the three laboratories: The University’s lab specialized in x-ray crystallography, while the other two labs focused on cell biology, said Paola Vagnarelli, lecturer at the College of Health and Life Sciences at Brunel University London and co-author of the study.

Once the University’s lab had determined the crystal structure of the complexes, the other two labs began experimenting with manipulations inside the cells, Vagnarelli said. “They came together to make a very strong case,” she added.

The research showed how RepoMan and Ki-67 selectively interact with the gamma form of PP1, wrote Senthil Kumar, assistant professor of pharmacology, physiology and biotechnology and lead author of the study, in an email to The Herald.

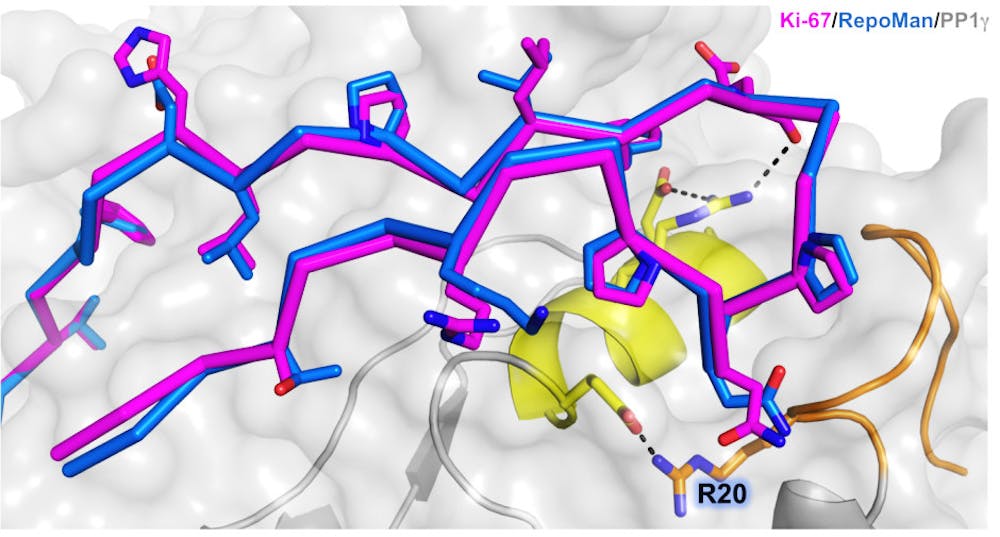

About 200 different proteins are known to regulate PP1, but the way RepoMan and Ki-67 bind is unique, Kumar wrote. “This binding with PP1 is unusual, forming a ‘hairpin’ shape at the surface of PP1 at specific locations,” he added.

The researchers named this interaction area KiR-SLiM, Page said.

Discovering this new binding mechanism involved in cell division creates potential for new cancer drugs, according to the study. This research was not intended to concentrate on cancer, but PP1 is “absolutely critical for the cell cycle, and of course cell proliferation is one of the defining hallmarks of cancer,” Page said, adding that research into the molecular structures of these complexes can be done alongside the search for cancer drug targets. The rapid cell multiplication that characterizes cancer could potentially be interrupted by drugs created based on the discovery of the new binding mechanism with PP1.

“Studies to date have really focused on kinases, which are sort of the opposite end of the chemistry equation, putting phosphate groups onto proteins,” Page said. This study investigates the proteins that separate them, and those events are necessary to stop the cell replication cycle, she added.

Most drugs act on proteins, so creating drugs requires an understanding of the atomic structures of these proteins and their interactions with other proteins, Page said. “Now we know exactly the pocket we can target that is specific just to these two proteins, so we may be able to design drugs that are specific for that target.”

But such medications may be a long way off. The concept of crafting anti-cancer drugs based on these findings is “a long-term perspective,” said Sara Cuylen, a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute of Molecular Biotechnology of the Austrian Academy of Sciences.

“RepoMan could be an essential protein (to cancer),” Cuylen said. “We first need to show whether this is important for cell division.”

Authors of the study were confident that the Ki-67 and RepoMan proteins play significant roles in targeting cancer cells. Page noted that Ki-67 has long been considered one of the “major markers for proliferating cells” and is used to track cancer advancement.

Based on evidence she collected, Vagnarelli believes RepoMan is also “very important for cancer progression.” She added that if the function of this enzyme is stopped, cells will be prevented from growing and invading.