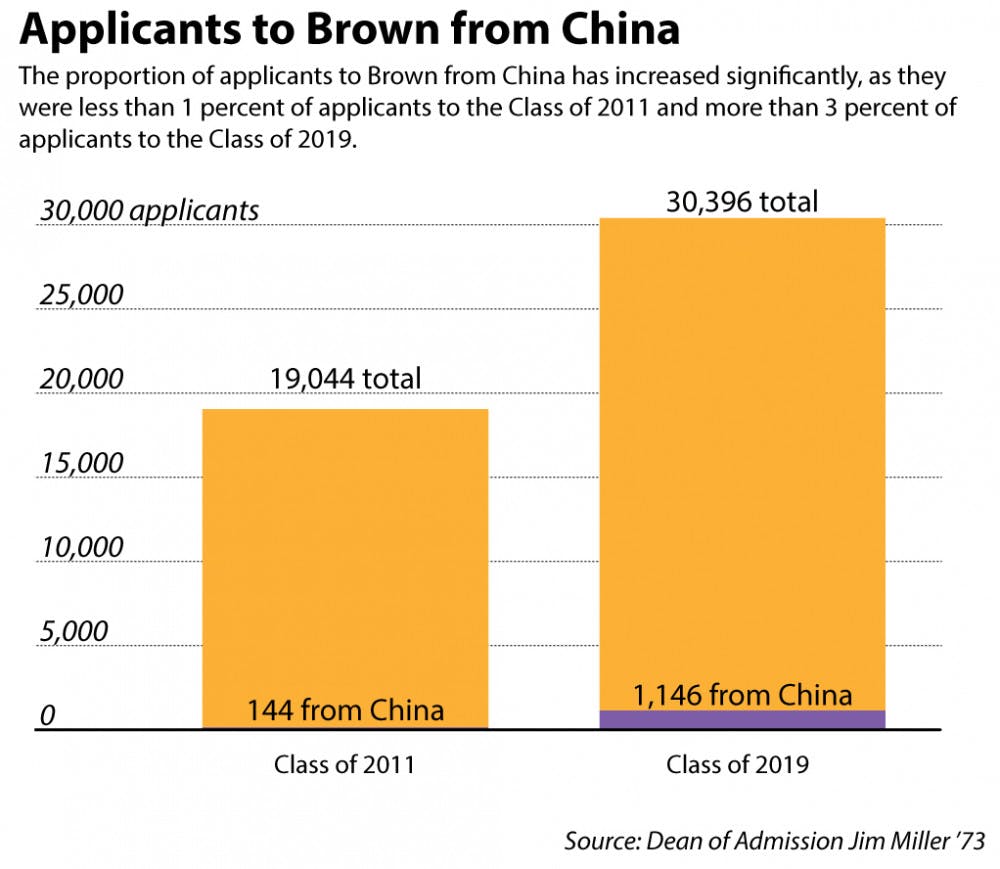

Students from China constitute the largest portion of Brown’s international undergraduate body. In 2007, 144 students from China applied to Brown, comprising less than one percent of all applicants. Last year, that number jumped to 1,146 applicants and quadrupled that percentage, wrote Jim Miller ’73, dean of admission, in an email to The Herald.

Given that China has eight to nine million high school graduates annually, “it stands to reason that it would produce the largest number of non-U.S. applicants,” Miller wrote. But many Chinese students come to Brown to escape the Chinese higher education system.

Arrya Luo ’18 said she came to the United States because she would have greater flexibility in choosing her major than in China. Students who want to attend college domestically take the Gaokao, the mandatory college entrance exam. Higher scores on the Gaokao force students to major in the sciences, Luo said. For students whose Gaokao performance is less than stellar, a science, technology, engineering and mathematics major is out of the question. “You have no choices,” she said.

Amy Xu ’19 voiced similar sentiments. “I wasn’t sure what I wanted to study while I was in high school,” she said. She knew she wouldn’t have the option to explore her interests in China.

Elaine Wen ’18 left China even earlier. Right after middle school, Wen flew to Pennsylvania to attend a private boarding school. She explained that most Chinese high schools make students choose between a science or humanities track that dictates their high school curriculum. Wen disliked how the system forced her to choose, as she was interested in both fields.

America’s education system might seem like a liberating alternative, but by applying to study abroad, Chinese students forfeit their ability to apply to national colleges. “Your high school asks you to sign a contract that says you have no regrets,” Luo said. “There’s no turning back.”

As one might expect, the application processes for Chinese and American universities differ widely. “Chinese colleges do not care about extracurriculars,” Xu said.

Only grades and the Gaokao score matter in China, Wen said.

Chinese universities also don’t require personal statements, Luo said.

Luo said she knew Brown was her top choice after attending a Brown summer program in her sophomore year.

For Xu, Brown had accepted several graduates of her high school in the past, so she knew she had an increased probability of admission. Brown also appealed to her because of its open curriculum, she said.

Wenjie Zheng ’17 said that as an international student, he lacked resources and information about many colleges. “I applied to as many schools as possible,” he said. “I let the college choose me.”

Adjusting to Brown and American culture was “surprising at first,” Zheng said. He was initially astonished by students’ awareness of sexual assault, sexuality and gender on campus. Sex is not even “talked about in China,” he said. “It’s considered embarrassing.”

Zheng also observed that time between semesters is spent differently. Chinese students focus on academics, but American students are encouraged to intern and gain work experience, he said. American students have “more exposure to real society” while they are in college, he said.

Xu said that due to the one-child policy, her parents “always protected” her and helped make decisions for her. After coming to Brown, she quickly realized that she needed to take more ownership of her choices, she said.

In spite of the relatively liberal environment of American universities, as well as Brown’s open curriculum, students voiced the pressures they feel to study in the STEM fields. “China is a developing country, … so students are encouraged to take STEM classes,” Zheng said. “Traditional parents push their kids to take STEM-field” courses because they believe they will help kids secure a job, he added.

Chinese students “rarely major in the humanities,” Wen said.

Even in high school, most students choose the science track over the humanities track, Xu said.

In general, students from China are “driven, goal-oriented (and) serious about academics,” Wen said.

“They’re very practical,” Zheng said.

Brown enrolled six students from China in 2005, compared to 29 last year, Miller wrote. While “it’s hard to predict … what will happen,” Miller wrote that “the growth in applicants and matriculants” from China will likely “continue to grow for the forseeable future.”