With Rhode Islanders heading to the polls today, the unsettled races in both parties place more importance on voters in the Ocean State than in past years.

A poll conducted by the Taubman Center for American Politics and Policy in February showed former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton topping U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders, D-VT, by nine percentage points in the Democratic race and Donald Trump leading the Republicans with an 18-point advantage over U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio, R-FL.

Sanders dominates in the cohort of voters under 45, while those above 65 favor Clinton, along with women and black voters. Among men and those above age 65, there is strong support for Trump, but 26 percent of Republican primary voters below age 45 remain undecided.

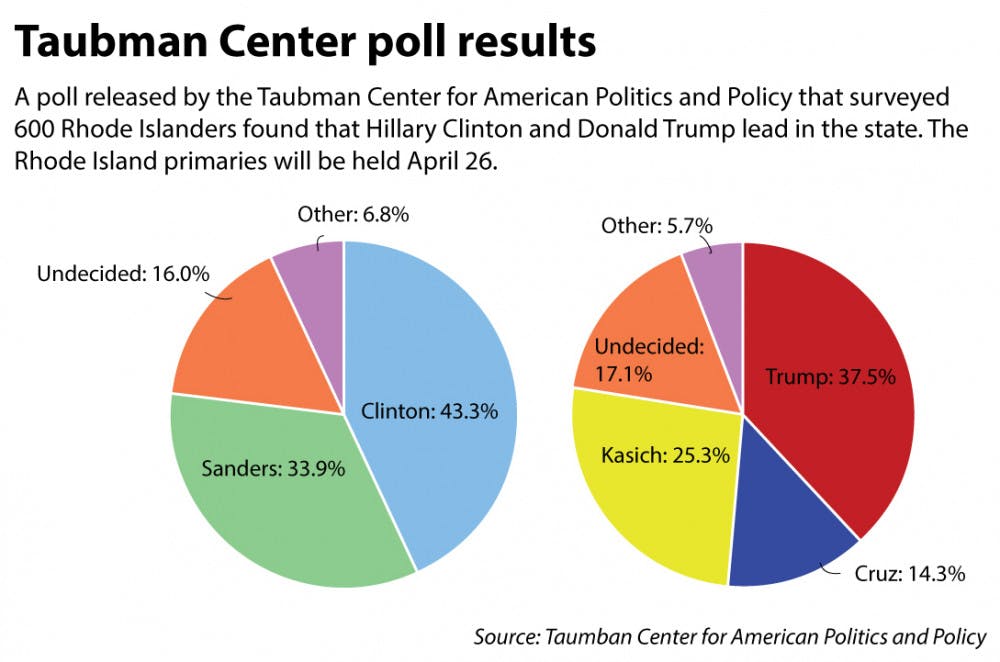

A more recent Taubman poll released Sunday showed Clinton leading Sanders by about 10 points and Trump leading Gov. John Kasich of Ohio by about 12 points.

“This is a weird election,” said Joshua Dyck, associate professor of political science and co-director of the Center for Public Opinion at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell. “Every once in a while, things happen where you get some sort of crazy outsider, and that’s exactly what we have with Donald Trump on the Republican side.”

“In some of these later races now, because they’re actually consequential, we’re seeing higher levels of turnout, and we don’t know how to predict these turnout surges,” Dyck said. “In the context of presidential primary elections, they’re unprecedented.”

Though these “turnout surges” make it difficult for pollsters to build a dependable likely voter model, polling has been generally accurate for this election so far, he said.

“This is a pretty good rule of thumb: Polls do a pretty dismal job of predicting caucuses. The record on primaries is better,” said Richard Arenberg, adjunct lecturer in international and public affairs. “There are a lot of places things could go wrong. That they don’t go wrong more often actually is a testament to why people can generally believe what they’re seeing.”

Many experts doubt the accuracy of online polls, and dropping response rates and increased cell phone use are creating problems for pollsters, as The Herald previously reported. Despite these new issues, “it’s not clear that (poll accuracy is) necessarily any worse this year than it is historically,” said Courtney Kennedy, director of survey research at Pew Research Center.

But there have been exceptions. The Michigan Democratic primary stands out as an example of poll results differing from primary results, as polls predicted an easy win for Clinton in a race Sanders won instead. “That one’s a big red flag, and I think it needs to be looked at a little more closely,” Arenberg said, adding that an underrepresentation of young voters, who more often favor Sanders, may have contributed to the inaccuracy of the polls.

Poor sampling could have been a factor, or the Michigan polls could have been a result of random error, said David Redlawsk, director of the Eagleton Center for Public Interest Polling and professor of political science at Rutgers University.

But we only hear about polling “when polls get something wrong,” Dyck said. “If that’s happening about one in 20 times, then that’s actually what we would expect through random error.”

Any single poll should not be trusted on its own, Redlawsk said, adding that a group of polls taken over similar time frames and with similar populations provides a more reliable picture.