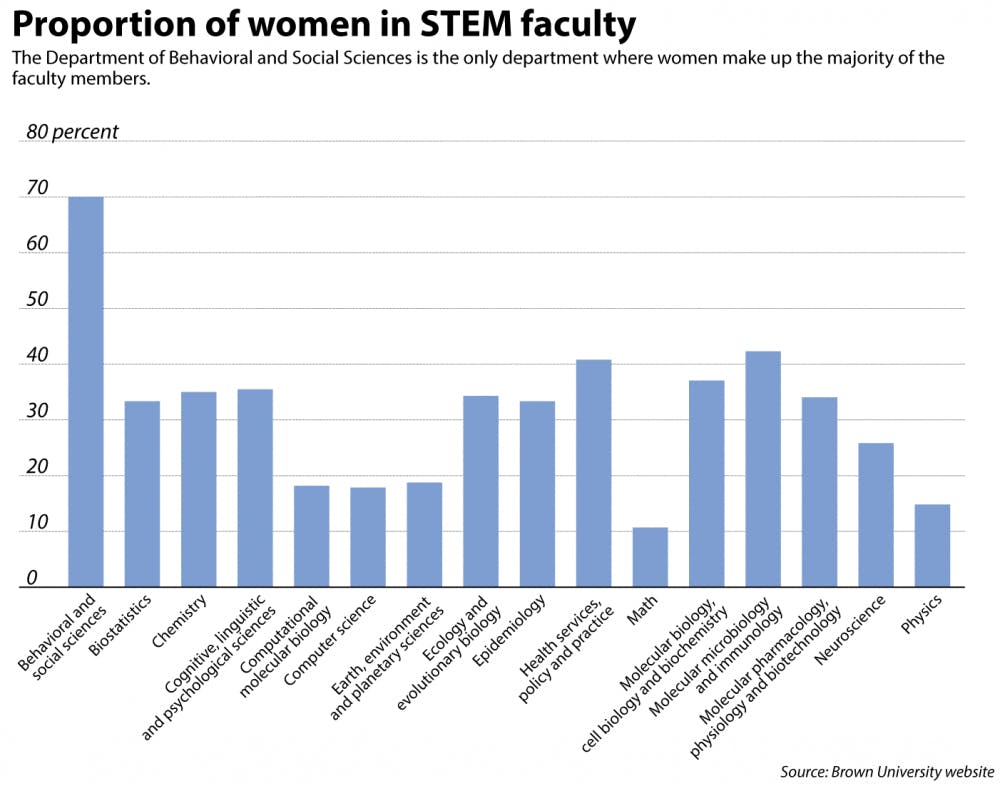

Within certain University biology departments, women make up nearly half of the faculty, and within the department of behavioral and social sciences, 70 percent of faculty members are women.

But disparities still exist within science, technology, engineering and math fields. In the applied math, mathematics and physics departments, women represent under 20 percent of faculty members, according to faculty lists on each department’s website. One department head within the STEM fields is a woman.

Nationally, the fields of engineering, computer science and physics retain the lowest percentages of women, and female representation is also low in mathematics and statistics, according to the National Science Foundation.

Debunking gender myths

In a 2005 speech, Larry Summers — then-president of Harvard — discussed the difference between men and women pursuing STEM in terms of willingness to take on “high-powered, intense work” and the greater variability of talent within the male population compared to the female population. He suggested that women’s disinterest in the greater time commitment required of STEM fields and larger numbers of extraordinarily talented men contributed more to the gender disparity in STEM fields than “different socialization and patterns of discrimination.”

Jeffrey Brock, chair of the mathematics department and professor of mathematics, disagrees with the lingering stereotype that women and men have different abilities in math. But it does come up, he said, adding that the idea is “kind of like whack-a-mole — you have to stomp it out when you see it.”

Andrei Cimpian, associate professor of psychology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, noted the misconception that women are not as capable in the sciences is not supported by his research.

Cimpian was part of a study published last year that surveyed 1,820 faculty members, post-doctoral fellows and graduate students from 30 disciplines. These subjects rated their agreement with different statements about what is required for success in their respective fields, and these numbers were used to calculate scores representing how much a field is perceived to demand inherent ability. “The fields in which this belief is most prevalent are also the fields in which there are both fewer women and also fewer African-Americans,” Cimpian said. He added that both groups are stereotyped as “less intellectually competent,” but noted that these perceptions are not drawn from reality.

“Even though people think that men and women sort themselves into fields depending on the workload required by these fields, we didn’t really find any evidence of that,” Cimpian said.

He also noted that his research found no support for the greater variability hypothesis referenced by Summers, which would suggest there are more male geniuses than female ones.

Differences between genders?

Some sources pointed to differences between the genders to account for the disparity between various STEM fields.

“Many women are simply raised to believe that they’re supposed to be caretakers, supposed to prefer biology to, say, chemistry or physics,” wrote Eileen Pollack, author of “The Only Woman in the Room: Why Science Is Still a Boys’ Club,” in an email to The Herald. “I remember being told — repeatedly — that I shouldn’t want to major in physics because studying people and living creatures would make me happier. But I didn’t feel that way on my own.”

“Women have a real tendency to be drawn towards career paths where they can see that they are making a positive impact in other individuals’ lives or in society at large,” said Katherine Smith, associate dean of biology undergraduate education and assistant research professor of ecology and evolutionary biology. “Perhaps the biological sciences offer women the opportunity to do that in a more clear way than some of our physical science analogues do.”

Amara Berry ’17 said she was discouraged from an initial interest in physics throughout high school and pushed to study a subject in the humanities. Now, her interests have shifted, and she decided to concentrate in Gender and Sexuality Studies.

“Any kind of penchant towards caretaking is socially constructed — not natural,” Berry said.

“I always have thought that biology and (cognitive science) are very relevant to the life someone lives,” said Adrianna Wenz ’18, who switched her concentration from English to neuroscience. “That’s very relevant to when you see someone dying. You can help them in real time.”

“In biomedical engineering, you’re creating something that no one has created before, and you actually have the power to directly transform a life,” said Tanaya Puranik ’19.

Bethany Dubois ’18 said she felt unaware of the gender disparity in math and science until she arrived at Brown. Now a physics concentrator and pre-medical student, Dubois noted that the same skills she liked using in physics, like problem solving and applying knowledge, also drew her toward medicine.

Dorit Rein ’18, a computer science concentrator, said that women may need social interaction to be successful, more so than men. Because social interaction is integrated more heavily into certain fields like medicine and psychology and is emphasized less in fields like computer science, women may be deterred from entering those fields.

Devanshi Nishar ’18, a computer science concentrator, pointed out the increased severity of collaboration rules for computer science introductory courses this year as a drawback for women in the department.

“I made such great friendships in (my introductory courses), and that was partially because we could talk about things,” Nishar said. “How can you build up a support network for yourself if you can’t talk about the things you’re working on?”

“At Brown, specifically with computer science, the first two years are so difficult, and it really pushes away a lot of people from continuing to concentrate,” Rein said. “The people that hurts the most are women, people of color and underrepresented minorities in general.”

Björn Sandstede, chair of the applied mathematics department, noted his department has begun replacing some recitations with problem-solving sessions. Students “can form teams in a way that helps them form a community,” which has seemed to help female students so far, he added.

A 2011 study by Sadan Kulturel-Konak at Pennsylvania State University, Berks, indicated that women and men benefit from different teaching styles. Her study showed that men appreciate a more analytical approach — the style in which many STEM classes are taught — while women prefer a more hands-on technique. Kulturel-Konak’s research concluded that because more STEM classes are taught in an analytical style, women have begun to lose interest in STEM courses.

But studies about learning differences amongst the sexes have varied greatly since the topic began to gather interest in the 1980s. In Diane Halpern’s 2012 book, “Sex Differences in Cognitive Abilities,” she explained that differences in learning are generally unsupported by research.

Instead of considering societal and historical forces, individuals tend to assume the inherent abilities of men and women influence their success, Cimpian said.

Push factors

While some factors might pull women toward fields like psychology and biology, other factors push women out of fields like applied math and physics, sources said.

Pollack earned a degree in physics from Yale, but she ultimately abandoned the field to pursue writing. Her book investigates the confluence of factors that keep women out of STEM fields like physics.

“Most people tend to think that only a genius can succeed in a field such as physics or math, especially the more abstract, theoretical branches of those fields,” Pollack wrote.

Expectations of brilliance likely affect mathematics specifically, said Jill Pipher, director of the Institute for Computational and Experimental Research in Mathematics. She added that people may assume some fields are more accessible than others based on how difficult to learn or innate the required skills are.

“It’s true that there’s a little bit of a mystique associated (with) doing math,” said Melody Chan, assistant professor of mathematics. She added that there is a “premium placed on this mysterious quality of genius.”

“Physics definitely has this association where people tend to think you’re just good at it, or you’re not,” said Källan Berglund ’16, a physics concentrator.

Berglund added that she feels sad to hear people say they are bad at math. “They say it like it’s part of their identity,” she added. “A lot of them say it proudly.”

Echoing this sentiment, Shipra Vaishnava, assistant professor of molecular microbiology and immunology, noted that society condones a lack of math skills in girls. “It should not be okay. You should always be trying to get better at math if you’re not.”

Across disciplines, there are many factors that influence success, ranging from hard work to fearlessness in the face of inhospitable environments. “Geniuses come in all races and genders,” Pollack wrote. “No one is even sure what makes a genius a genius. Intuition and confidence might be as important as raw IQ.”

A lack of representation may also cause a vicious cycle in certain STEM departments, as students who see other women at work within their fields may feel more at ease within those spaces.

Raphae Posner ’18, a student in the Program in Liberal Medical Education, said that she has valued working in a lab of mostly women. “I have had really great role models who appreciate the importance of young women in science,” she said.

Departments with lower proportions of female faculty members have expanded their efforts to retain female students. The lack of representation can discourage women from considering those fields, Berry said.

“Physics can have a much colder environment,” Dubois said, citing the lack of visibility of underrepresented minorities in teaching assistants. “Nearly everyone that I’ve interacted with has been male or a well-represented minority.”

Brock said that within the math department “there’s a high point of attrition around sophomore-level courses — this is where you’re first exposed to abstract mathematics and proofs.” The department is working with a group of undergraduates to redesign the curriculum in an effort to increase retention.

People often turn to the few women in the department with their questions. “I feel like this is taking an immense amount of time and energy from my studies,” Berglund said.

Chan recently started a mentorship program to connect undergraduate women with female graduate students in the math department, describing it as “a low-key way to build community.”

Though the math department currently has two tenure-track female faculty members, Brock said, female representation in the department is greater than that found in many math departments at other universities.

“I do feel really positive about what I’ve seen from the department,” Chan said.

Intersectionalities of race and gender

“Most of us picture geniuses as looking like Albert Einstein — that is, as white men with crazy hair,” Pollack wrote.

“Implicit biases make us think that people of color aren’t as competent in the sciences,” Berry said. “You’ve got this system that produces the same kind of thinkers over and over again.”

As a black woman in engineering, Yasmine Hassan ’17 feels that different expectations are placed on her. Others have “mansplained” concepts to her, taken tools out of her hands and doubted her answers. “I can’t extract specifically my gender or race.”

Professors, more than other students, have made Hassan feel as though she doesn’t belong.

Hassan is a member of the National Society of Black Engineers, but she is not involved in the Society for Women Engineers or the group Women in Science and Engineering.

“I don’t know how comfortable I feel in those spaces,” she said, adding she sometimes feels that “the STEM feminist agenda is very much colorblind.”

Nishar pointed out that tech companies are quick to highlight their diversity initiatives, but focus more on gender balance in the workplace, rather than diversity of race or sexuality. “If they can just hone in on this one aspect — being a woman — then do they really care about diversity in the first place?” she asked.

Correction: The previous version of a graphic accompanying this article mislabeled the proportion of women in the math, molecular biology, cell biology and biochemistry, molecular microbiology and immunology, molecular pharmacology, physiology and biotechnology, cognitive, linguistic and psychological sciences and computational molecular biology departments. The Herald regrets the error.