The Providence City Council voted unanimously March 3 to support efforts to memorialize victims of the transatlantic slave trade and their descendants. The resolution formalizes the council’s support of the work being done by the Rhode Island branch of the Middle Passage Ceremonies and Port Markers Project to erect a marker in the city in an effort to acknowledge the state’s historical association with the slave trade.

“In voicing their support, they help create awareness of the project on a broader level,” said Michaela Antunes, press secretary for the Providence City Council. The resolution also indicates the city’s willingness to cooperate with the project and “facilitate anything that needs to be done on the city’s end,” she said.

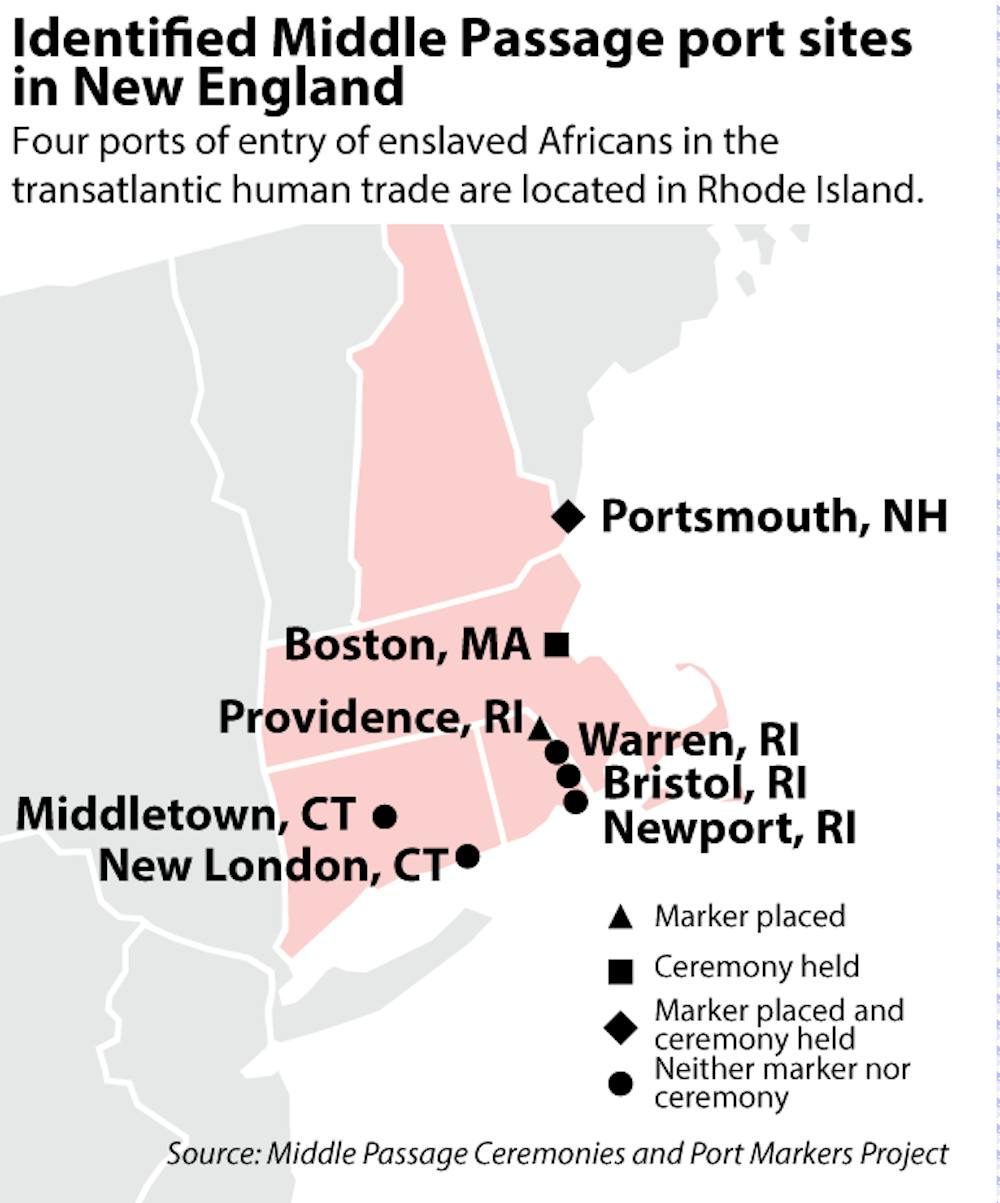

The Rhode Island Middle Passage Project is part of a larger national organization that seeks to erect memorials and hold ceremonies honoring the plight of enslaved Africans as well as the role they played in building communities across America. To that end, the project has erected memorials and held ceremonies from Texas to Maine, a fact that is indicative of the far-reaching nature of the American slave trade.

“It was a phenomenon that involved the entire United States,” said Anthony Bogues, professor of Africana studies and director of the Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice. A common misconception is that slavery was a phenomenon solely limited to the South, and while the majority of slave-holding plantations were located in Southern states, the actual financing of the trade was centered in the North, Bogues said.

During the height of the transatlantic slave trade, Providence was one of the most active ports responsible for the transfer of slaves between the African continent and other American cities, Bogues said. Providence had extensive shipbuilding and rum distilling industries as well, implicating many of the city’s residents in the slave trade, he added.

“Because Rhode Island was so involved in these other industries, small towns like Bristol were towns in which everybody was involved,” Bogues said. “You weren’t a slaver, but you worked in one of those industries, so it impinged upon a vast majority of people’s lives,” he added.

The University has also been implicated in the slave trade, as its eponymous Brown family was widely known to have participated in the slave industry. The University has taken steps in recent years to address its past, including the formation of the University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice in 2003. The committee offered a number of solutions to grapple with the University’s tainted past, but most importantly, offered a forthright acknowledgment of the University’s entanglement with slavery.

“The way the University confronted (its) past is the way the United States should,” Bogues said, adding that “not many institutions or countries have done that.”

“Brown brought it to the forefront,” Antunes said, adding that the University’s acknowledgment of its past may have influenced City Council members who thought that Providence’s role in the slave trade “deserved to be elevated to the forefront of conversation on the city level.”

That conversation now includes the potential for a new marker in the city. The design of the Providence marker will be coordinated with other projects in Rhode Island to be located in Bristol, Newport and Warren, said Emily Kugler, a member of the national advisory board for Middle Passage Ceremonies and Port Markers.

“These markers are an important way to acknowledge the people who survived the Middle Passage and their descendants,” Kugler said, adding that “when it’s well placed, someone who may not be looking for that history can learn about it.”

Funds for the project will be raised by local organizations, Kugler said, though in the past, cooperation with larger entities like the National Park Service has allowed for a reduction in the cost of projects. She added that it will likely take 12 to 18 months of planning before a ceremony is held and a marker is placed.

It is also important to note that memorials like these not only record the sins of the past but also acknowledge the legacies they have left on our modern society, Bogues said. The ball and chain memorial designed by National Medal of Arts recipient Martin Puryear located on the Quiet Green is a perfect representation of this truth, he added.

“If you look at the memorial we have on campus, the chain is broken, but it is incomplete,” Bogues said, adding that “slavery is finished, but the legacies of structural racism continue to this day.” Confronting a problematic history in this context is the first step in a long process that does not have a predetermined path, Bogues said.

“We have a lot of work to do because the legacies are still present,” Bogues said, adding that additional efforts like extended education of the Providence community are warranted given both the city’s deep-rooted history with the slave trade and the legacies that persist as a result of it.

“This memorial should not be seen as a close of a chapter,” Bogues said. “It is rather a call to further action.”