Updated Sept. 30, 2015 at 5:10 p.m.

When Christoph Lindner, professor of media and culture at the University of Amsterdam, first encountered the High Line park in New York City, he was “seduced by the whole project.”

“Then that relationship began to sour,” he said.

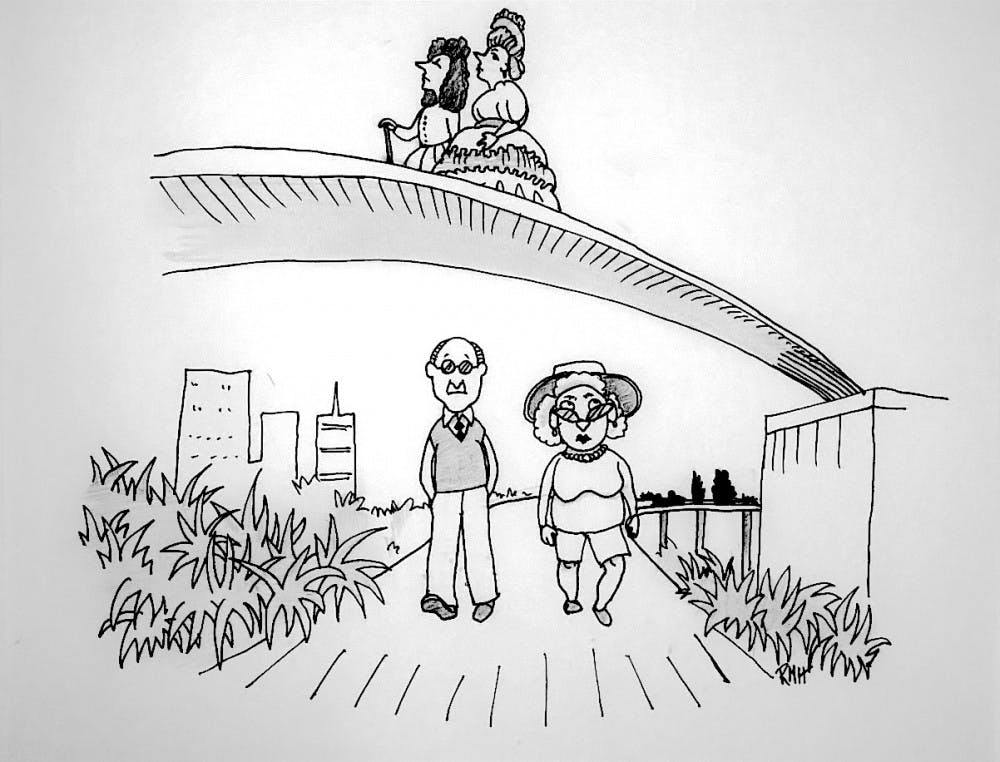

Lindner discussed the High Line — a park created on a crumbling, weed-covered elevated railway — and its negative repercussions in a talk entitled “The High Line, Supergentrification and the Street,” which was presented by the Department of Urban Studies. The department invited Lindner because of a growing interest in fostering international connections with other academic institutions, said Samuel Zipp, professor of American studies and urban studies.

Though Lindner said he has enjoyed spending time at the High Line, “the time is now right to begin also trying to critique and analyze the project.”

The High Line project was designed to revive the “so-called dead space,” Lindner said, adding that the park is a place “where people go to be slow and, increasingly, have to be slow.”

He is referring to an “ironic, unintended form of slowness”: pedestrian traffic jams caused by the park’s 5 million annual visitors. People want to visit the High Line, but it is not much of a sprawling and spacious park — tourists might instead recall the bustling airport security lines they just left.

The first problem Lindner pointed to is the design. According to the High Line website, “the movement to save the High Line was catalyzed by iconic photographs taken by Joel Sternfeld in 2000,” showing “the wild beauty of the self-seeded landscape.”

But the result is far from “wild,” Lindner said. The park is carefully planned and built to last as long as possible, according to the High Line website.

It also siphons visitors in a straight line from entrance to exit, said Deitrich Neumann, professor of history of art and architecture and director of the urban studies department. Overall, it presents a fairly stifling, uncreative experience, he added.

But the more popular the High Line becomes, the more desirable the surrounding property becomes, Lindner said. “The skyline itself is being transformed by the popularity of the park.”

The result is supergentrification: a phenomenon in which the superrich push out the rich, often very quickly, Lindner said.

The superrich are “parking their cash” in property, leaving mansions that are often “uninhabitable and uninhabited” at a time when the need for affordable housing is increasingly dire, he said.

Lindner also dove into the bizarre world of architectural renderings — mostly computer-generated images — aimed at selling developments to the superrich. One planned building near the High Line was depicted with a moat and old-style blimps floating in the background. People that seemed to be taken from a French palace were scattered throughout, some playing croquet. Lindner said he likes to call this the “Steampunk-Quatorze” style, pointing out how out of place it is among the existing buildings. It seems “generic,” the result of globalized markets ignoring the local culture, he said.

The central criticism Lindner offers is that all of these developments are essentially projects for people to make and save money. Referring to a picture of the plan to turn the iconic Battersea Power Station in London into luxury apartments, he said the image screams: “We are going to try to make as much money as we possibly can.” If these projects do not end up helping the existing community, it is because they were not really meant to help, he said.

Members of Lindner’s audience were intrigued by his critical view of the High Line. “I really thought he gave us the framework to think about other problems,” said Robert Lee ’17. “It’s going to be useful in the future.”

“We are a part of the class that is the beneficiary of this … even if we’re thinking critically about it,” Zipp said.

Amanda Boston GS said she “appreciated his discussion of the ways that gentrification has really just escalated” but is curious to know more about the repercussions for low-income people.

Lindner said he expects that if people “unpack what’s happening in the High Line, and then look in our own communities, we’ll see other versions of the same thing happening.”

But other growing housing projects keep the well-being of their residents in mind, Lindner said, citing the more positive impact of housing projects in the Netherlands that have “a commitment … to develop spaces that are not driven or beholden to the need for profit.”

ADVERTISEMENT