A March 2-3 Herald poll revealed that students who identify as LGBTQ experience greater feelings of inadequacy than their counterparts in a variety of categories. Respondents answered the question “Do you feel inadequate relative to other Brown students?”

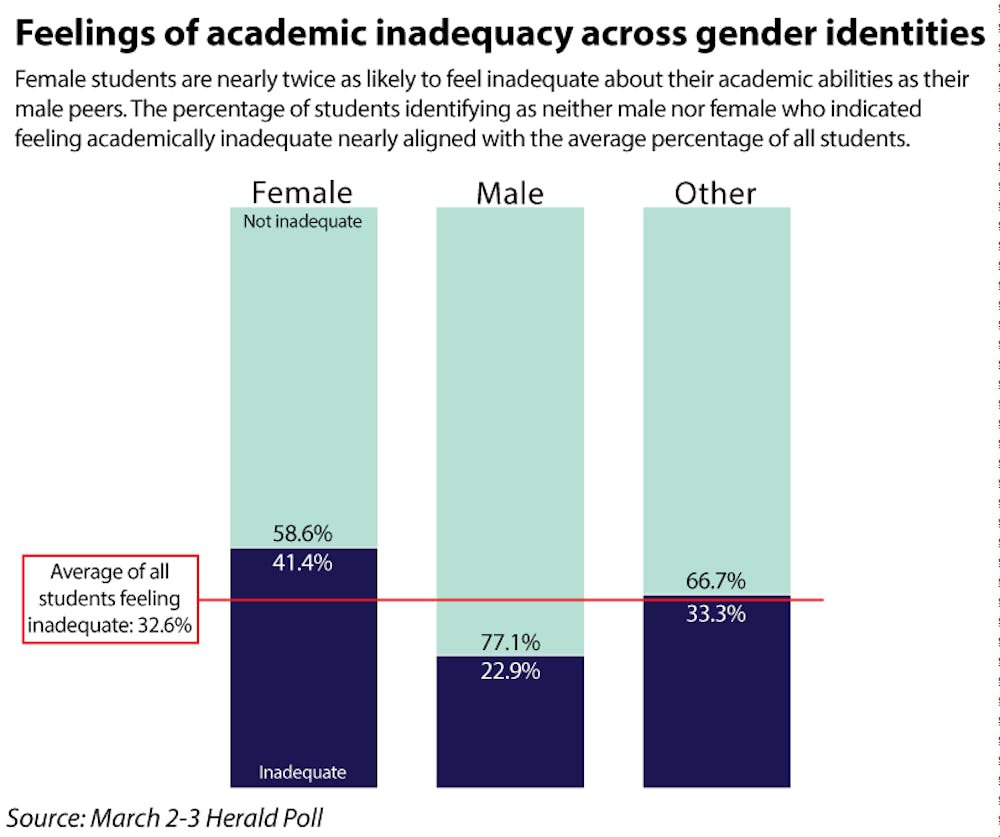

Among the undergraduates surveyed, 32.6 percent responded that they felt inadequate with regards to their academic abilities, 19.3 percent with regards to their social lives, 20.1 percent with regards to their sex/love lives, 14 percent with regards to their appearances, 16.6 percent with regards to their socioeconomic status and 9.3 percent about a factor not listed in the question.

About 43 percent of students responded that they do not feel inadequate compared to other Brown students.

Across all factors of inadequacy that the poll addressed, non-heterosexual students indicated feeling more inadequate.

“A lot of queer students here intersect with other identities,” causing pressures from each to compound upon one another, said Justice Gaines ’16.

“Brown oftentimes acts like these problems are inevitable, but they’re not,” Gaines said. The University can minimize these issues of inadequacy “not only by changing conversation but by making sure that policy is reflecting what students need,” Gaines added.

Though Adrian Lev Guerra’s ’16 personal experience as a queer student at Brown has been “really magical” on all fronts, he acknowledged that the LGBTQ identity can exacerbate pressures from other spheres of life.

While Lev Guerra said he has not felt inadequate at Brown, he has felt that way in his home nation of Costa Rica, “because the social expectations were different.”

Overall, the largest demographic gap within the results was between women and men regarding their academic self-confidence. About 41 percent of women, compared to about 23 percent of men, indicated they felt inadequate about their academic abilities.

Aly Todich’ii’ni Lawson ’18 said this discrepancy is partially rooted in the makeup of Brown faculty. “The people that you’re learning from … are usually white males. The texts that you’re reading from are usually written from a male’s perspective,” she said, adding that it is more difficult for women to “hold themselves (in) as high” esteem because of these biases in the classroom.

Disparities in perceptions of inadequacy also correlated with ethnicity. About 48 percent of Hispanic students indicated they feel insufficient with regards to their academic ability, while about 31 percent of non-Hispanic students indicated such feelings.

Andrea Cordova ’17, who identifies as Latina, noted the lack of Hispanic faculty as central to this statistical gap. “It might not make (Hispanic) students feel as comfortable as other students who are represented in the faculty,” she said.

Nicolas Montano ’17, who identifies as Latino, said while he acknowledges his socioeconomic privilege, he is conscious that some Hispanic students from working class families have a set of financial stressors that wealthier students are completely ignorant of. Consequently, these more privileged students “have a lack of context” when they interact with students from working class and low-income backgrounds, he said.

Cordova said she does not think of her financial stressors “as linked to her Hispanic identity,” but she noted that this may not be true for all Hispanic students on campus.

Similarly, black students reported higher instances of inadequacy based on socioeconomic class. For Maya Finoh ’17, this is directly related to larger patterns of discrimination in American history, such as the slave trade and Jim Crow laws, she said. “I’m not surprised by the statistics regarding socioeconomic status,” she said. “Historically, black people in this country have suffered from generational poverty because we have been constantly discriminated against.”

In contrast, athletes expressed lower levels of inadequacy with regards to their social lives, appearances and socioeconomic statuses, while international students expressed lower levels of inadequacy with regards to their academics, social lives, sex/love lives, appearance and socioeconomic status.

Augusto Ballón ’18, who is from Peru, said that in his experience international students, especially those who have previously lived away from home, find it easier to be truly independent when they arrive at college.

Jessica Kenny ’17, who is from Brazil, said her identity as an international student has given her the ability to “know how to live among differences.”

For Rob Hughes ’17, a member of the football team, confidence among athletes is linked to the inherent support provided by one’s team. Upon arriving at college, athletes find that their team members “love and respect you no matter what your class status or anything like that is. You feel like you have a big network, regardless of where you are,” he said.

“In many cases, athletes are forced in their specific sport to gain … confidence,” said Lawrence Kemp ’17, a member of the men’s lacrosse team. “That can leak into other parts of life so that can be why you see those trends.”