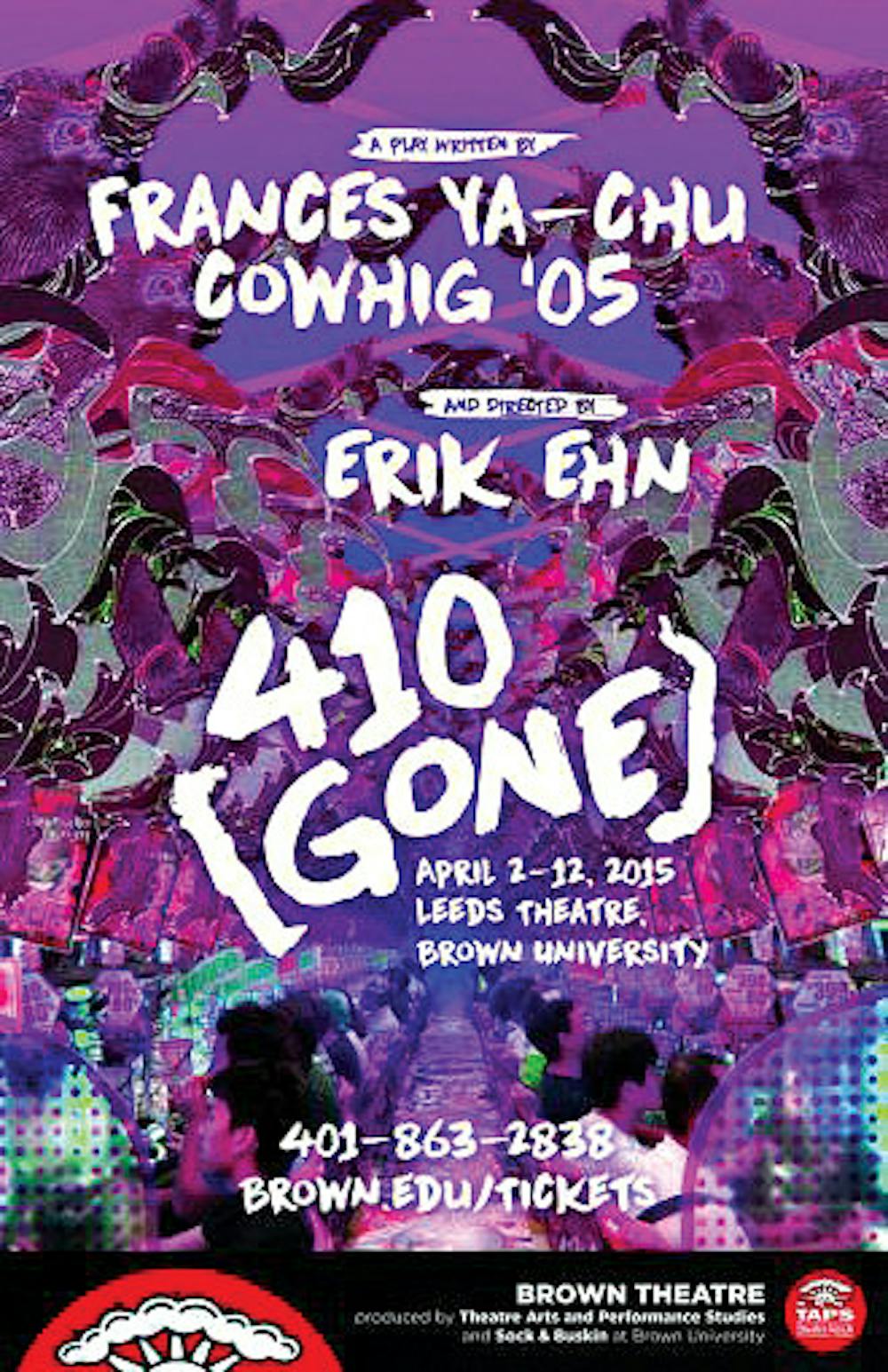

What do Dance Dance Revolution, a jar of pickles and the Chinese land of the dead have in common? The answer is absolutely nothing, unless you are familiar with the story of “410[GONE],” the latest production staged by Sock and Buskin, which opened Thursday at the Leeds Theater.

The semi-autobiographical play was written by Frances Ya-Chu Cowhig ’05, who first conceived of the piece while a student at Brown, said Paul Margrave, publicity and box office coordinator for the Department of Theatre Arts and Performance Studies. The story centers around Seventeen, a Chinese-American boy played by Bee Vang ’15.5 who has killed himself and is now passing through the land of the dead. There, he meets an assortment of strange characters: Ox-Head, played by Lizzy Callas ’15, the Goddess of Mercy, played by Ziyi Yang ’16, and the Monkey King, portrayed by Pei Ling Chia ’15 — all characters from traditional Chinese legend. While Seventeen grapples with this strange new world into which he has been thrust, the audience also meets his sister, Twenty-one — played by Kathy Ng ’17 — who is struggling with the loss of her baby brother.

The details of the show are complex and often culturally specific. There are several obscure references to Chinese beliefs and folklore, which are bizarrely juxtaposed with American pop culture references. The popular arcade dance game, Dance Dance Revolution, is the mechanism by which souls transmigrate into the afterlife. The Goddess of Mercy, instead of an omniscient spiritual being of peace, is a sardonic, jaded slacker wearing black jeans and biker boots under her goddess costume and purple wig.

The production brims with culture clash, a phenomenon reflected by the often jarring electronic dance music that alternates with soft, melodic instrumental tunes. At times, it is almost too much to take in — the context of Chinese legend is difficult to comprehend for those who are not familiar with it, and the characters sporadically slip into exaggerated Chinese accents, pronouncing their l’s like r’s as if imitating offensive racial caricatures.

“Stylistically, (the production) takes up certain challenges,” said Erik Ehn, the play’s director and chair of the TAPS department. But “the story is not so far out — there are plot points to follow all the way through, and I wanted to make sure we told a simple story simply, even while we were involved with gods and ghosts,” he added.

In theater, “there are a lot of challenges and a lot of decisions to make, but that’s what you’re in it for, the fracture and fall of it,” Ehn said. “You want a chaos to stumble forward through.”

Though “410[GONE]” may have its confusing moments for those uninitiated to Chinese culture, the story is ultimately carried by universal emotion that shines through the cultural elements, supported by the explosive performances of its talented cast. Yang and Chia have insuppressibly energetic and hilarious on-stage chemistry, providing the audience with witty one-liners, shouting arguments and even a full-out physical altercation. Vang and Ng, on the other hand, balance the hysteria with nuanced and heartfelt expressions of sadness, confusion, inner turmoil and ultimately love.

“It’s a very direct but sophisticated and unusual love story,” Ehn said, adding that “401[GONE]” discusses “love not in the romantic sense, but the absolute sense.”

Themes of love, religion and attachment run throughout the script, Ehn said. In addition, “there are particular issues related to suicide, and we want to face those squarely, along with Asian-American issues of identity and acculturation.”

Sock and Buskin hopes to inspire conversation about Asian-American cultures and how they deal with mental illness, suicide and death, Margrave said. “410[GONE]” “looks at suicide and mental health in the Asian-American community — that can be a really difficult subject to talk about,” he added. “The play is trying to find ways into that conversation — and I think (it’s) going to do that incredibly well.”

Sock and Buskin will co-host a series of dinners and talks on this topic with Counseling and Psychological Services and the Brown Center for Students of Color, Margrave said. The last dinner conversation, scheduled for the evening of April 14, aims to give audience members a chance to reflect on their experiences, he added.

“I couldn’t be happier with the conversation that’s (already) been going on onstage and backstage,” Ehn said. “A play is not just a show that we put on, it’s not just what happens when the lights go down — it’s when the light in your head turns on.”

“I’m from Hong Kong ... but I went to an American international school back home,” Ng said. “So I feel like I don’t have direct experience with what (my) character has gone through, growing up in an isolated place where Asians aren’t commonly found.” She added that she found her character often demanding and selfish, something difficult to relate to herself.

Ng said many of her Asian-American friends are very excited about the show and its subject matter.

“I’m not the loudest activist, but I’m glad that I get to be a part of something that promotes conversation,” she added.

“It’s a very personal story and one that’s very specific to Asian-American identity. ... I hope people who come to see it will be exposed to a sincere story that’s from a part of America that’s not always talked about,” Ng said.

But when watching the play, even a person who cannot relate to Asian-American culture at all would be able to appreciate the universal themes of love, loss and longing that are expressed throughout. Underneath all the references, “410[GONE]” is ultimately a twist on the story of Orpheus and Eurydice — and like Orpheus, Twenty-one learns that “the best thing you can do sometimes for someone that you love is to let them be on their way,” Ng said.

“The perfection in love is so vast that we can’t hold it,” Ehn said. “To live life fully, you have to learn from love the art of letting go.”