The State of the Union always seems to be a time for hyperbole, excitement and drama. Whether it’s Ronald Reagan returning to public life after an assassination attempt or Richard Nixon proclaiming in 1974 that “one year of Watergate is enough,” the annual State of the Union never fails to entertain. In his column “Does the State of the Union really matter?” last week, Ian Kenyon GS writes, “I feel no different than I did prior to hearing the address.” Yet though the State of the Union may no longer be as instructive as it once was, I’d suggest that Kenyon listen closer.

President Obama’s State of the Unions have been filled with fanfare. Congressman Joe Wilson heckled the president in 2009, yelling “you lie” in response to Obama’s comments about healthcare for undocumented immigrants. In the most recent State of the Union, Republicans applauded Obama when he said, in jest, that he had “no more campaigns to run.” Obama’s response has become an Internet phenomenon, appearing in numerous Vines and YouTube videos.

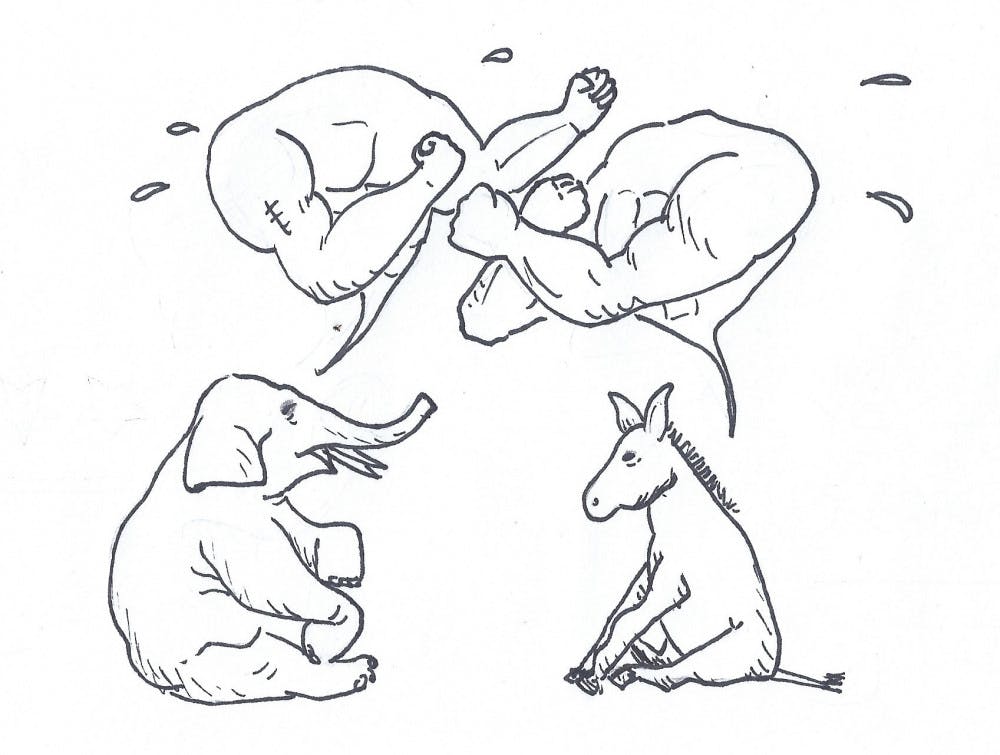

Though they are entertaining, these types of catty, political exchanges are detrimental to governance and are indicative of greater problems within the social climate of Washington: specifically, a lack of respect. But who is to blame? And here is why the State of the Union matters: The president’s language provides a lens through which to gauge the magnitude of polarization in the capital.

Obama’s rhetorical brilliance is easy to marvel at, but the message he delivered reflects a divisive D.C. climate. This is not unique to the president, and it is definitely present on both sides of the aisle. But it is clear that the his rhetoric in the State of the Union embodied the folly of modern-day Washington to its fullest extent.

There are a couple of notable examples of the president’s language and its consequences. Obama’s word choice in relation to raising the minimum wage has been simplistic. For instance, Obama said, “If you truly believe you could work full-time and support a family on less than $15,000 a year, go try it. If not, vote to give millions of the hardest-working people in America a raise.” Though living on $15,000 a year would be impossible for most, to equate raising the minimum wage with “giving America a raise” oversimplifies a complex discussion about wages in the United States.

Even a student in an introductory economics class learns that there is trade-off between greater employment and price ceilings that limit the number of people who actually attain employment. If fewer people are employed, does it really matter that some got raises? And is the overall wealth of the United States going to rise through an increase in the minimum wage?

Obama has made Republicans seem heartless and uncaring for opposing a minimum wage hike. But what Republican representative would not want his constituents to earn more? This type of rhetoric forces the opposition into a difficult political situation. Notwithstanding this strategy’s ingenious conception, it is the type of political discourse that creates needless rifts and cools personal relations.

Another example of this type of language politics, one that Washington Post columnist Robert Samuelson describes as “bumper sticker politics,” was when Obama claimed we needed an “economy that works for everyone.” Yet there is no barometer to determine whether or not an economy works for everyone. Making the economic pie larger may be better for everyone than a more equitable distribution of the current pie, which the president would define as “working for everyone.” Or, does the president imply that an economy can only be considered successful if wealth is distributed more equally? I am left unconvinced either way. This zero-sum view of capitalism promoted by the president oversimplifies and glorifies the past.

Democracy is a social sport. It requires not only competition but also mutual respect. While telling the president that he is a liar may feel good, it is harmful to the main purpose of a legislative body: to legislate. In order to have a functional governing body, it is necessary for politicians to increase civility and build personal relationships. Obama has never called Sen. John Cornyn, R-T.X., the number two Republican in Congress. Former House Speakers Newt Gingrich and Richard Gephardt had a notably frosty relationship, according to several media reports, and allegedly spoke only a handful of times.

I hope that the American people demand better from their politicians and that the Democratic president and Republican congress can transcend the barriers of language politics.

ADVERTISEMENT