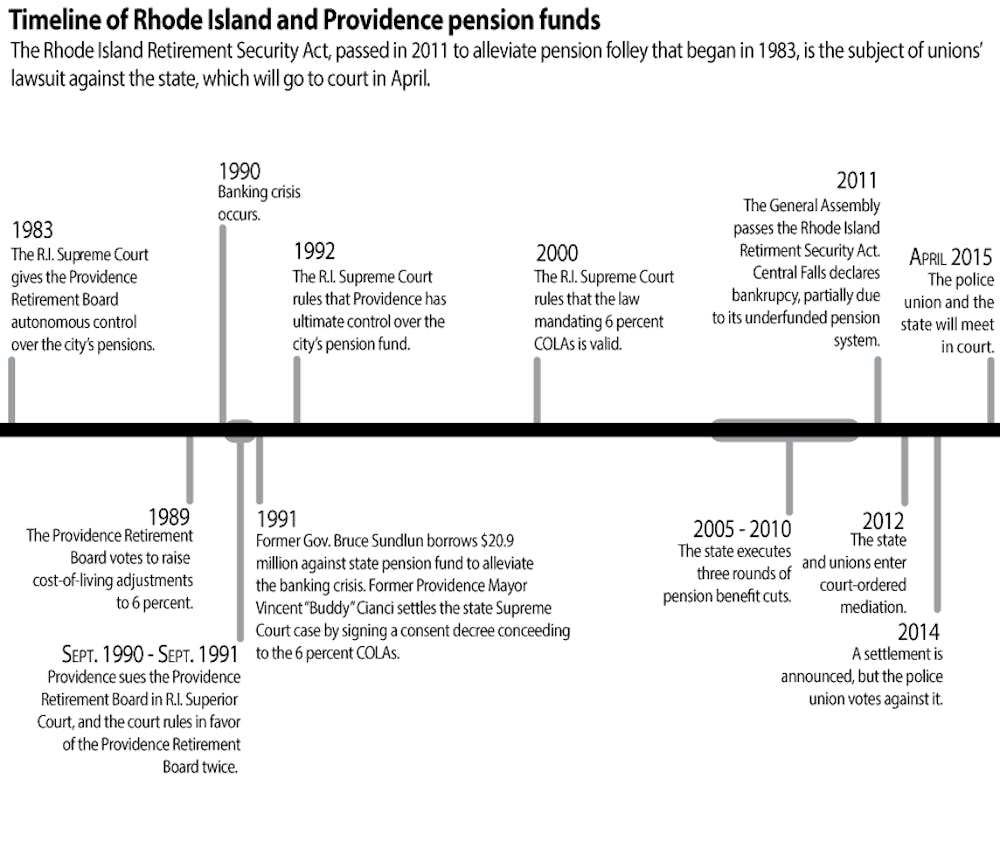

Unions representing public employees filed suit in the Rhode Island Superior Court in June 2012, questioning the constitutionality of the 2011 Rhode Island Retirement Security Act: The case is set to go before a jury this April.

The updated pension system transitioned all members of the state pension system from the traditional “defined-benefit” pension plan to a hybrid “defined-benefit, defined-contribution” plan.

The R.I. General Assembly passed RIRSA in 2011 to deal with the massive funding gap in the pension system.

Despite the fact that Rhode Island contributed the “recommended amount” to its pension fund between 2005 and 2010, the fund remained insufficient to meet the demand for pension benefits fully. For example, “the system was 49 percent funded in fiscal 2010 and faced a $7 billion funding gap,” the Pew Center on the States reported.

The state began to tackle its pension problem by executing three rounds of benefit cuts between 2005 and 2010, altogether reducing benefits by 23 percent, according to a report from the Economic Policy Institute.

Gov. Gina Raimondo, who was the state’s general treasurer at the time, led the effort to expose the pension system’s funding shortage publicly, releasing a report titled “Truth in Numbers” in May 2011.

The report revealed that unfunded liabilities — the discrepancy in pension funds — were between $6.8 and $9 billion, and taxpayer contributions to the pension fund were projected to be over $1 billion by fiscal year 2022.

Raimondo’s concerns were confirmed in August 2011, when Central Falls declared bankruptcy, partially due to its $80 million unfunded pension system.

Decades of instability

Rhode Island’s current pension crisis traces its roots back to 1983, when a R.I. Supreme Court decision gave the Providence Retirement Board autonomous control over the city’s pensions despite the fact that union members made up a majority of the board.

In December 1989, the board voted to raise cost-of-living adjustments — year-to-year increases in benefits — to 6 percent and increase retirement funds for police officers and firefighters by roughly more than three times their original amount. The adjustment in COLAs alone allowed pensions to double about every 12 years.

The city challenged the board’s newfound control in state Superior Court, only to lose twice. While the issue was pending in the state Supreme Court, then-Mayor Vincent “Buddy” Cianci — having just been elected with significant union support — settled the dispute. On Dec. 18, 1991, Cianci signed a consent decree that tied the city to the board’s changes for the pension system “in exchange for a few union concessions,” the Providence Journal reported. This consent decree prohibited the City Council from taking action on the pension system even after the state Supreme Court handed over the reins after the eventual resolution of the case in 1992.

In 2000, a state Supreme Court allowed high COLAs to continue for many pensioned employees.

“The financial impact was enormous — Providence’s unfunded pension liability more than doubled from $167 million to $412 million in a single year after the 1991 consent decree was established as legally binding,” WPRI reported.

Another disruption to the pension system occurred around the same time at the state level in 1991, when then-Governor Bruce Sundlun borrowed $20.9 million from the pension fund to alleviate financial damage caused by a 1990 state banking crisis. Sundlun also chose to defer annual required contributions to the pension plan for the next two years.

In 1993, the funding ratio for the state employees’ pension fund dipped to 72.6 percent, while the teachers’ fund was at 66.7 percent.

Funding ratios measure “how well-funded the pension plan is,” and are determined by private actuarial firms, said R.I. Auditor General Dennis Hoyle.

“They look at the information and … make an assumption as to when that person is likely to retire and how long they might live once they’re retired and collect the benefits,” he said.

Though funding ratios improved within the decade — climbing to 81.6 percent for state employees and 77.4 percent for teachers by 1999 — the state employees’ and teachers’ systems regressed to 56.3 percent and 55.4 percent, respectively, by 2005.

“Rhode Island’s pension liabilities grew 70 percent between 1999 and 2008, outpacing assets, which grew 25 percent in that period,” according to the Pew Center.

The state attempted to lessen its funding gap during this time period by raising the retirement age and restricting COLA increases for less-tenured public employees. When those measures proved insufficient, they turned to a solution that would drastically change the source of pension benefits: RIRSA.

An unwelcome change

The argument over RIRSA centers on the reduction of benefits, particularly the guaranteed welfare that “defined-benefit” pensions afford.

“Under a (defined-benefit pension), you’re guaranteed a certain benefit based on your years of service,” Hoyle said, adding that “the government funds that benefit regardless of specific investments.”

The new plan incorporates a “defined-contribution” aspect to the existing defined-benefit plan. In a defined-contribution pension, employees are required to contribute money to investments, and the result of their investments makes up their retirement fund.

“It’s like you had 100 dollars and invest in the stock market for 20 years,” Hoyle explained. “There’s no guarantee what it will be worth.”

“The value to the employee from a (defined-benefit) plan is you know how much you’re receiving and the risk of poor market performance is on the employer and not on you as the employee,” said Sam Zurier, city councilman and lawyer for the union in April’s pension trial. “Conversely … the state bears the risk of poor markets under defined benefit, and they’re relieved of that risk under defined contribution.”

“It transfers some of the risk to the employee, whereas before the employer was holding all the risk,” Hoyle said.

RIRSA also increased the retirement age from 62 to 67 and suspended COLAs until certain employee pension plans “reached a funded status of 80%,” according to the auditor general’s annual 2014 report.

The passage of RIRSA was designed to lower the state’s unfunded liability by $3 billion and save $274 million in taxes, according to the Pew Center and the Providence Journal, respectively.

Preparing for (legal) battle

The trial itself revolves around the constitutionality of RIRSA — whether the state has the right to alter retirement plans retroactively.

“One of the legal issues is when they passed the law with the COLAs and then they passed a law later on removing the COLAs, is that violating a contract?” Zurier asked. “Does the GA have the authority to change these terms without having to make up this money to the employees?”

“The unions want the cost-of-living adjustments restored,” Zurier said. “There’s a transition for some employees from a defined-benefit plan to a defined-contribution plan.”

The state and unions entered court-ordered mediation in December 2012. A settlement was announced in February 2014 that would give a one-time 2 percent increase to the first $25,000 of an employee’s pension, with a 3.5 percent increase every four years starting in 2017 and continuing until pension funding reached 80 percent.

But 61 percent of the police union members, who represent 1 percent of the total settlement voters, effectively ended mediation by voting against the settlement. The resulting jury trial will commence in April.

“The State continues to believe that the pension changes enacted by our General Assembly are constitutional and that the State has strong legal arguments to support its positions,” Shana Autiello, director of communications for the general treasurer, wrote in an email to the Herald. “The State’s legal positions in the litigation … will be a matter of public record.”

“I cannot speak for the state, but I would observe that the factual findings in some of the earlier rulings that the judge made were going against the state,” Zurier said. The state unsuccessfully asked presiding Judge Sarah Taft-Carter to recuse herself from the case, claiming she had personal stakes in the outcome.

“There are actually four different cases,” Zurier said. They include state employees and teachers, municipal employees, retired employees and firefighters and policemen.

The nature of the trial means that no end date can be pinpointed, Zurier said, adding that “if (the cases are) tried back-to-back-to-back-to-back, it could be a very long time.”

Even after the proceedings end, the chance of appeal to the R.I. Supreme Court is very high, WPRI reported. An appeal process through the state Supreme Court could take one to two years, Zurier said.

There are “billions of dollars” involved in this “high-stakes” case, Zurier said. “You want to exhaust all your chances before accepting an unfavorable result.”

But settlement is not necessarily out of the question, Zurier added. “There are so many moving parts to this case that it makes more sense to settle it, if at all possible.”