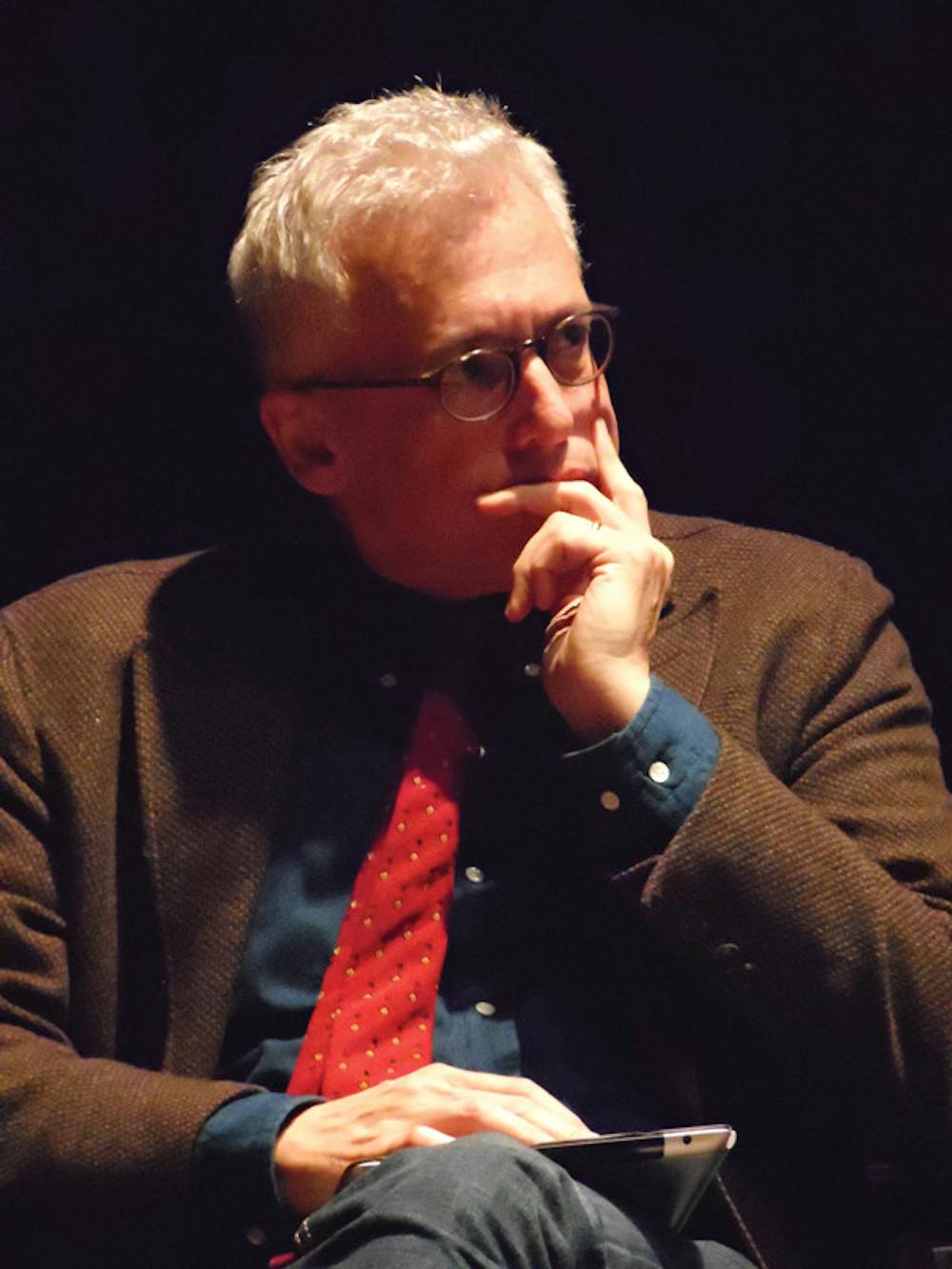

Donald Margulies did not always cast himself in the role of a dramatist. Now a prolific playwright and adjunct professor of English and theater studies at Yale, he graduated with a BFA in visual arts. Since taking up the pen, he’s received a slew of accolades, including the 2000 Pulitzer Prize in Drama for “Dinner with Friends,” that has projected him to center stage. But for all his acclaim, Margulies described himself as a “Brooklyn boy” during his Thursday lecture — the inaugural installment of the Department of Literary Arts’ Levin Family Lecture Series. Prior to his lecture, Margulies sat down with The Herald to talk about his inner visual artist, his love-hate relationship with Hollywood and Jason Segel’s upcoming role as David Foster Wallace.

Herald: What brings you here to Providence tonight? What do you plan to discuss and hope the audience will retain from the event?

Margulies: I’m here to inaugurate the Levin Family Lecture Series, which was endowed by a friend of mine, Glenn Levin, and his family. The purpose of it is to bring working creative artists to Brown to discuss the work that they do. I’m very delighted that I am the first in what I hope will be an enriching series, and I’m really here to talk about the life and craft of playwriting, and share with the audience some clips, anecdotes and readings from one or two of my plays.

You have some background in visual arts. How does that influence your playwriting?

I have always been a visually-oriented person, and my plays come from different places. But sometimes they do come from images or dreams, and I very often have a specific idea of how things should look on stage, which I guess is part of my visual arts bent. It serves me well. It gives me a certain vocabulary to share with designers on various productions. I don’t design my shows, but I certainly collaborate with the designers … and I’ve been very thrilled to have had a career of working with designers who are very receptive to that kind of input.

You have had a handful of works that were originally written for the stage, but were then adapted for the screen. How did that transformation happen?

Well, one of the great secrets of surviving in theater is that you subsidize the life in the theater by being a writer-for-hire in film and television. So I’ve been doing that for many years. I’ve survived on screenplays for which I was paid, but which will never be made because that is the nature of film development in Hollywood at this time.

There are a couple of my plays that have been adapted to television: “Dinner With Friends” was made into a HBO movie, and “Collected Stories” was a PBS special. I have certain misgivings about those productions, but the text for each of those is mine. The way that they are rendered is something I may quibble with, but at least these are my words, and I am delighted to have some sort of visual record of the work. Otherwise, theater is such an ephemeral enterprise. Just knowing that there’s even some vestige of what it was on stage captured on film is some kind of comfort to me.

Could you tell us about some current projects you’re working on?

I have a play on Broadway right now called “The Country House,” which ends its run on Nov. 23. I’ve written a film called the “End of the Tour,” which stars Jason Segel and Jesse Eisenberg — Segel plays David Foster Wallace — that will be released in 2015, which I’m very proud of and excited to see released.

You teach English and theater studies at Yale. What do you aspire to teach your students?

In my fall seminar, I have them read my favorite plays — plays that I learned a lot from as I was coming of age as a playwright in the ’70s and ’80s. Through my teaching of works that inspired me, what I can hope to do with my students is at least show them the roots of inspiration, because I don’t think you can really teach writing. I think you can teach inspiration. You can teach young people how to identify what inspires them, and I think that’s the best lesson I can bestow on my students.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

A previous version of this article misspelled the name of Glenn Levin ’80. The Herald regrets the error.

ADVERTISEMENT