As registration for spring semester courses approaches and students plan their academic futures, those in some concentrations face an additional choice: A.B. or Sc.B.?

Those interested in studying applied mathematics, astronomy, astrophysics, biology, chemistry, cognitive science, computer science, engineering, environmental studies or science, geological sciences, mathematics, physics or psychology have both degree options available to them.

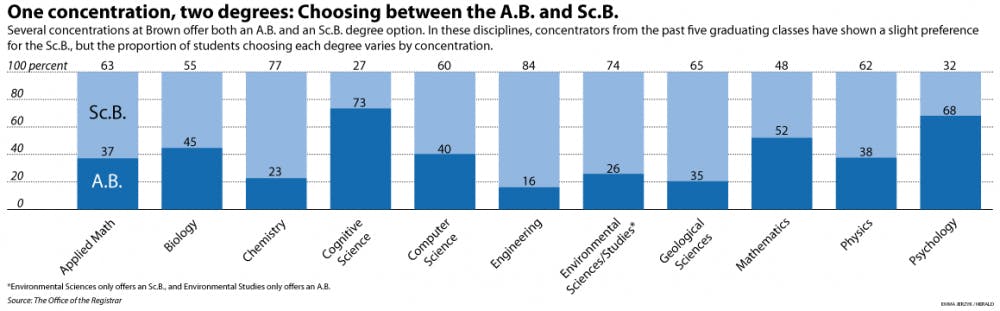

Within these concentrations, the science degree choice has proven slightly more popular, with 56.3 percent of graduates in the last five years selecting Sc.B. tracks within them.

Decision

The most obvious difference between the A.B. and Sc.B. degree is the number of courses required: Sc.B.s require up to twice as many courses as A.B.s, and students must often complete independent research or a senior thesis project.

“The Sc.B. is a more serious involvement in the subject,” said Richard Schwartz, professor of mathematics and mathematics concentration adviser. “The A.B. is a lighter involvement in the subject and is more compatible with doing other things.”

The A.B. degree offers more flexibility, which can be appealing to double-concentrators and students who want to study abroad, said Richard Bungiro PhD’99, senior lecturer in molecular microbiology and immunology and a biology concentration adviser.

While it is not unheard of to double-concentrate while pursuing an Sc.B., it is more difficult and requires careful planning, multiple professors said, adding that doing so may require completing a fifth year.

The lighter load of the A.B. also provides students who add a concentration in their sophomore or junior year a more manageable way to fulfill concentration requirements, several professors said.

The A.B.’s flexibility can actually allow students to pursue one area in greater depth. For example, in computer science, some students choose to pursue the A.B. degree in order to work on research, publish papers or simply focus on studying one area of computer science, rather than fulfilling the broader requirements of the Sc.B., said Professor of Computer Science Shriram Krishnamurthi.

But some students choose Sc.B. degrees precisely because of the more extensive requirements. “If you want to do research, you kind of have to know all the upper-level chem material,” said MinJung Han ’16, who is pursuing an Sc.B. in chemistry. “If I’m going to take all that anyway, I might as well get an Sc.B.”

What you make of it

Among some students, there is a perception that the Sc.B. is “more impressive and more rigorous,” said Sarah Taylor, an instructional coordinator and science learning specialist at the Science Center.

After the health and human biology concentration became exclusively an A.B. program in 2013, enrollment dropped, perhaps due to student perceptions that an A.B. was inferior, Taylor said.

Bungiro said some students he works with are attracted to the Sc.B. because they are “enamored of titles and names,” and that he advises these students to consider whether pursuing the Sc.B. would actually be beneficial to their future work.

Michael Greenberg ’07, who graduated with two A.B. degrees — one in computer science and one in Egyptology — said he initially planned to pursue an Sc.B. in computer science. “I sort of assumed I would get the harder one,” he said. But his opinion changed: “I remember sitting down and looking at the actual requirements and being like, ‘This is ridiculous. I just don’t care enough.’ And it wasn’t clear to me what (the Sc.B.) got you other than some sort of macho cred.”

Across a variety of departments, students and professors repeatedly voiced the idea that the name of the degree itself matters far less than the work students pursue as undergraduates.

The effort a student puts into doing research and forming relationships with faculty members is ultimately just as important as which degree is pursued, said Bungiro. “In the end, I don’t think it’s a predictor of one’s success, it’s just a part of the larger picture.”

In fact, many colleges, including top liberal arts schools and several Ivies, do not even offer a separate Sc.B. degree in concentrations outside of engineering.

Out of the gates

Students planning to apply to graduate programs in the sciences often select the Sc.B. degree option, which may be the smart choice, many professors said. Engineering graduate schools, for example, strongly prefer an Sc.B., said Iris Bahar, professor of engineering and chair of the engineering concentration committee.

This is also true of math, Schwartz said. Though it is possible for A.B. students to go to graduate school, it is significantly harder to get into top programs, he added.

But for many concentrations, an Sc.B. proves advantageous only because of the courses and research it requires, rather than the name of the degree itself.

Krishnamurthi, who also acts as the director for graduate studies in the Department of Computer Science, said he pays more attention to applicants’ courses, recommendations and research experience than to the degree they received.

“I can’t tell that it’s made a difference in anything,” Greenberg said of his A.B. “I got accepted to my top PhD school and went there and now I’m a post-doc, and nobody ever asked any questions.”

The A.B. degree is “not a detriment. It’s not a second-rate degree,” said Professor of Geological Sciences Jan Tullis.

Regardless of whether students are pursuing an A.B. or Sc.B. degree, Tullis said she always encourages concentrators to do research. “That’s how you find out whether you actually love doing science, or whether you just love reading about it,” she said. No matter what the student ends up doing, that experience is beneficial, she said.

Professor of Physics Robert Pelcovits, a concentration adviser, said he encourages physics A.B. students who are interested in going to graduate school to do what he terms an “A.B. plus,” which includes additional upper-level courses and, ideally, a senior thesis.

The situation is generally similar in the job market, said multiple professors across disciplines. Though an Sc.B. degree can help, it is only one of many factors considered.

The one major exception is engineering, due to the importance of having one’s degree accredited by ABET — an independent organization that reviews the quality of colleges’ engineering programs. An accredited degree is often very important or even required by employers, Bahar said. While Brown’s Sc.B. engineering programs are accredited, the A.B. is not. “You have to give up something if you want the extra flexibility” of an A.B., she said.

“Often times, a student who gets a bachelor of arts in engineering is someone who wants to get that experience in technical problem-solving but then apply it to other areas,” such as consulting, science education or industrial design, Bahar said.

For those interested in careers that involve multiple fields, pursuing interdisciplinary coursework may be more beneficial than going deeper into one subject through an Sc.B. In computer graphics, for example, “It might be just as valuable for you to have that one extra course in art as it is to have the one extra course in computer science, or maybe more valuable,” Krishnamurthi said.

A balance to be struck

Multiple students navigating the different degree options said in deciding between degrees, it is critical to get others’ input.

Talk to professors and older students, advised Mikala Murad ’16, an Sc.B. concentrator in psychology.

Students must find a balance between depth and exploration, professors said.

“Don’t think about the future all the time,” said Tullis. “Think about what you’re learning now” and enjoy all that Brown has to offer, she said. “I’m a strong believer in Brown’s liberal arts education.”

Professors said they stand by all of Brown’s degrees. “We don’t think any of our degrees are somehow weak degrees or sort of an embarrassment, because if we did, we would fix them,” Krishnamurthi said.

ADVERTISEMENT

More