“Graphic Design: Now in Production,” the Rhode Island School of Design Museum’s latest exhibition, is by any measure an ambitious project. Co-organized by Minneapolis’ Walker Art Center and the Smithsonian’s Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum in New York, the exhibition aims to demonstrate the breadth and depth of contemporary work in graphic design.

Showing now in the Chace Center, the works are divided into printed materials like posters, periodicals, books, informational design pieces and television titles. The first room tackles two of the most iconic forms of graphic design: posters — some presented independently, others in a series — and books, arranged in glass display cases.

The exhibit circles relentlessly around the interaction of form and content, establishing but sometimes clouding meaning.

Anthony Burrill’s poster “Oil & Water Do Not Mix” is a compelling inclusion. On the top two rows, the words “Oil & Water” appear dark yellow against a white background, whereas on the bottom two rows, “Do Not Mix” is white against a dark yellow background color. The page is divided by a squiggly line representing water. The content of the poster is articulated visually, almost before one reads the words themselves. Upon closer examination the viewer learns the piece is “printed with silkscreen ink made from oil spilled in the 2010 Gulf of Mexico,” according to the exhibition text.

But form can also elude and even deny content. “Felt-Tip Prints” by Daniel Eatock counters Burrill’s work by asking “whether a poster needs to have a message at all,” according to the exhibition text. The work comprises four posters, each white with droplets of inks of various colors scattered across the papers. In front of these posters is a sheet of white paper balanced on tips of several felt-markers. Despite the supposed lack of message, it is still fascinating to see the work both in progress and finished.

If the first room houses some of the more iconic forms of graphic design, the next room spotlights the discipline’s expansion into varied forms and more interactive objects.

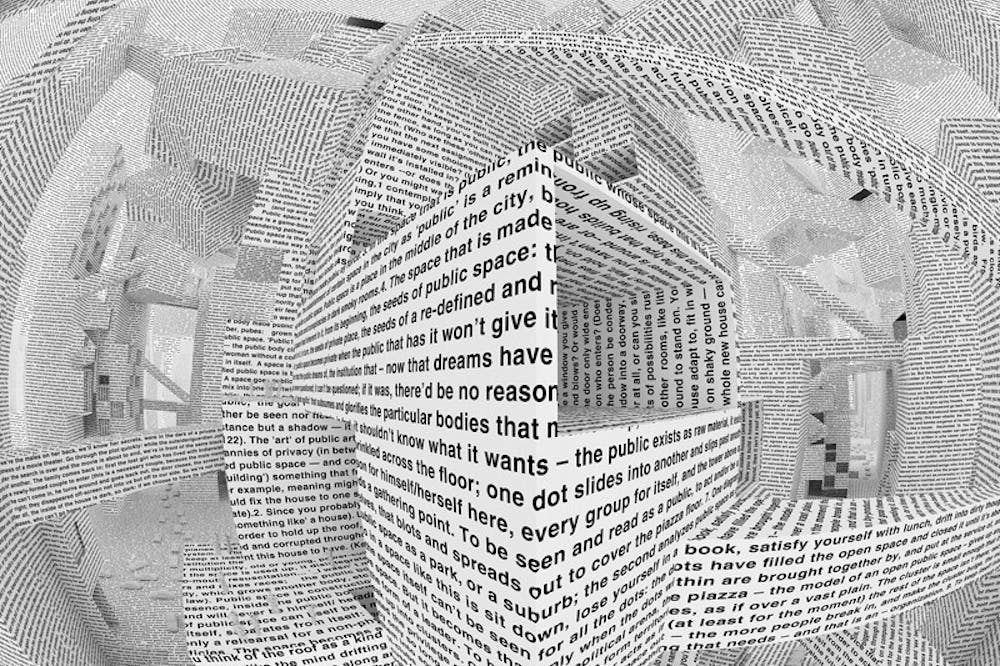

“On the Origin of Species: The Preservation of Favoured Traces” by Ben Fry demonstrates how, contrary to the popular belief that scientific ideas remain fixed, Darwin’s famed text changed throughout its publishing history, according to the exhibition text. A printed version of the entire “Origin of Species” hangs on the wall, legible only as color-coded blocks of text. A computer allows visitors to track Darwin’s progress toward a final version.

In some cases the museum space inhibits experiencing some of the more interactive objects, notably Fry’s redesign of Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein.” An open copy of the book reveals that the text has been stylized using a variety of formats. The overt inconsistency in the letter forms, according to the exhibit text, does have a logic: “The most common characters are employed at the beginning of the book, and the text devolves into less common, more grotesque shapes and forms toward the end.” It may have been more effective if one could pick up the book and witness that transformation across the pages.

Certainly some pieces in the collection stand out, but the real revelation is how much color, typography, images and symbols structure lived experiences. It’s a bit overwhelming to accommodate the entire “evolution of graphic design” in a single exhibition, so to fully enjoy the exhibit, leave ample time.

There will be a two-part discussion with the co-curators of the exhibition, Andrew Blauvelt and Ellen Lupton, April 16. Another event April 17 will allow visitors to meet some of the featured designers.

ADVERTISEMENT