She braids her hair. Brushes her teeth. Gently reminds her husband that it is his birthday. She hands him a pair of enormous, fuzzy slippers in the shape of ducks, which he slides on his feet, quacking. He pulls on a pair of gloves — boxing gloves, to be precise — and sets to work.

These are the opening moments of “Cutie and the Boxer,” the Oscar-nominated documentary that follows the careers of Ushio Shinohara, a Japanese neo-dadaist artist, and his wife, Noriko, who also pursues her own art throughout the film. The film, which screened Thursday night as part of the Ivy Film Festival, traces their 40-year marriage, which developed alongside their art.

Director Zach Heinzerling offers a sensitive, intimate portrait of the artists, infiltrating their most private moments without approaching voyeurism. It is compiled from a series of in-the-moment shots recounting the Shinoharas’ daily lives, forgoing the formal interviews that are so often the preferred fare of documentary filmmakers.

The film occasionally resorts to found footage, showing a spiky-haired, pugnacious Ushio at the height of his ego. There is a dark parallel between this man who flies into hysterics at the uncertainty of his art and the present-day man who tears up at a failed canvas he can’t determine “good or bad or finished or unfinished.”

“Art is messy and dirty when it pours out of you,” Ushio howls in one such vintage clip, summing up his complicated relationship with both his wife and his work.

“Cutie and the Boxer” derives its name from the affectionate appellations for each of its main characters. Ushio earned the mantle of “the boxer” due to his unique painting style, a sort of spontaneous, Pollock-like attack of the canvas with boxing gloves smothered in paint. During a question-and-answer session that followed the film screening, Ushio, whose remarks were translated by Yukiko Watanabe ’16, described how he came to paint through boxing: In the 1960s, “action painting” was very popular. It was “quick, beautiful, rhythmical” — the three traits Ushio said he admired most.

“I wouldn’t do it if it weren’t for an audience,” he added.

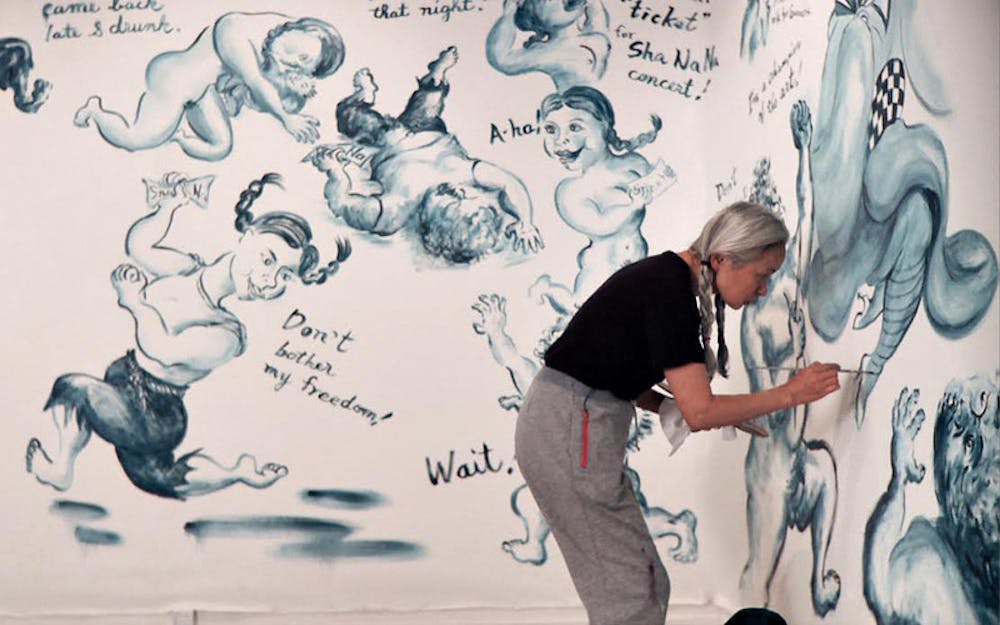

Noriko paints a cartoon character named “Cutie,” whose exploits mirror her own story of love and heartbreak as she migrates from Japan to the United States in search of artistic recognition and a brighter future.

The Shinoharas confront roadblocks as they struggle to make a living in the crowded, competitive New York City art scene with curators, artists and dealers all competing for a claim on the canon. This is never more evident than when a curator from the Guggenheim comes to examine Ushio’s work, declaring a search for a piece with “history.” Unfortunately, the only piece that fits the bill was already drunkenly promised to a friend of Ushio’s — just another missed opportunity in a string of disappointments fostered by personality and circumstance.

While Ushio’s career flounders — he is acclaimed for his avant-garde work but fails to make sufficient sales to support the family — Noriko begins to find her own voice. At the outset, Cutie seems to be a mechanism for Noriko to come to terms with her shattered dreams: She marries Ushio because she has become pregnant, and he promises to love her and support her career.

At one point in the film, Noriko proclaims she has lost her joy in painting. And during the Q&A following the film, one audience member asked how she regained her inspiration. “Time,” she responded.

“Everything was so missing, so ruined, so devastating, so the only thing I could have was art,” she said.

But her animation eventually serves to bring Noriko her own recognition. One gallery owner requests to exhibit her work in tandem with Ushio’s, and she paints a sparse mural of “big Cuties.”

“I feel so free when you’re not around,” Noriko confesses to Ushio in one scene, shortly after she has begun work on her mural. This is a quintessential manifestation of their relationship: On the one hand, theirs is a marriage of partnership, of symbiosis, but on the other hand, Ushio’s career often takes priority, and his outsized personality tends to smother his more reserved wife. It is only when she absorbs herself in her own art — independent of Ushio’s domineering hand — that she can truly express herself.

The question-and-answer session featuring the Shinoharas and Heinzerling — moderated by Nathan Lee GS, a PhD student in Modern Culture and Media and former critic for the New York Times and the Village Voice — took place in MacMillan 117. While Ushio’s responses were translated, Noriko spoke in English throughout. The three spoke about the dynamics of the filmmaking process, in terms both of the technical production and their constantly evolving relationship.

“The fact that Zach is an American and he couldn’t speak Japanese is why we could be so open about our personal lives,” Ushio said as Watanabe translated.

“A lot of the scenes, I would just shoot and not have any idea what they were saying,” Heinzerling added.

Ushio said he was initially disappointed by the final product that was the film. “My art was being praised, but gradually the focus shifted to Noriko’s artworks,” he said. “And in the end, I get beaten up by her with the boxing gloves.”

But eventually he realized Noriko loves him, he said.

“It took the film,” Noriko added playfully. The audience broke into laughter. Throughout the discussion, Ushio and Noriko would grab the microphone out of each other’s hands, each vying for the audience’s attention.

In response to a question about how their relationship evolved over the lifetime of the film, Ushio recounted a Missouri screening for an audience of 1,500 where the film received a standing ovation.

“I felt like I was Matsui in Yankees,” he said. “That’s when I felt the power of films.”

ADVERTISEMENT