The life and work of Nazim Hikmet, the most prolific, influential poet of modern Turkey, were honored Tuesday in a conference hosted by the Middle East Studies Initiative at the Watson Institute for International Studies. The conference, largely the brainchild of Professor of English Mutlu Blasing, brought together some of the world’s leading experts of Turkish poetry.

“We are very fortunate that Professor Blasing put this conference together, for it is the first one of its kind in the United States,” wrote Beshara Doumani, professor of modern Middle East history and director of Middle East Studies, in an email to The Herald. He described Blasing as the world’s leading authority on Hikmet. “Middle East Studies tries to focus the passions of its faculty around programming and initiatives that speak to the issues of our time,” he wrote.

Hikmet, who lived from 1902 to 1963, was incredibly controversial in his time. He was imprisoned for 13 years in his native Turkey and later exiled to the Soviet Union for 13 more. But during this time “he produced a body of work whose scope and power affirm the ultimate triumph of the human spirit over the forces of tyranny,” according to the event website.

Hikmet’s work was a powerful voice for self-determination in a region undergoing political transformation. His words, recorded in Turkey’s recently reformed written language, demonstrated Turkish solidarity amid national strife.

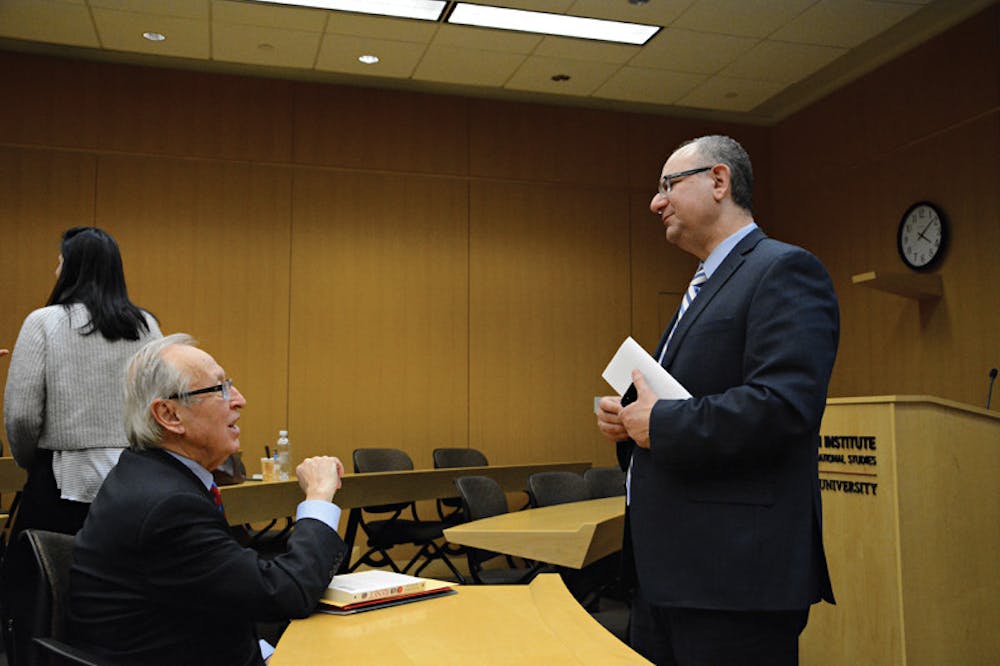

Stephen Kinzer, a former foreign correspondent for the New York Times and current visiting fellow of International Studies, was one of the speakers at the conference. Kinzer, who has written extensively on Hikmet, spoke about the ramifications of his work on Turkish nationalism.

“His poems reflect a great passion for life and also fervent patriotism at a time when the Republic of Turkey was being shaped,” Kinzer wrote in an email to The Herald. “In different ways, he was comparable to Pablo Neruda, Federico Garcia Lorca or Bertolt Brecht.”

Robyn Creswell, assistant professor of comparative literature, spoke of how Hikmet’s stylistic identity as a writer has reached an international scale due in part to translations of his work appearing in over 50 languages. Creswell’s talk focused on the multinational circulation of Hikmet’s texts despite censorship and political turmoil in the region. Hikmet traveled to Cuba, Beirut and Cairo, where his work was disseminated and quickly earned respect. Creswell himself translated the original Arabic texts to English for the colloquium.

“He’s more of a legend than a body of texts,” Creswell told The Herald. “He represents a moment when politics and poetry were combined, back when it was possible to combine them.”

Despite his international recognition, Hikmet remains relatively unknown to American audiences compared to other politically-driven writers of the same time period.

“Our conference was another step toward giving this huge figure the exposure he deserves in this country,” Kinzer wrote.

The conference was also presented online as a telecast, which allowed the diverse speakers to reach the wider audience of Hikmet admirers and supporters, Doumani wrote.

“The questions of ‘commitment’ in literature and knowledge production is a central one to the intellectual like of Brown and the world at large,” he wrote. “Nazim Hikmet’s life and work speak to the possibilities and tragedies of commitment to art and social change.”

A previous version of this article misidentified the experts who attended a conference Tuesday. They were scholars of Turkish poetry, not Arabic poetry. The Herald regrets the error.

ADVERTISEMENT