A recent study co-led by Professor of Neurology Stephen Salloway found that bapineuzumab, a drug previously thought to slow the effects of Alzheimer’s disease, causes no improvement in patients’ memories or daily functioning.

The primary clinical results were “disappointing” because positive results from the drug “would have propelled the field forward at a much greater rate and given much more optimism for Alzheimer’s as a treatable disease,” Salloway said.

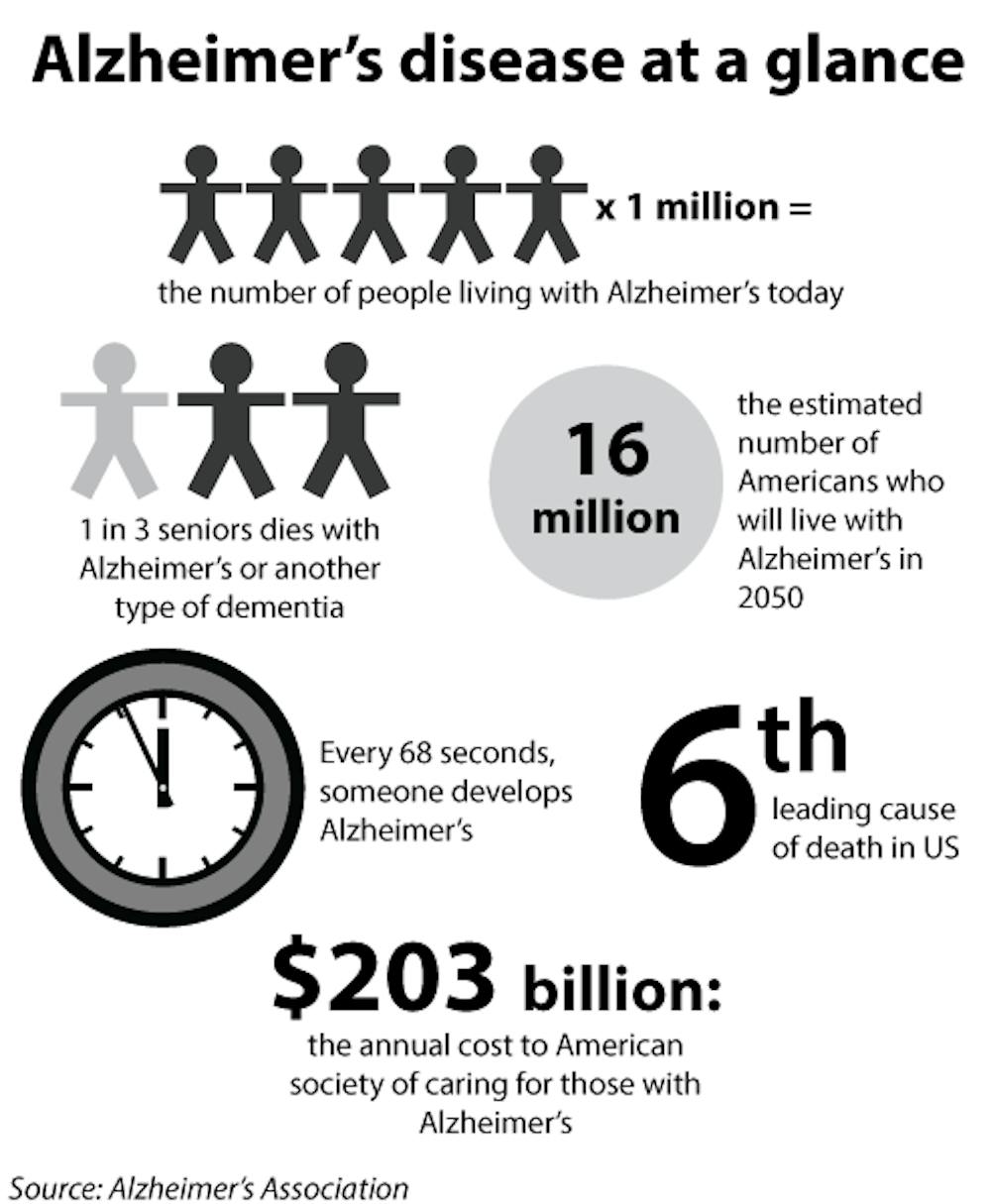

Alzheimer’s disease currently affects over five million people in the United States, but it remains without a cure or method of permanently delaying its effects.

The results of the trial were published in the New England Journal of Medicine Jan. 23.

The study, which tested patients aged 50 to 88, showed no significant differences in clinical outcomes between patients given bapineuzumab and those given a placebo. Despite the negative clinical result, the researchers determined patients given the drug had reduced beta-amyloid protein buildup, Salloway said.

Alzheimer’s is distinguished by a buildup of beta-amyloid and tau proteins in the nervous system, which causes nerve cell breakdown, Salloway said. Bapineuzumab functions as an antibody that breaks down the buildup of amyloid protein in plaques, he added. The study indicated that bapineuzumab is associated with lower amyloid buildup in patients carrying the APOE ε4 gene, which is associated with increased likelihood of developing the disease.

Craig Atwood, research director of the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Institute at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, said the study’s focus on an immunological vaccination as a strategy for treatment was misguided. Past research has documented the negative side effects of destroying amyloid plaques, he said.

“I hope that this paper will lead researchers to start looking at other avenues to identify the underlying disease mechanisms,” Atwood added.

The researchers also discovered that PET scans, a type of brain imaging, can detect a patient’s amyloid plaque buildup, which is beneficial for early detection of Alzheimer’s, Salloway said.

Alzheimer’s has a “long, silent pre-clinical phase,” during which the disease is hard to detect, Salloway said. Scientists are looking to detect and arrest amyloid buildup early in the process, he added.

Alzheimer’s should be viewed as a “major public health problem,” Salloway said. Over the next 15 years, there are projected to be 77 million baby boomers turning 65, which is the beginning of the “risk state” for the disease, he added. These numbers translate into a significant increase in the time and money involved in caring for those who develop the disease, Salloway said.

“It’s like a tidal wave we’re facing,” he added.

Professor of Neurology and dementia researcher Brian Ott, who was not involved in the study, echoed Salloway’s dissatisfaction with the experiment’s results.

“I think that the results of these two clinical programs were disappointing to the Alzheimer’s research community and heightened concerns about the potential efficacy of passive immunotherapy as an approach to slowing progression in (Alzheimer’s),” Ott wrote in an email to The Herald. Moving forward, researchers at Rhode Island Hospital are exploring new avenues for Alzheimer’s research, he added.

The U.S. Congress and the Group of Eight — an international forum made up of eight of the world’s leading economic powers — have each designated finding drugs to delay the effects of Alzheimer’s by 2025 as a top priority, Salloway said.

Since the clinical study yielded negative results, Salloway said he ultimately envisions a cure for Alzheimer’s as a “cocktail drug” composed of several individual drugs that each attack the onset of the disease at different points.

ADVERTISEMENT