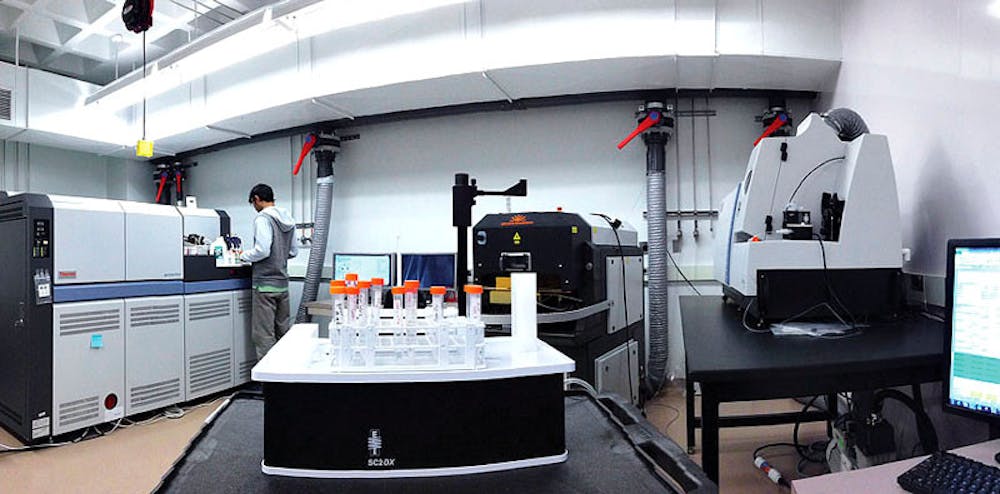

In a small room in the Geological Sciences building — where it is about 70 degrees Farenheight and 55 percent humidity — resides the University’s two plasma mass spectrometers. The larger of the contraptions measures the isotope, or the structure of an element, according to its atomic mass and the number of neutrons it contains, while the smaller one measures the concentration of elements in a material, said Alberto Saal, associate professor of geological sciences.

The mass spectrometers originally cost around $1.2 million. Saal arranged for the University to match funds he raised from donors, finally succeeding in bringing the machines to campus last year. Though they underwent months of installation, they can now be used by the public for a fee.

Brown’s two spectrometers are the only ones in the state.

Both devices use plasma to ionize the elements, creating charged particles that travel through an electric field.

“You bring the elements to such a high temperature in the plasma that it’s easy to ionize,” Saal said.

The room also features a laser, which dissolves the material into a solution before it can be passed through the machine, Saal said.

Kei Shimizu GS, a graduate student in the department of geological sciences, said he uses the machine to investigate the properties of rocks at the bottom of the ocean. The mass spectrometer can detect even elements that are present in very low concentrations as well as their isotopic compositions, he said.

The mass spectrometer is important to “understand what kind of different compositions there are in the mantle,” he added.

The mass spectrometers can be used to date rocks, as well as trace their origins, Saal said.

“Rocks from the moon have the same isotopes as those from Earth, so Earth and the moon come form the same origin,” he added.

Shimizu said he has found the machines very user-friendly.

“The hardest part is dissolving the rocks and purifying the elements without contamination,” he said. “Once we have the dissolved samples, the process after that is pretty simple.”

Shimizu said the University’s mass spectrometers incorporate the newest technology and require much less effort to analyze substances than older versions of the machine.

They also generate more accurate and precise data, Saal said.

Saal added that the machines have diverse uses. They can detect dangerous substances such as tiny traces of lead in paint or platinum group elements that produce defects in fetuses. The mass spectrometers can also examine archeological material and environmental samples that shed light on climate change and can be used for research in fields including chemistry, biochemistry and geochemistry, Saal said.

The mass spectrometer can be used to detect the source of lead poisoning by analyzing the isotope and tracing its origin, Shimizu said.

“We can pinpoint exactly what company is creating the pollution,” Saal said.

“For Brown it’s a great thing that a lot of other institutions are acknowledging us for allowing them to collect the data,” Shimizu said, adding that professors from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology visit campus to use the machines.

Saal said the machines are important for Brown as a whole, offering students accessible research opportunities at a “top-level capacity.”

ADVERTISEMENT