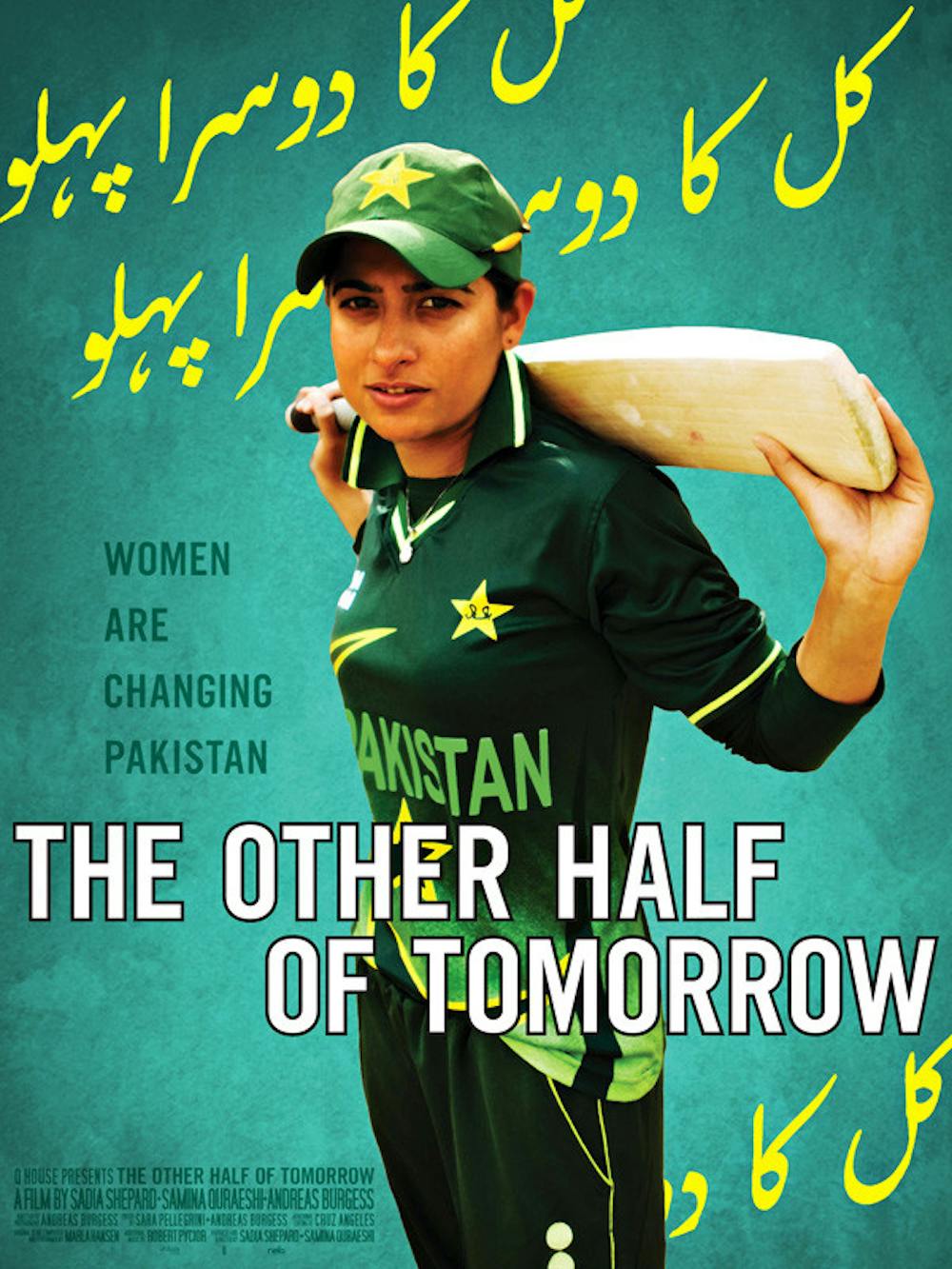

In her recent film “The Other Half of Tomorrow,” author and director Sadia Shepard examines the lives of Pakistani women determined to foster change in their homeland. In advance of her Nov. 6 appearance at Brown for the screening of her film, Shepard spoke to The Herald about her experiences making the movie — working with a range of collaborators, exploring the lives of Pakistani women and gaining a new perspective first-hand.

The Herald: You clearly made a point to draw from a variety of different fields of cultural expression and empowerment in choosing which women to portray in the documentary. What drew you to these individual women?

When my team and I began the casting process, we knew that one of our goals was to try and give some sense of the breadth and diversity of women’s experiences in Pakistan. … With 10 or 12 short portraits, you’re never going to be able to tell the story of an entire country, but we hoped that with our selections, we might be able to give you a glimpse of the range.

So we spent three months on the ground in Pakistan traveling all over the country and meeting with women leaders, educators, politicians, activists, non-governmental workers, health workers, artists, and began to … ask them what they thought that the main issues that women are engaging with in Pakistan in order to try and make Pakistan work better. …Some of those were maternal health, women’s education and empowerment, creative expression, political engagement, security and a safer Pakistan. …

It was a combination of trying to identify issues that we could then find protagonists that would help us to represent those issues and working with organizations that would help us identify people that we should work with.

You’ve discussed in previous talks how there are many cultural voices present in Pakistan, despite the perception that it’s a hegemonic culture. What different perspectives would you say you were trying to capture?

We, in the United States, tend to see Pakistan through a national security lens, and … parts of the culture that don’t fit into some of our prescribed notions about what it means to be Pakistani and what it means to be a Pakistani woman don’t always get told.

Pakistan is an incredibly complex and often contradictory place. This is a country that has had a female prime minister, but also activists in Pakistan are fighting draconian rape laws. … So how do you try and represent that kind of diversity, even within a single family, was one of our challenges.

We quickly realized that it would be, we felt, impossible to make a single film. … There was no one single story.

What was the process of contacting, interviewing and working with each woman like?

The film’s aim was to prioritize women telling their stories in their own words, and the process with each one was we would spend as much time as we could kind of getting to know each person spending time with them, seeing how their daily life worked, who are the major players in each of their lives, and get to know their families and colleagues. That would then help us to figure out how to anticipate what the story might look like and how we might want to tell it.

What links did you see or try to show between these different perspectives coming from very different places, as you continued with the interviews?

What all of the women in “The Other Half of Tomorrow” have in common is a deep love for their country and a strong sense that things are only going to get better with their active and personal engagement in creating social change. These are women from … different socioeconomic and social backgrounds, but who are united in this feeling that “something has to change and it begins with me.” And that was something that was enormously … surprising and often very inspiring ... — most of them, of course, didn’t know each other, but there was somehow this sort of strong core of social responsibility that was linking them all. …

Each one of the female protagonists … has supportive men in their lives — fathers, brothers, husbands, uncles — who have supported and encouraged these women to pursue their goals and to fight for something better. And that went against I think many of our preconceived notions about pervasive stereotypes regarding both Pakistani women and Pakistani men.

You mentioned on your website that your mother, artist and author Samina Quraeshi, and husband, cinematographer Andreas Burgess, were very heavily involved in the project. How has working with your family influenced the creative process?

Because Pakistan is so difficult for foreigners to travel to right now, it’s a place where you do find a fair number of Western print journalists … but there are not a lot of documentary filmmakers from the West. …

Samina Quraeshi, my late mother, was a Pakistani-American artist and author and was someone who spoke multiple South Asian languages. (She) was able to best explain the mission of our project and why we wanted to do it. So suddenly we were recognizable as a family unit, and then we were welcomed as you might welcome a family of friends to your home.

That was pretty universally our experience, and we were enormously fortunate. ... Pakistanis are famously hospitable, and we were lucky to make some great friends in the process.

ADVERTISEMENT