In late 19th- and early 20th-century Providence, the highest honor was to be invited to tea at singer Sissieretta Jones’ house on College Hill, said former state Rep. Ray Rickman.

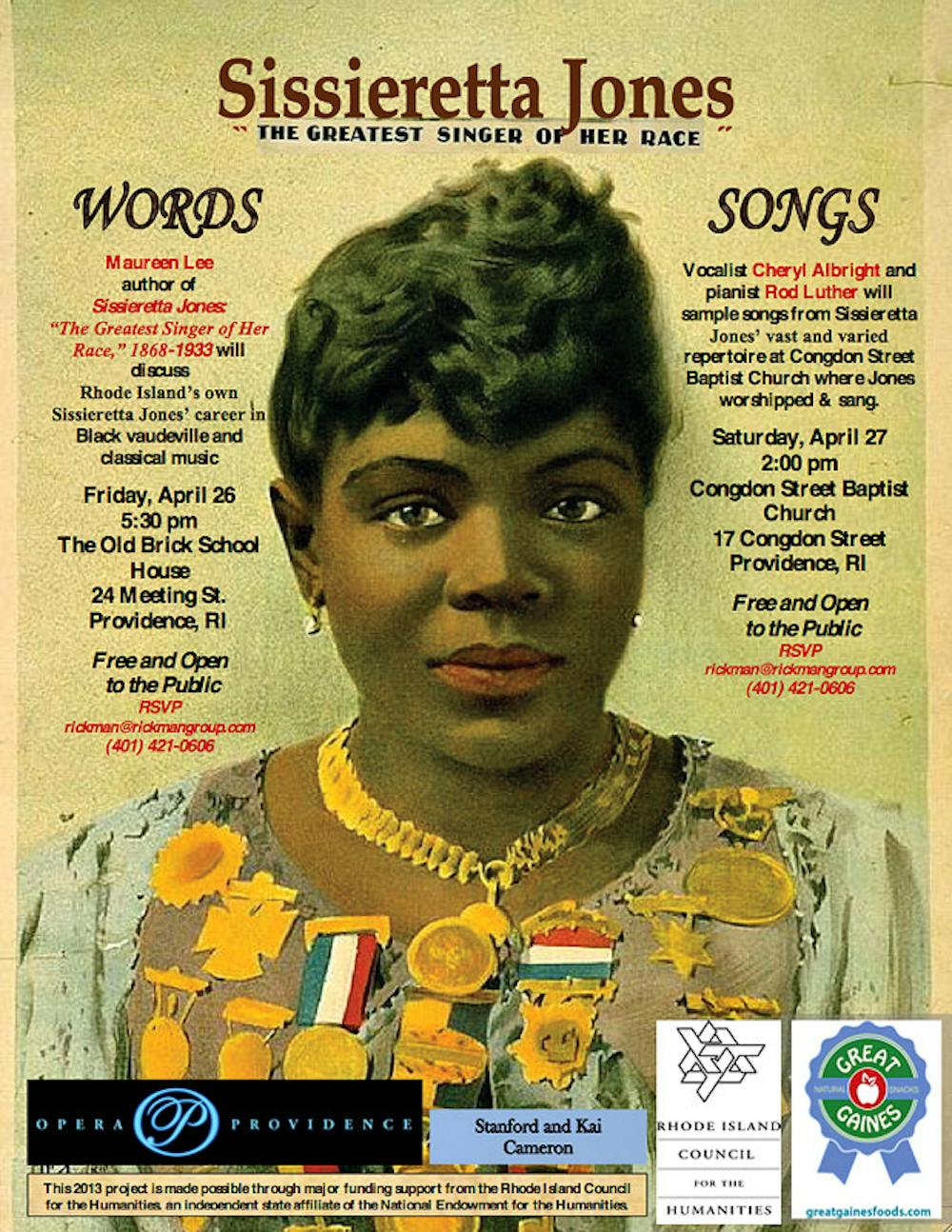

Along with public scholar Robb Dimmick, Rickman is co-directing an event later the month that will honor the life and career of this once-famous singer. The event, which includes a talk about Jones April 26 and a concert featuring her music April 27, is organized by the Rhode Island Black Heritage Society and sponsored by the Rhode Island Council for the Humanities.

The ‘Black Patti’

As the title of her recent biography reflects, Jones is often remembered as “the greatest singer of her race.” The opera singer, who lived from 1868 to 1933 and was referred to by her stage name, the “Black Patti,” after famous opera singer Adelina Patti, was the Aretha Franklin of her day, Rickman said. When she was home from touring, she was the most famous member of the Providence community, he said, adding that people always walked by her house slowly in the hopes of seeing her.

During her career, Jones sang for former Presidents Benjamin Harrison, Grover Cleveland, William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt, as well as for European royalty. Rickman said that because Jones was black in a time of legalized racial segregation, her appearance for such prominent audiences was “not small stuff.” What was remarkable was “not that the Kaiser of Germany was going to her concert. It’s Sissieretta going to the Kaiser’s palace,” he said.

But Jones’ performances sparked controversy. “This (was) the Jim Crow era,” Rickman said, but “her talent (was) so extraordinary, they had to make exceptions.”

For three of her four presidential performances, Jones had to enter the White House through the back door. For her Roosevelt performance, she was allowed to come in through the main door.

“I can’t quite emphasize how big this is,” Rickman said about Jones singing at the White House.

She was “someone who stepped out of lines prescribed for women of color, people of color,” said Aiyah Josiah-Faeduwor ’13, who works as a junior consultant for the Rickman Group, a Providence consulting firm of which Rickman is president. Josiah-Faeduwor began working with Rickman earlier this semester after hearing about the position at a meeting for the Brotherhood, a black male student group. He helps plan projects for the Rickman Group and is involved with the event honoring Jones.

Josiah-Faeduwor said when Rickman first mentioned Jones to him, he had never heard of the singer.

“I went and searched her and I didn’t understand how I didn’t know,” he said.

Celebrating a star

Despite her success at the time, Jones died in poverty without even the money to pay for a gravestone, Rickman said. “Fame is fleeting,” he said. “You have to be Lincoln to be known for the ages.” He said the best way to avoid forgetting someone is repetition of his or her memory, which is what Rickman hopes to accomplish with the upcoming event.

Rickman and Dimmick said the impetus for the event was a biography written by Rhode Island native Maureen Lee. Before the 2012 publication of her book — “Sissieretta Jones: ‘The Greatest Singer of Her Race,’ 1868-1933” — only one other book about Jones had been published, and it was not as comprehensive, Rickman said. Lee’s new biography provided the inspiration to hold the Black Heritage Society’s upcoming event and to “do it in a very public way,” Dimmick added.

The first part of the event will take place at the Old Brick School House on Meeting Street, where Lee will discuss Jones’ life and career. The next day, vocalist Cheryl Albright will sing from Jones’ repertoire in the Congdon Street Baptist Church to accompaniment by pianist Rod Luther. Dimmick said Albright will dress in Edwardian-style clothing, as the concert’s goal is to “create a moment in time and space where one could believe it is Sissieretta Jones come back to life.”

The event’s locations are meaningful, Rickman and Dimmick said. The Old Brick School House was Jones’ childhood school, and Jones regularly attended and performed at the Congdon Street Baptist Church. The church also provided refuge for Brown students in 1968 following their protest against the University’s insufficient efforts to recruit more minority students, according to the church’s website.

Because she was an active member at both of the event’s locations, it’s “just perfect,” Rickman said.

Rickman said he thinks the community needs more heroes like Jones, who made an impact on her community amid racial tensions. “You need to know from where you came so you can better navigate where you’re going,” Rickman said.

In times of change, Josiah-Faeduwor said, it is crucial to preserve the city’s past by remembering people like Jones. “It’s an opportunity to save what’s important,” he said.

A mark of remembrance

The event took months of planning. Dimmick said they needed to find a woman to represent Jones, appropriate venues for the event and public support. Rickman added that they conducted thorough research throughout the planning process, crediting Lee as the project’s main scholar.

His goals for the event include educating more people about figures like Jones and honoring what Jones did for Rhode Island and the world, he said.

Rickman aims to raise $2,500 at the two-part event and plans to write to singers like Aretha Franklin and Diana Ross, who he said are “standing on (Jones’) shoulders,” to ask them to match the amount of money raised. Franklin and Ross “know what it was like in a segregated society,” Rickman said.

One way to honor Jones is to purchase a tombstone for her burial location at Grace Church Cemetery in Providence, Dimmick said. Right now, “it is essentially an unmarked grave,” Dimmick said.

In June 2012, the Rhode Island Historical Society inserted a commemorative plaque for Jones at the corner of Meeting and Congdon streets. Rickman said he worked with the city to place the plaque at an angle so people walking on Benefit Street would notice it.

It’s a “perfect placement,” he said, adding that he sees tourists looking at it and saying, “‘Wow, wow, she’s important.’”

Sissieretta and Brown

Dimmick said Jones’ story has a strong connection to Brown. During Jones’ career, black female students were not allowed to live on the Pembroke campus, so they lived with residents on the same street as Jones, Rickman said. “She would have known all of them,” he said.

Rickman said he hopes current Brown students will learn about the presence Jones once had and that students will attend more community events in general.

He has been disappointed by the low number of students who attend local events, such as those organized through the Black Heritage Society, he said.

Rickman said he hopes above all that the event will raise awareness about Jones’ achievements.

“It is almost disgraceful to take this long to get her a grave marker,” he said. “The acclaimed need to be acclaimed and remembered.”

ADVERTISEMENT