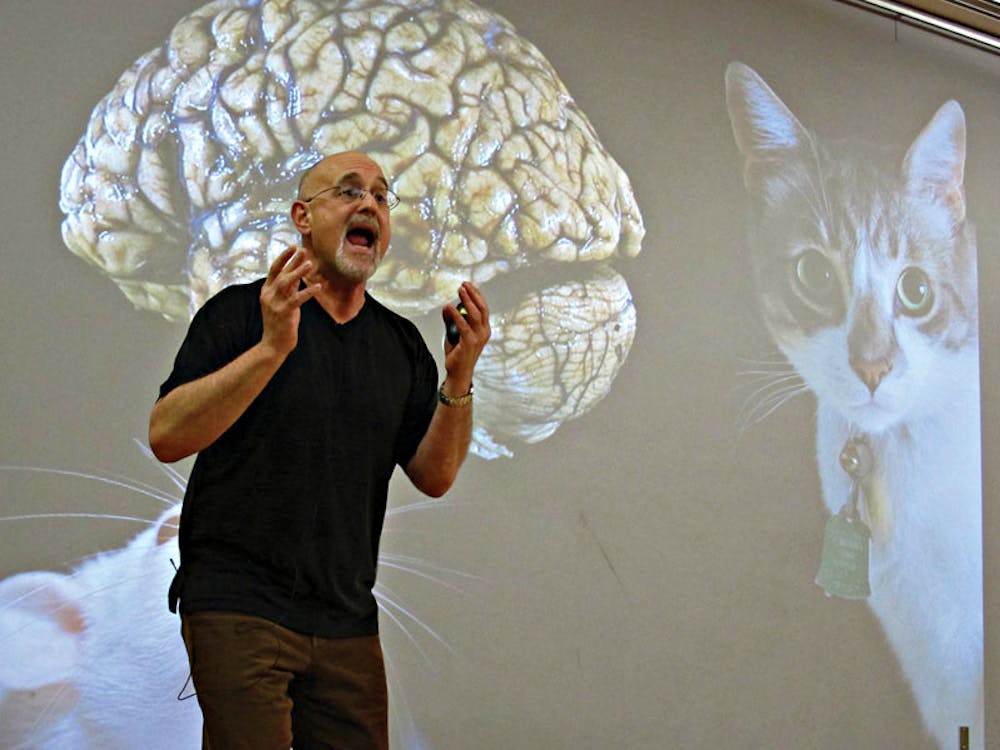

Imagination is a “life-simulator” that often poorly predicts what will bring us happiness, said Daniel Gilbert, professor of psychology at Harvard and New York Times bestselling author, in a lecture Thursday afternoon.

The talk marked the launch of the program for Ethical Inquiry, said Bernard Reginster, acting director of the program and professor of philosophy, who introduced the lecture. The program represents an effort to explore “happy or meaningful” life and will continue to host lectures throughout the spring, Reginster said.

The conception of happiness as elusive is modern, Gilbert said.

“For the first time in the history of our species, large populations of people on our planet have everything they want or could reasonably want,” Gilbert said. “And guess what? They’re still not happy.” It must then be true that the things we have decided to aim for do not make us happy, he added.

Our imagination allows us to learn from experiences we have not actually had. “So nature has given you this ability to pretend — to simulate in your imagination a variety of futures and figure out which one is the good one, which one is the bad one,” he said.

But our imagination is flawed, Gilbert said. When people are asked to predict their future happiness in a variety of situations, they often get it wrong.

He identified four principal reasons why we are poor predictors of our future happiness.

Imagination has “tunnel vision,” he said. It paints a general sketch of our future but does not include all the details. Though these small details may seem trivial, there are so many of them that they make a major difference in our experiences, he said.

Gilbert described one study that asked both Californians and non-Californians how much happier they think people who live in California are compared to people who live elsewhere. The study showed that both groups thought that Californians were happier, but the actual difference in happiness was nonexistent. The reason they all misjudged their happiness, Gilbert said, is because they imagined California as beaches and surfing, ignoring the fact that the details of their daily lives — work, commuting in traffic, marriage — would be the same.

People cannot envision a world outside of the present, Gilbert said. He cited one recent study that surveyed 18-year-olds on how much they thought they would change in the next 10 years and asked 28-year-olds how much they had changed in the previous 10 years. The study found that 28-year-olds said they had changed much more than 18-year-olds predicted they would. This poor predictive ability transcends age, Gilbert said.

We also underestimate our ability to overcome misfortune, Gilbert said.

People respond to trauma in four different ways, he said. Twenty percent are devastated for an extended period of time, 5 percent are initially fine but then see their happiness decrease over time and 25 percent are unhappy at first and then recover. But by far the largest group of people, Gilbert said, is the 50 percent who are resilient and do not experience a considerable decline in happiness.

We tend to see the world in a way that allows us to feel better, Gilbert said. Depending on the circumstances, one can call this either rationalization or coping skills, but either way, “your brain exploits ambiguity” to make you happier, he said.

Another reason why people misjudge what will make them happy is that the advice they receive is often misguided, Gilbert said. For example, our parents often advise us that marriage, money and children will make us happy.

While marriage and money increase our happiness, children actually detract from it, Gilbert said. One study showed happiness peaks at the first child’s birth and then declines severely. Another study found that being with their children brought women slightly less happiness than shopping for groceries did. “The only symptom of empty-nest syndrome is nonstop smiling,” he said.

Gilbert compared having children to bragging about cashmere socks — we tell everyone they bring us happiness because they cost a lot of money, he said. He also compared rearing them to using heroin, noting that they can “crowd out” other sources of happiness in life. Raising kids is like watching a no-hitter in baseball, he added — largely boring except for a few great moments.

But, Gilbert added, “maybe the fact that we have and love children even though they don’t always make us happy is the most noble, wonderful thing about us.”

ADVERTISEMENT