President Obama’s recent executive orders on gun violence in America will increase gun-related research on the University campus — a field that has been stifled since a 1996 statute barred federal agencies such as the Center for Disease Control and the National Institutes of Health from funding gun-related research, University researchers said.

Several University professors have spoken out in favor of Obama’s initiative to remove past barriers to gun-related research and signed a Jan. 10 letter addressed to Vice President Joe Biden by the University of Chicago Crime Lab calling to expand research on gun violence.

While the University’s gun-related research has been stymied by funding barriers and limited access to firearm data over the last several decades, University researchers told The Herald they were hopeful Obama’s recent order will remove barriers to research and breathe new life into the field.

Signature of support

Less than a month after the school shooting in Newtown, Conn., several University professors signed the letter to Biden.

In its letter, the Crime Lab recommended the federal government invest directly in gun violence research and remove “current barriers to firearm-related research,” such as limitations on accessing federal data about gun ownership, according to the letter.

Though gun research is not in his area of expertise, “it just seems reasonable that research should be treated equally to other important issues,” said Nathaniel Baum-Snow, associate professor of economics and urban studies. “I don’t think that research should be limited by statute.”

Though the topic of gun research has yet to come up in Baum-Snow’s lectures, he said it is a likely source of discussion in upcoming meetings for his class ECON 1410: “Urban Economics.”

Gun research is important because it provides evidence-based recommendations for public policy, said Megan Ranney, assistant professor in the department of emergency medicine.

“Creating policy based on emotion is often the way laws get created,” she said. “But without science and evidence behind it, we often see laws don’t have the intended effect.”

The lobbying effect

The force behind the federal restrictions is the National Rifle Association, Ranney said. A powerful interest group, the NRA encouraged a group of Republican senators to pass the gun research ban in 1996, she added.

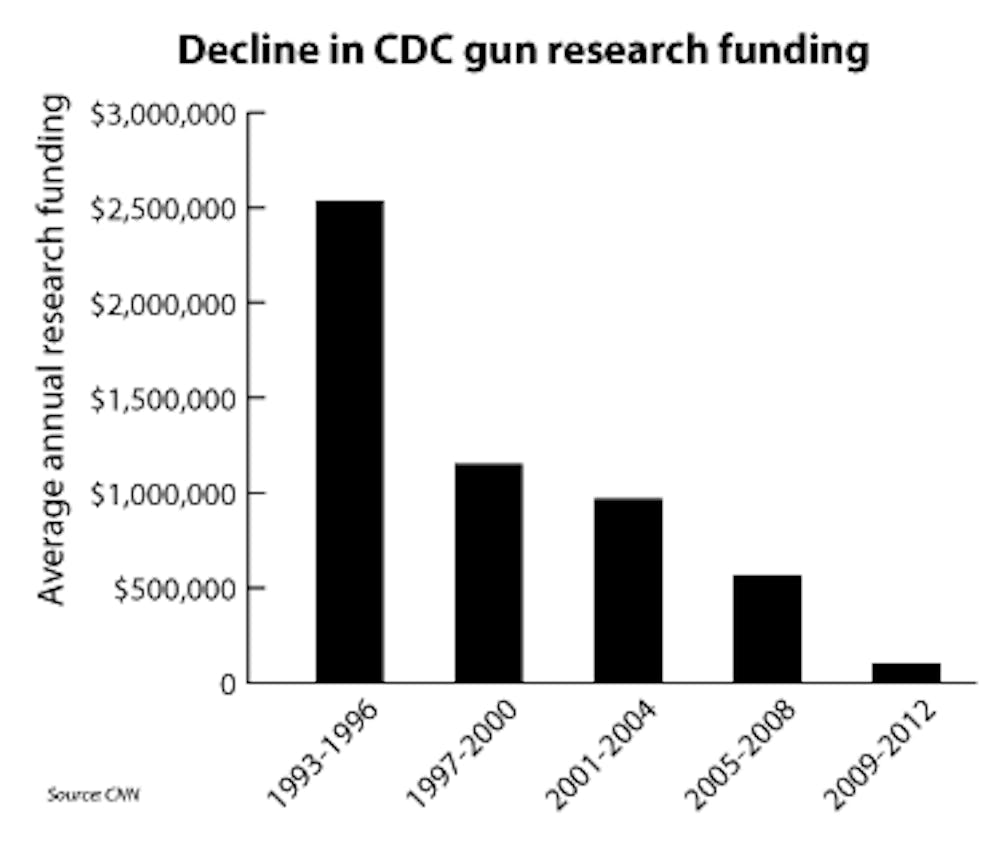

Since the ban’s passage, “the number of public health researchers (looking into gun-related issues) has decreased pretty precipitously,” Ranney said. “Most of the good articles you find are from the 1990s.”

Ranney said claims that gun-related research is too political were misled.

“The whole idea of research as political is baloney,” she said. “Research is research — it’s done scientifically.”

Barriers to funding

On campus, there is “no coordinated effort on gun-related research,” said Brian Knight, professor of economics. “It’s more individuals pursuing their own research agenda.” The lack of federal funding “certainly hampers research in the area,” he added.

Knight’s own interest in gun research was sparked when he heard anecdotal evidence of a gun trafficking network between states with strict gun laws and states with loose laws, he said.

Analyzing data about where guns were purchased versus where they were later found, Knight discovered that a significant fraction of American firearms — approximately one-third — were purchased in a different state from where they were found, he said.

Tracing data — information that allows researchers to “trace” where a gun was purchased — used to be widely accessible to researchers, Knight said. But in 2003, the federal government heavily restricted access to this data, he said. As a result, Knight was forced to examine aggregate data by state, rather than tracing data on individual firearms, to conduct his study.

“We tend to see a lot of flow from states with weak laws to states with strong laws,” Knight said. “What this means is that states don’t have complete control over their gun policy.”

This results in a “lowest common denominator” effect, whereby states with the least strict laws set a standard for gun acquisition that ultimately affects many more states as firearms are transported across state lines, Knight said. This is the cost of “a patchwork of policies” rather than a stronger federal law infrastructure that dictates gun laws across states.

Knight did not receive federal funding for his research, and he said doing so “isn’t easy for anyone” when it comes to studying guns.

The lack of federal funding affects other fields of study that would otherwise engage with gun-related research. “Public health and physician researchers are less likely to do research on firearms because there is not money for it from the NIH and CDC,” Ranney said.

“It’s really difficult to do good research on firearms if you are not getting funding from any sort of national organization, “ Ranney said, adding that there have been a number of researchers at the Injury Prevention Center who have been blackmailed for pursuing gun-related research.

To skirt the federal government’s restrictions on gun-related research, Ranney said researchers pursue gun research discreetly.

Ranney is currently researching on violence among adolescents and has received federal funding to examine ways to prevent teenage girls from getting into fights. In applying for funding, Ranney did not mention firearms, but when surveying her subjects, she included several questions about whether they have been put in front of a gun, she said.

Data problems

Limited access to data has affected the research efforts of Emilio Depetris-Chauvin GS, who recently authored a study currently under review for publication that analyzes the effect gun demand had on Obama’s election in 2008.

The study found an increased demand for guns in 2008 — a phenomenon Depetris Chauvin dubbed the “Obama effect” — that was correlated with a fear of future Obama gun-control policy and racial prejudice, according to the study.

To conduct his research, Depetris-Chauvin had to rely on national background check reports. The 1994 Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act requires gun purchasers at federal license stores to undergo a background check. While these data are helpful, gun purchases at gun shows are not included, he said. “You only have gun ownership data on the state level every ten years — that’s a problem,” he added.

Working with what he could — most notably data that told him how many monthy background checks were run in each state — Depetris-Chauvin tracked data beginning in March 2007. Because there was no reliable agency tracking the number of guns or gun owners, Depetris-Chauvin said he called every police department he could and got data directly from them.

The available data come at a price — Depetris-Chauvin said Chicago’s city survey, which included questions about firearms, would have cost him $1,000 to purchase.

What he found was a “huge surge” of gun purchases in November, especially the week before the election. Compared to the year before, there was an 80 percent increase in purchases, he said. There was also a “huge peak” in some particular states in July of 2008, when “people started to get information about Obama winning the election,” Depetris-Chauvin said.

Obama’s order

Expanding gun research and the new laws Obama has proposed to curb gun violence have met controversy due to criticisms that gun research is inherently political.

“Only honest, law-abiding gun owners will be affected, and our children will remain vulnerable to the inevitability of more tragedy,” the National Rifle Association said in a statement. Critics of Obama’s plan have expressed skepticism the new laws would result only in a drainage of the nation’s budget and a hassle for the average gun-owner, rather than a stop to mass shootings.

But without trying, researchers cannot know if their work will curb gun violence, Baum-Snow said.

Knight said gun violence research is important in the current sociopolitical climate because the United States is an “exceptional case” when it comes to gun policy. The United States has weaker gun laws and higher gun ownership rates than comparable nations and much higher gun violence and homicide rates, Knight said.

Obama’s executive order to appropriate money for gun-related research is now in the holding pen until Congress appropriates money for the fund, Ranney said.

“If Congress provides money for research into firearms, there will absolutely be an increase in research,” she said. The timeline “really depends on Congress and how quickly they move.”

Michael Mello, associate professor of emergency medicine and associate professor of health services, policy and practice, said he thinks reforms in research will decrease gun violence. “There is no one clear solution to a complex problem,” he said. In the same way multiple levels of intervention were necessary to decrease motor vehicle crashes by 31 percent, the issue of gun violence must also involve “multiple interventions,” Mello said.

Ranney predicted that as soon as the federal ban is released, researchers will launch projects examining gun-related issues. The first projects would be “small-scale research,” while larger projects would take more time to receive funding due to the extensive application process, Ranney said.

“People aren’t going to be afraid anymore that it is going to blackmail their research career,” she said.

An previous version of this article incorrectly stated that the research of Emilio Depetris-Chauvin GS studied the effect gun demand had on Obama’s election in 2008. In fact Depetris-Chauvin analyzed the effect of the likelihood of Obama winning the election on the demand for guns. The article also stated that Depetris-Chauvin thought about purchasing Chicago city’s survey, for $1,000, when in fact it was the GSS survey from NORC at University of Chicago, which was approximately $800. The Herald regrets the errors.

ADVERTISEMENT