In 1986, Students Against Testing submitted a referendum to the Undergraduate Council of Students urging the University to stop requiring applicants to submit SAT scores. Mark Safire ’87, co-founder of Students Against Testing, raised issues that still echo among applicants and students today.

“It’s not an aptitude or achievement test. I’d like to know exactly what it’s supposed to measure,” Safire said, The Herald reported at the time.

Safire’s movement did not succeed in 1986, but today, many schools have embraced the argument of Students Against Testing. Approximately 850 four-year colleges have become standardized test-optional in their admission processes, according to Bob Schaeffer, public education director for the National Center for Fair and Open Testing. These schools have instituted a new policy in which applicants are not required to submit SAT or ACT test scores in order to be admitted.

But none of the Ivy League universities are test-optional, as all eight still require some combination of the SAT I, SAT II subject tests or the ACT with or without the writing component. Brown requires applicants to submit either the SAT I with two subject tests or the ACT with the writing component.

“Test-optional is defined as not requiring SAT or ACT test scores to be submitted before admission decisions are made for all or many applicants,” Schaeffer said.

The shift to a test-optional policy among many schools comes from an increasing belief in universities and colleges that standardized test scores are an inadequate predictor of a student’s success at the college level.

“There is research data that suggests the test adds little or nothing to select and predict who will be good students,” Schaeffer said. “Every school that goes test-optional sees an increase in academic talent of its applicants.”

“The SAT predicts first-year grades not quite as well as high school grades do — despite differences in high schools,” Schaeffer said.

For the first time, the number of students taking the ACT surpassed the number of students taking the SAT. According to data from ACT and College Board, 1,666,017 students took the ACT in 2012, compared to 1,664,479 students taking the SAT.

Rob Franek, author of the Princeton Review’s “The Best 377 Colleges,” attributed the rising interest in the ACT compared to the SAT to students’ desire to submit scores from the test they find more conducive to their own abilities.

Schaeffer noted that some colleges that have moved against mandatory standardized test submissions still require students to submit their GPA or class rank, such as the University of Texas, which automatically admits students in the top 8 percent of their graduating class.

Dean of Admission Jim Miller ’73 said the use of standardized test scores varies by each institution’s individual needs.

“While we get transcripts — which are the most critical things we get — and teacher recommendations and essays, one of the things standardized tests does is help give us a sense of comparing apples to apples,” Miller said. “It’s nowhere near the most important tool, but it does add to our understanding of a student’s credentials.”

Current students and applicants gave mixed responses as to whether they found standardized test scores to be useful in the admission process.

Mary McCreary, an applicant to the class of 2017 from John Paul II High School in Plano, Texas, said she supported the Admission Office’s use of the SAT because she felt her high score on the test helped her compensate for her lower GPA.

Ashrat Patel, who attends Chapel Hill High School in Atlanta, Ga., said standardized test scores “don’t measure intelligence or how you do at a university.”

Patel said he chose to take the ACT instead of the SAT because he felt he could better understand the test’s format and material. He said the SAT “takes a sort of mindset, which varies for each student.”

Some students and applicants indicated they feel these tests merely measure students’ abilities to do well on the tests themselves.

“Something about how the questions were set up showed me it wasn’t testing what you learned in high school,” said William Van Ullen, an applicant from Christian Brothers Academy in Albany, N.Y. “I felt all of the questions were trying to trick you.”

Franek said he believed standardized tests are not predictors of a student’s success. “The SAT is an incredibly coachable test and no way predictive of a student’s aptitude,” he said. “The SAT ... only stands for the three letters.”

But Franek said many admission offices still see standardized tests as useful. He added that 82 percent of 1,500 four-year colleges that have reported how they use various criteria indicated test scores were “very important or important” in their admission decisions, according to a recent Princeton Review survey.

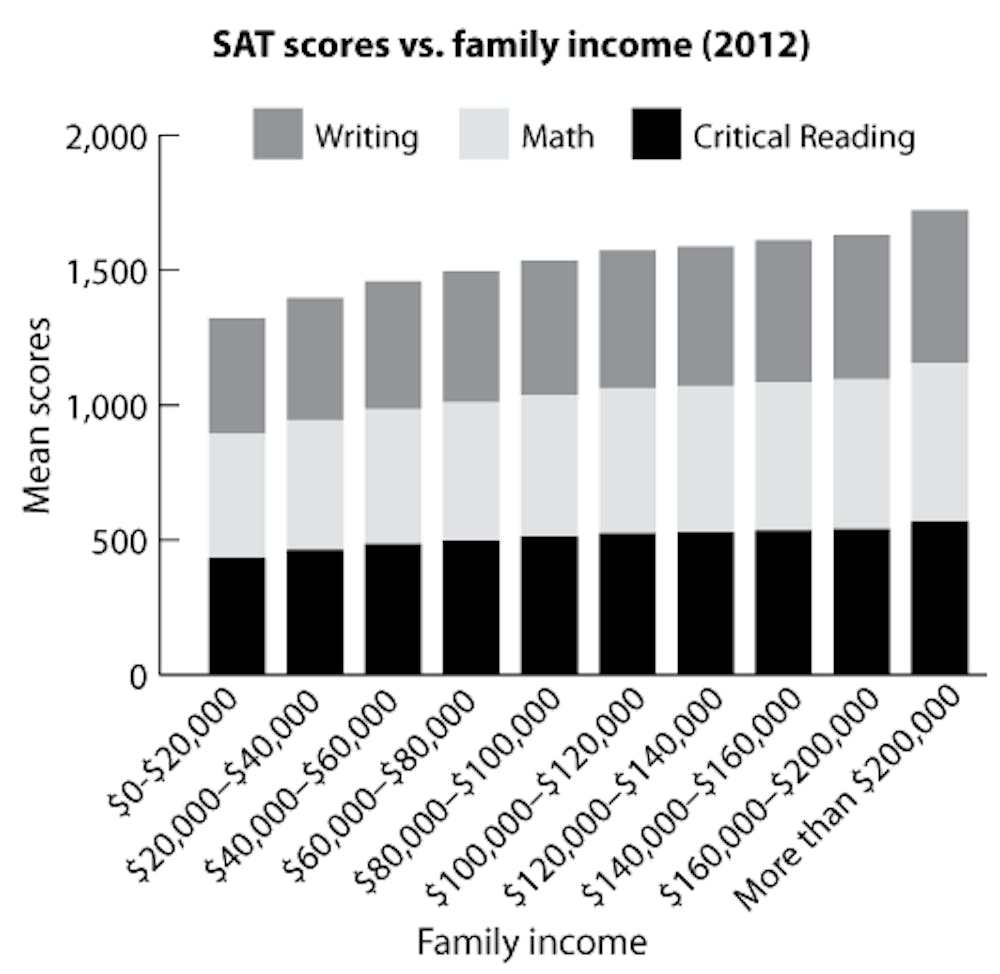

Socioeconomic differences are another thorny part of the debate over the value of standardized tests. According to statistics by the College Board, as a student’s family income increases, a student’s SAT scores increase.

“Students who pay for courses to get higher scores are being resourceful,” Patel said.

Franek noted there are many options for test preparation that vary in price, making preparation affordable for everyone.“It just depends on what is the best platform that you learn on — from a book or a one-on-one tutor,” Franek said.

Samuel Kortchmar ’16 participated in a Princeton Review camp to prepare for the SAT. He said he liked the SAT because it gave him a way to measure himself against a national standard. “It strengthened my application,” he said. But he said he found the writing section to be an area where tutoring classes could make a large difference in improving students’ scores.

“My writing hadn’t improved,” Kortchmar said, adding he felt the tutoring course only gave him an edge in learning the test’s format.

Some students indicated they felt their high schools left them at a disadvantage in performing on the SAT and ACT.

Conor Wuertz ’16 said he came from an “experimental high school” that put less emphasis on exams and left many students unready for standardized tests.

“Standardized tests don’t test creativity or the ability to work together with others,” he said. “It’s not a good indicator of college success.”

Weurtz said he would like admission offices to either use a modified standardized test or other criteria that measure skills besides test-taking abilities.

Some students said standardized test scores seem to only have relevance for the admission process but have little impact on life after college.

Xander Tabloff ’12, who now attends Yale Law School, said the SAT “certainly wasn’t a huge predictor of where (students) went or what jobs they got after Brown.”

Director of the Center for Careers and Life After Brown Andrew Simmons wrote in an email to The Herald that he is aware some employers request standardized test scores in the job application process. He added that banking and consulting firms are the primary users of test score data when hiring employees.

“The practice is not widespread, and the reasons for it are unclear,” he wrote. But “the vast majority of employers ... do not require standardized test scores.”

ADVERTISEMENT