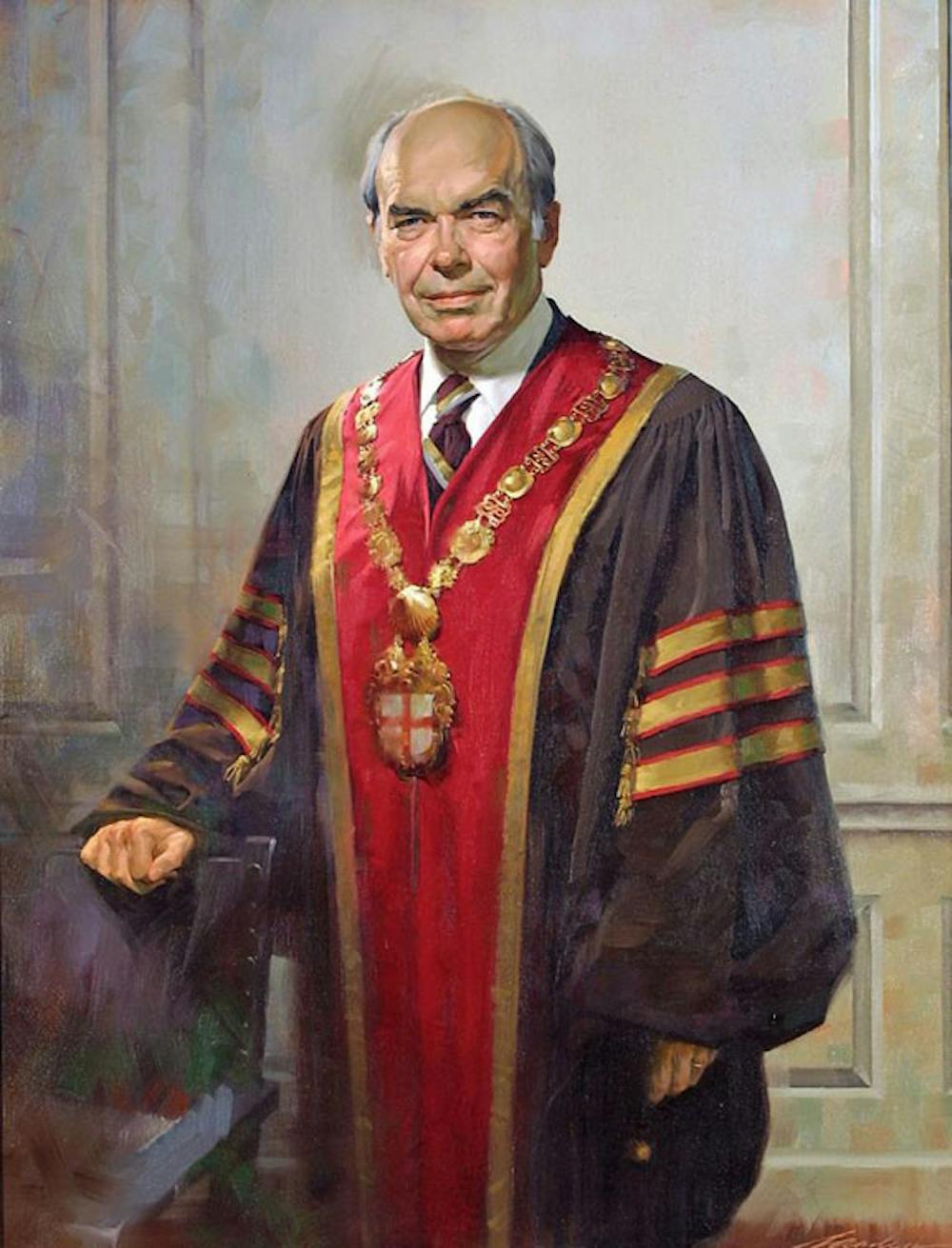

Donald Hornig, the University’s 14th president, died Monday at the age of 92, according to a University press release.

Hornig served as president from 1970 to 1976.

Like his predecessor, Ray Heffner, Hornig presided over the University during tumultuous times. During his tenure, he faced campus-wide debate over the New Curriculum, which was established in 1969, and tension over the merger of Brown and Pembroke College — the University’s women’s college — in 1971, The Herald reported at the time.

Under Hornig’s leadership, controversy over the recruitment of black students and faculty members also arose, The Herald previously reported.

During Heffner and Hornig’s presidencies, “we always had a crisis every week,” Thomas Banchoff, a professor of mathematics who has been at the University since 1967, previously told The Herald.

Hornig also oversaw the development of the University’s degree-granting medical program, according to Encyclopedia Brunoniana.

An academic leader

Hornig first came to the University in 1946 as an assistant professor of chemistry, and five years later, at age 31, he became one of the youngest faculty members at the time to be promoted to full professor. He served as associate dean of the graduate school from 1951 to 1952 and became its acting dean the following year, according to the Office of the President’s website.

After receiving his Ph.D. in chemistry from Harvard in 1943, Hornig became a group leader at the Los Alamos Laboratory, helping to create the first atomic bomb, according to Encyclopedia Brunoniana.

In 1957, Hornig left Brown for Princeton, where he became chair of the chemistry department. Before returning to Brown as University president, Hornig became a member of the National Academy of Sciences and served as a scientific advisor to Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon, according to Encyclopedia Brunoniana.

Thomas Paine ’42, who served as the head of NASA from 1969 to 1970, previously told The Herald that when Hornig served as a presidential advisor, he was “a vigorous champion of the universities as a major national strength and of sound, vigorous government-university relations.”

In 1970, The Herald noted that Hornig had published more than 80 scientific papers.

His selection as president of the University marked the first time students and faculty members participated in choosing the University’s leader, The Herald reported in 1970.

In a Herald editorial published the day after Hornig’s selection was announced, Hornig was hailed as a “dynamic, forceful leader for the University.” He was also described as “candid and honest.”

Financial strain

Despite initial student optimism about his selection, Hornig’s popularity faded when he proposed steep budget cuts to improve Brown’s financial stability, according to Encyclopedia Brunoniana.

In 1975, Hornig told students, “We have been acting educationally as if our endowment were $100 million greater than it really is,” The Herald previously reported. If the University continued to spend at the rate it had been spending, he told them, its capital endowment would run out within five years.

Hornig told students that $1.8 million would be cut from student services the following year and that financial aid would be cut by $60,000, despite student concern about its potential adverse effects on minority student recruitment. His plan also included a reduction in the size of the faculty.

Hornig was unreceptive to student input when making budget decisions, The Herald reported in 1975. “I don’t think students are financial experts,” he said at the time. He added that students generally do not think about the long-term interests of the University.

In response to Hornig’s announcement of budget cuts, students formed a group called the “Coalition” to protest his plan. Their demands included a need-blind admissions policy and a reduction in the number of cutbacks to student services, according to 1975 Herald archives.

Around 2,500 students staged a four-hour rally on the Main Green in support of the Coalition’s demands, prompting Brown’s Advisory and Executive Committee to form a student budget committee, The Herald reported at the time.

Still, the administration denied students’ requests for access to all of the information concerning the University’s budget, according to Encyclopedia Brunoniana. When administrators failed to meet the Coalition’s list of final demands in April 1975, over 3,000 students voted to stage a four-day strike.

Two weeks later, nearly 40 minority students occupied University Hall for nearly two full days.

Ultimately, the administration refused to meet any of the Coalition’s demands. Hornig stressed the importance of bringing the University onto solid financial footing but also promised to recruit and support more qualified minority students.

The following July, Hornig announced his resignation. “I would not call it a satisfying experience,” he said of his time as president. “It was bittersweet.”

Still, Hornig met his goal of improving the University’s finances. When he resigned, he had reduced the annual deficit from $4.1 million to $636,000, according to a University press release.

President Christina Paxson called Hornig an “exceptional scientist” in the press release, adding that “he was able to make difficult fiscal decisions that put the University on a firm footing. … Much of Brown University’s success over the last three decades had roots in these decisions, for which we remain grateful.”

ADVERTISEMENT