Stand-up comedian, writer, actress and this spring’s Brown Lecture Board speaker Ali Wong was first asked, in her May 13 virtual lecture, about her Zoom life and if she was wearing pants. In response, she flashed her high-waisted slacks to the camera.

“I'm wearing pants, I'm wearing this — they’re sweatpants. But you know real high-waisted, or Steve Urkel vibes. For those of you who are almost 40,” Wong said.

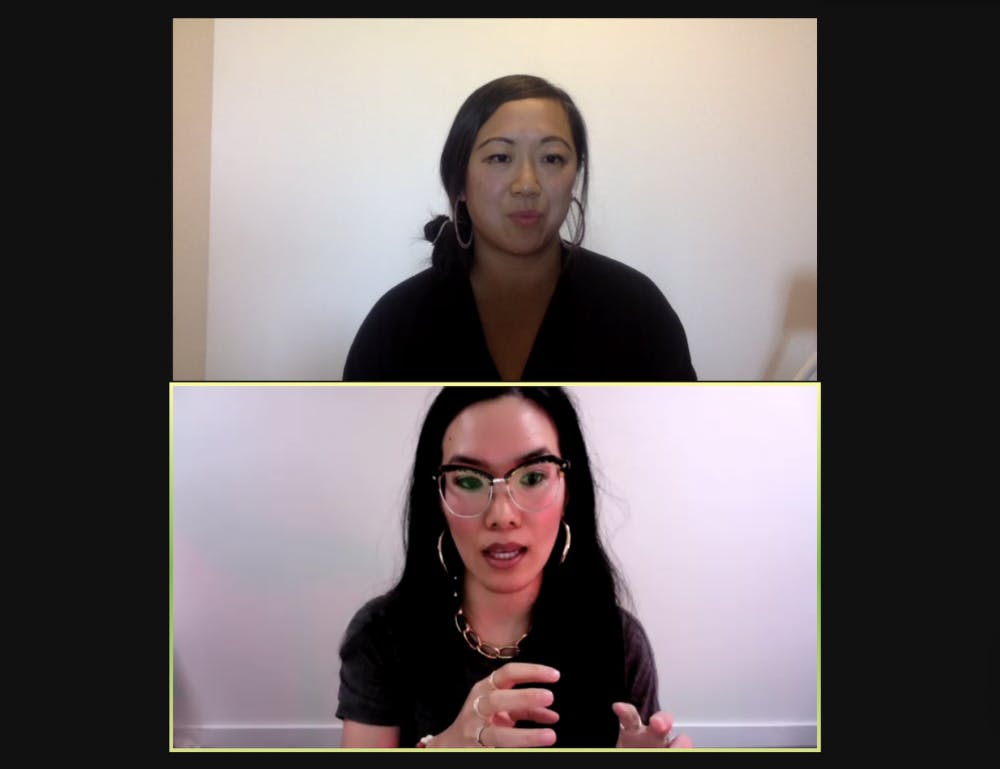

The pants question kicked off a conversation between Wong and Elena Shih, assistant professor of American Studies, the event’s moderator. The Q&A explored failure, motherhood, comedy, Asian American identity and Wong’s creative process on Thursday evening.

Megan Yeager ’22, president of BLB, said that the organization sought to represent the interests of the student body and broader community when deciding on the spring semester’s speaker.

“We were thinking about the general hate that Asian American people have experienced, and we really wanted to uplift Asian voices in our programming,” Yeager said. The BLB also wanted a comedian to keep things light and humorous, and Ali Wong more than fit the bill,” she said.

Wong wears a variety of hats and has worked on several projects with Netflix. Through the platform, she hosted two acclaimed stand-up specials, clad in her signature animal print and boasting a baby bump. Wong also co-stars in the animated show “Tuca & Bertie” and co-wrote, executive produced and starred in “Always Be My Maybe,” an Asian American rom-com with Randall Park.

She also recently authored the book “Dear Girls,” a humorous and advice-driven tell-all addressed to her two daughters. Wong said that the writing process for her book was more challenging than writing her comedy without the real-time feedback that comedy shows offer.

While showing Shih her at-home work environment, Wong produced a black box that she uses to record voice-overs for “Tuca & Bertie.” The second season of the show is slated to premiere on Adult Swim this June.

“I stick my head in there in my closet, and I pretend to be a bird opposite Tiffany Haddish, who also plays a bird,” Wong said after putting her head in the box as a demonstration.

When asked about the inspiration behind her 2019 movie “Always Be My Maybe,” Wong said she and longtime friend Randall Park had always talked about making an Asian American version of the classic American rom-com “When Harry Met Sally.” The two participated in the same comedy troupe while attending the University of California, Los Angeles, and they kept in touch throughout their later careers.

Looping Keanu Reeves into the film was another story. Wong said she wanted all of the main character’s love interests to be Asian men, and needed someone who could one-up the second love interest, Daniel Dae Kim — whose “face has abs.”

“He's got to be iconic because Daniel Dae Kim is already so iconic,” she said. “He has to be funny and willing to make fun of himself.”

For Wong, Reeves fit the profile perfectly. Wong walked the audience through the story of reaching out to Reeves, who was a fan of Wong’s first comedy special “Baby Cobra.” The two went on to meet with the director of the movie, and Reeves’ enthusiasm for the part was immediately apparent. In their first meeting, Reeves began to assume the role, practicing the air punches and kicks that his character does in the movie.

“We sent him an updated draft of the script, and he wrote me back saying, ‘You know, it would be an honor to be part of your love story,’” Wong said.

Speaking to her interest in comedy, Wong explained that as the youngest of four children, it was validating to make people laugh, though she never truly considered it a viable career path because of the lack of Asian representation in the field.

“Any effort I made towards a career in comedy all came from really pure passion and desire,” Wong said.

Doing stand-up after graduating from UCLA with a degree in Asian American Studies helped Wong get back into comedy after college. Her first open mic was at a “half-cafe, half-laundromat, one hundred percent homeless shelter” in her hometown of San Francisco, she said.

“I loved it so much and then after that night, I think I was determined to go do an open mic every single night,” Wong said. “It's been my practice ever since that day to do as low as three sets to as high as 29 sets a week,” excluding special circumstances like her honeymoon, the births of her two daughters and the COVID-19 pandemic.

“People always think that (comedy is) about making people laugh, and it is, but it's a lot about surprise,” she added. “If you hear something that is predictable and unoriginal you're not gonna laugh.”

A big theme of the night was failure, which Wong said was inherent to comedy. Her rise to the top, she explained, began when she had to wait a year to book seven minutes on stage at the Punch Line San Francisco comedy club. When the moment finally came, she “bombed so badly that nobody would even speak to me right afterwards, they all treated me like I had just farted,” Wong said.

All the more determined, Wong got her second chance six months later, and had “a really good set.” Half a year after that, she was asked to host an event back at the Punch Line called the Sunday Special, and by the time a full year had passed she was hosting for the big headliners at the club.

Failure in comedy is a form of learning through reiteration, Wong said. Oftentimes, the final product of Wong’s jokes is born out of failed iterations from an original idea.

For a joke about Sheryl Sandberg’s book “Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead,” Wong uses the famous line: “I don’t want to lean in, I want to lie down.” Even for this short punchline, Wong had to navigate the best phrasing and word choice to elicit laughs from the audience.

“I could have also said, ‘I don't want to lean in, I want to relax. I don't want to lean in, I want to sleep’… that process of failure and bombing really helped me arrive there,” Wong said.

“It’s exciting to see her success, see her being Asian and simultaneously loud, raunchy, funny,” said Abby Chun ’22, who attended the lecture. “It’s exciting to see her celebrated for being the things you’re usually not supposed to be as an Asian woman.”

Chun said the way Wong talked about failure was encouraging. “Her outlook on failure and the way that she framed it as a moment for growth and used it as an opportunity to improve her writing and workshop stood out to me.”

On motherhood, Wong talked about having to reorient when a complication in her pregnancy meant she had to be induced at 37 weeks. Losing her idealized plans for a “hippie wavy davy” natural birth taught her the lesson of letting go, she said.

When asked about her response to violence toward Asian people, Wong said the subject is “always on my mind… I'm always really affected by it.” Wong added that she has respect for and directs resources to organizations and activists.

As to the power of representation in the media, “Anybody who's Asian American doing anything, I get excited about,” Wong said. She emphasized the importance of having Asian Americans not only on-screen, but also behind the camera, including in director and writer positions.

Shih said she was very excited that BLB chose to bring Ali Wong since she is “the first woman speaker in a few years, Asian American (and) a mother working in an industry that has been impacted by the pandemic.”

“I really think she was a great speaker for this moment because of her ability to spin things that are pretty devastating and personal, and make them hilariously relatable,” Shih said.

This year’s two virtual BLB speaker events have been hosted by professors instead of students, given that professors tend to have more virtual moderating experience, Yeager said. Students will likely take up the mantle of hosting when events migrate back to an in-person setting, she added.

Yeager was excited about the event because “it’s rounding out a really horrible year.” She hopes it can be “a bright spot in people’s lives… something that people can laugh at and engage with.”

ADVERTISEMENT