Since our University first crowned campus with its Edifice (now University Hall), a league of extraordinary Brunonians have sought to summit its roofs, survey every nook and sneak through its tunnels. Whatever force compelled Amos Hopkins, class of 1795 to climb up to the cupola of University Hall in 1792 persists to this day — marking an almamatriotic throughline that links the spirits of intrepid students across more than two centuries. The University has long celebrated this tradition of exploration; among its participants are Brunonia’s most adoring adherents and visionary pioneers. Now, despite all that this tradition has given — from lasting institutions to a sense of belonging and significance for countless students — University Hall takes unprecedented and misguided action to sever it.

⁂

For the title of Brunonia’s Oldest Tradition, the exploration of Brown’s roofs, nooks and tunnels vies only with our tradition of student activism, preceding it by just a few years. In 1792 — the year that Brown University hoisted its bell into the cupola of the College Edifice — Amos Hopkins, class of 1795, summited its roof with a jackknife to sign his name into one of the cupola’s upright frames. Hopkins was no outlier; in 1803, Henry D’Wolfe, class of 1806, repeated the feat. By contrast, the University’s first recorded display of student activism was a 1798 protest featuring surreptitious entry: That April, tensions between students and the administration culminated with students infiltrating University Hall in the dead of night to fill the locks of the door to the bell with lead. As the bell was essential for timekeeping, the protesters significantly disrupted University business the following morning.

Despite these roots in vandalism and insurrection, Brown’s prohibition on unauthorized access was entirely passive until the spring of 1939 — Brown’s roof hatches had previously not been locked. It was in this permissive climate that students claimed Brown’s roofs and tunnels for the mundane as well as the extraordinary. Until that Spring, a Herald editorial reported, it was common for students to sunbathe on dormitory rooftops. But, The Herald continued:

Now it is a different story. Dorm roofs have been locked, barred and sealed; strict vigilance has been used to keep sunbathers from the perils and pebbles of Littlefield, Maxcy, Slater and Hope. The result: numerous complaints from tan-seekers and consequent migration to the campus.

(The Herald concluded that the ploy was futile: “Clamping down on sun-bathing is like prohibiting Pembrokers from using the John Hay. Try and do it!”)

It is to this formerly lax prohibition on unauthorized access that we owe the existence of college radio as we know it. The Brown Network — predecessor of the Brown Broadcasting Service (WBRU) and Brown Student Radio — gained a permanent foothold on campus in 1937, when Dave Borst ’40 orchestrated the stringing of 16,000 feet of transmission line between Brown’s rooftops, and the snaking of a whopping 30,000 feet of line through the steam tunnels. (This tunnel transmission network, with some modifications, remained operational as late as 1994.) In May 1940, an AM antenna mounted by students to a chimney of Slater Hall made possible the first transmission of the Brown Network beyond the confines of College Hill — a feat garnering national attention.

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="900"]

These landmark achievements of the students of the Brown Network utterly lacked University approval. In his memoir, The Gas Pipe Networks, Louis Bloch ’40 recollects how only a wave of national attention saved the nascent organization from administrative injunction:

The Dean had grievances about The Brown Network and summoned George and me to appear in his office the following week. … When we arrived at the Dean’s office for the meeting, he stated that we had no business climbing over the buildings, and stringing our lines through the heating tunnels. He then opened his desk drawer which revealed hundreds of press clippings received from almost every state describing the great contribution which Brown had made by developing a new extracurricular activity which was in step with the times. Also the press praised Brown for permitting an activity which was certain to become a most important training ground for the radio industry. The Dean’s only comment was, “So What Can I Say”.

The University now lauds these pioneers in its marketing and alumni communications. An online timeline produced by the University in celebration of its 250th anniversary proclaims “College Radio Born At Brown” beside a photograph of radio pioneer George Stuckert ’42 straddling a chimney cap of Slater Hall. This timeline, developed to celebrate the “shared ethos that values discovery, creativity and collaboration; and the persistent drive — by its community of faculty, students, staff and alumni — to build a better Brown,” neglects to mention that the administration’s stance towards the Brown Network during its formative years ranged from apathy to hostility. While Bloch’s story has a happy ending (“After that incident, the Dean became a good friend and we had no further problems,” he wrote), this column does not: In 2019, our administration took unprecedented and misguided action to subdue would-be student adventurers by targeting campus exploration in a document governing the base principles of our community.

⁂

The Brown University Student Code of Conduct has long served to outline the barest standards of behavior that we Brunonians must uphold; we shalt not engage in bribery (§D.2), nor harass others (§D.9), shalt not steal (§D.21) — to name a few. At its best, this document has encoded our most fundamental values. The 2012 edition of the Code of Conduct, for instance, begins with an exposition of students’ rights, followed by a list of just twelve offenses. With the unfortunate exception of a federally-required drug policy, these prohibited behaviors are acts that would interfere with the basic rights of students or the functions of the University. This roughly 1,200 word document unobjectionably succeeds as representation of the basic values of the Brown community.

In contrast, during the tenure of President Christina Paxson P’19, our Code of Conduct has bloated into nearly 4,000 words of legalese that outline twenty-four prohibited behaviors. It no longer begins with, or even includes, an exposition of students’ rights. Although several of the prohibitions adopted by the 2019-20 edition of the Code are outright repugnant to basic decency — I’ll tackle these in my next column — two new prohibitions merely demand that we disavow the values of curiosity and collaboration that are the ethos of our community: “Unauthorized Entry or Use of Space” (§D.22) and “Collusion” (§D.3).

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="1071"]

Such prohibitions are harmless as operational policies. At worst, their enforcement irritated the displaced rooftop sunbathers of the Herald’s editorial staff — with whom I agree “that the administration is sincere in its efforts to keep the dormitory roofs for their original purpose” in the interest of public safety. However, when Bloch and his countless collaborators surreptitiously constructed the Brown Network, the greatest academic risk they faced was an order to cease and desist from an administrator. Today, they would face immediate censure, probation, suspension and potential expulsion on the grounds of trespass and collusion on a grand scale. I question whether they would have even attempted to create their network in such circumstances. In elevating their “offenses” to the same level as theft, bribery and rape, our administration demands that we disavow the actions of student explorers as fundamentally un-Brunonian.

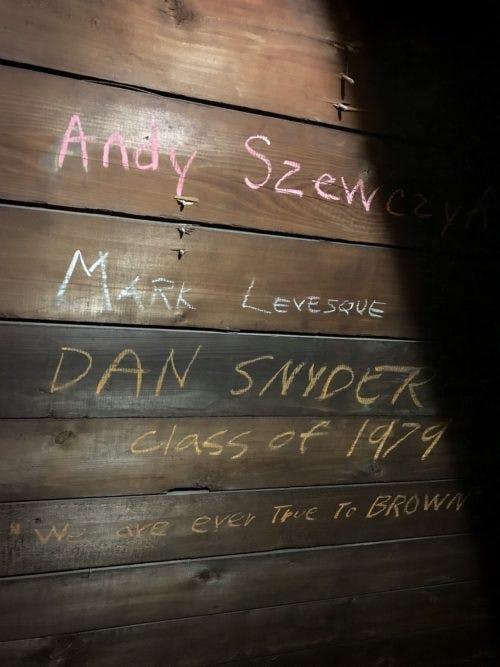

On the contrary, our explorers past and present are united by their remarkable reverence for Brown, and their feats rightfully captivate — not repulse — much of our community. The achievements of legendary “nightclimbers” Peter Blatman ’74 — famed for his ascents of the Sciences Library, the Sharpe Refectory, Sayles Gymnasium and many, many more — earned him a breathless feature in the April 1972 issue of Brown Alumni Monthly. In it, he reflects on the “spiritual kinship” he felt toward predecessors like Dennis Merritt ’67 and Cherry Austin ’67, authors of A Climbing Guide to Brown University. Likewise, Whit Schroder ’09 and Ben Struhl ’09 — subjects of a thrilling March 16, 2007 profile by The Herald — cite the thrill of discovery and the connection they felt to Brown’s past as motivation for their adventures. Dan Snyder ’79, Mark Levesque ’79 and Andy Szewczyk '79 — who chalked their names into the eves of Wilson Hall — state their ethos plainly: “We are ever true to Brown.”

⁂

Six years ago, I sobbed with joy when I got notice of my acceptance to Brown University. To come here was, simply, a dream come true. To feel as though I belonged here — a new PhD student fresh from the University of Rhode Island — was not so simple. In that perilous, isolating first year, it was through connecting with Brown’s historical and physical landscapes that I gained my sense of belonging (and countless cherished friendships). In the years since, I’ve sought to preserve the history of campus exploration, amassing a collection of Herald clippings, oral histories and an archive of more than five thousand photographs that spans decades.

I will not be the last of Brunonia’s explorers, but I might be the last to write here about it. Our administration’s sanctions will not quell students’ curiosity for their campus. Instead, it will silence and isolate them. Unfortunately, Brown’s explorers-to-be would be wise not to share their experiences with The Brown Daily Herald, Brown Alumni Magazine or any other publication, as their predecessors once did. And student publications like The Brown Daily Herald would be wise to steer clear of such stories, lest they be charged with “collusion” (i.e., “knowingly or recklessly aiding, abetting, assisting, or attempting to aid or assist another individual to commit a violation of the Code.”). Indeed, it was a Herald story that recklessly introduced Blatman to his collaborator John Lewis ’75, a Herald story that recklessly introduced me to the likes of Ben Struhl and this column that will recklessly connect you, dear reader, to campus exploration long after I graduate.

Now, I prepare to leave campus for my next, yet-unknown adventure. As I walk past the unwelcoming doors of our mostly-shuttered campus, I cannot help but reflect warmly on not only the corridors I wandered, the roofs I conquered, the tunnels I mapped and the mysteries I stumbled upon — but also the recognition that I am not the first to do so. What a thrill it is to feel kinship with a graduate of the class of 1795! Yet, equally, I despair that the administration of my soon-to-be alma mater repudiates the facet of Brunonia in which so many of us found our sense of belonging. We are ever true to Brown.

John Wrenn MS’18 PhD’21 is a fifth-year doctoral candidate. He can be reached at me@jswrenn.com. Please send responses to this opinion to letters@browndailyherald.com and op-eds to opinions@browndailyherald.com.