A public hearing for an addition to the College Hill historic district will go on as planned later this month after a failed attempt by the University to slow the process in late January.

The new zoning ordinance — and the University’s opposition to it — represents another contentious chapter in the relationship between Providence and the University that has shaped the city’s East Side.

The ordinance, which has yet to pass, would add buildings on College Hill to the historic district overlay, a zoning area with specific rules intended to preserve the architecture and character of the neighborhood.

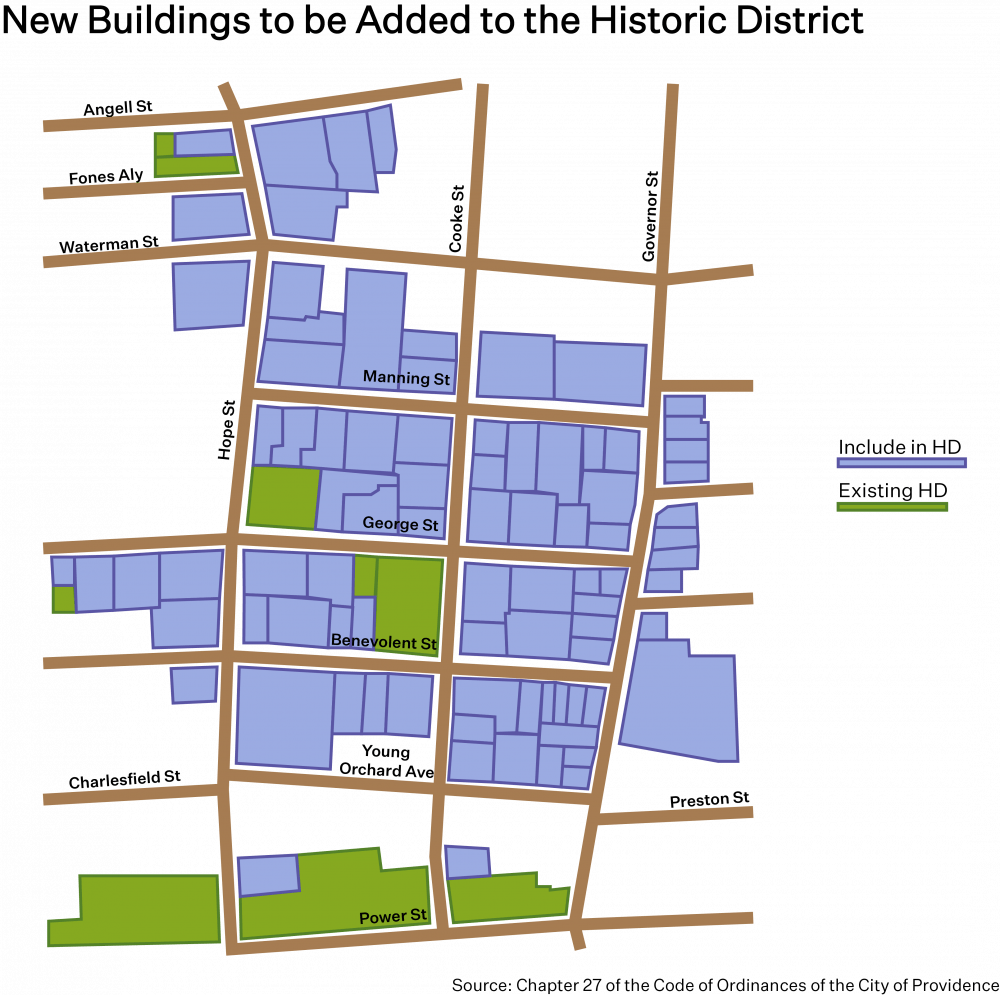

Three University-owned properties, including the Orwig Music Building, lay within the lines of the proposed historic district. The district would contain more than 90 properties, bounded on the east and west by Hope Street and Governor Street, respectively, and on the north and south by Angell Street and Power Street, respectively.

With historic district zoning rules in place, property owners are required to have any changes to the exterior of their buildings approved by the historic district commission run by the city planning department, said Brent Runyon, executive director of the Providence Preservation Society. Small changes, such as replacing a window or a door, need to be approved by the commission, as do large-scale changes such as demolishing a building entirely.

Under the current schedule, a public hearing will take place Feb. 24, during which community members can come forward in support of or in opposition to the ordinance. Andrew Teitz, a lawyer representing the University, came forward at a Jan. 27 meeting, raising a procedural objection to the scheduling of the hearing.

The objection was related to procedural rules of City Council committees, University Spokesperson Brian Clark wrote in an email to The Herald. The City Council committee on ordinances, guided by legal counsel, moved ahead with scheduling the hearing despite Teitz’s objection.

Clark, in an email to The Herald, confirmed that the University opposes any of its buildings being included in the district.

“We share the Providence Preservation Society’s commitment to preserving historic buildings on College Hill, support a reasonable expansion of the College Hill Historic District and appreciate the diligent community engagement process PPS has undertaken in recent years,” Clark wrote, “but we object to the boundaries proposed in PPS’s proposal for the district’s expansion.”

Much of the proposed district currently lies under I-2 zoning — zoning specifically designed for areas jutting out from educational institutions. That districting, Clark said, already requires “multiple layers of review” of the University’s plans that consider the history and character of the neighborhood.

“That process, and the City Plan Commission’s jurisdiction over properties within the I-2 District, already provide the necessary protection of the surrounding neighborhoods,” Clark wrote. “Another layer of review is unnecessary.”

But Runyon said that the existing regulation has “no teeth to it.”

“The City Plan Commission has no authority to say, ‘no, you cannot demolish that,’” he said.

Ward 1 City Councilman John Goncalves ’13 MA’15 told The Herald that additional regulation would not necessarily rule out further development.

“The city, generally speaking at this moment, is somewhat pro-development,” he said. “The historic district commission, while they do want to preserve the local historic districts, (is) certainly amenable to hearing what developers have to say.” Goncalves also noted in a message to The Herald that the commission is confined by what’s allowed legally.

Aside from the University, property owners who have communicated with the city regarding the proposed ordinance have largely expressed support, Runyon and Goncalves said.

“The party that seems to be heavily in opposition is Brown University,” Goncalves added. “The reason why they’re in opposition is … because it can limit their opportunity to expand in the way that they desire in the neighborhood.”

PPS, Runyon said, began crafting this district in 2013, following interest from property owners. While many properties on College Hill are on the National Register of Historic Places, that status offers no local protection in the event of proposed demolition. But the properties in the local historic district, which was created in 1960 and expanded in 1990, receive local protection from the historic district commission.

When the 2012 proposal for 257 Thayer called for the demolition of numerous buildings on the national historic register, residents elsewhere on College Hill approached PPS about creating a new local historic district, fearing their properties might be next. Residents requesting that their own homes be rezoned into a historic district, Runyon said, are a rarity. “Most people are happy to have restrictions on other people’s properties, but not their own,” he added.

After a draft of the plan for the new historic district — which at one point included dozens of University properties — was revised repeatedly to satisfy the University, residents and the city planning commission, the proposed ordinance came before a City Council committee.

The University has “engaged in discussion at multiple points” over the last decade regarding potential expansion of the College Hill Historic District, Clark said.

The relationship between East Siders and the University has long been fraught, said Rocket Drew ’22, advocacy chair of student group Housing Opportunities for People Everywhere. That the University intervened in the process doesn’t come as a surprise, according to both Runyon and Drew.

“Brown has the resources to put up a fight like that and doesn’t have the shame to hold back,” Drew said.

Goncalves, a lifelong Fox Point resident and a graduate of the University, related the University’s opposition to the ordinance with previous “challenges” the University’s expansion has created for College Hill residents.

Low-income communities and Black residents, Drew added, have also been historically displaced by the University’s expansion.

“There’s a drive from the greater community to protect the historic vibrancy of the community,” Goncalves said. “It’s a bummer that Brown is unwilling to budge.”

Still, the properties encompassed in the new district are mostly home to “middle and upper-middle class residents,” Runyon said. The properties included, he added, were largely chosen based on architectural and historical merit.

The net effects of historic districts are often unclear: While houses in historic districts retain value better than other properties in economic downturns, Runyon noted, the cost of maintaining a historic property is usually high.

Drew added that enabling the University to build in the area without more restrictions could hypothetically help the neighborhood: If the University were to expand with the purpose of building more on-campus housing while keeping the number of students it admits flat, it could take students out of the housing market in Providence, he said, dropping prices for other renters on the East Side.

Historical preservation, Runyon noted, can often be a “double-edged sword,” where preservation may be used to “exacerbate gentrification” or cause further displacement.

If the ordinance passes, its tangible impacts may prove “marginal,” Drew said, as the University may still find a way to litigate around the ordinance’s restrictions. Still, the ordinance could have other important consequences, such as “setting a precedent for holding Brown accountable.”

HOPE has not officially endorsed the zoning ordinance.

Goncalves echoed Drew’s comments: Expanding the new historic district could be an opportunity for the University to “right the wrongs” of its past.

“Expansion is important, but I think it’s also important to ensure their expansion is somewhat checked,” Goncalves said.

“We can’t undo the damage that Brown has done,” he said, referencing impacts including the destruction of homes and uprooting of communities. “But here’s an opportunity to do what we can to preserve what we have that’s left,”

The University, Clark said, will detail its position “more expansively” at the public hearing in late February.

Will Kubzansky was the 133rd editor-in-chief and president of the Brown Daily Herald. Previously, he served as a University News editor overseeing the admission & financial aid and staff & student labor beats. In his free time, he plays the guitar and soccer — both poorly.