On a Wednesday in June 1877, a procession of hundreds of students, alumni and community members marched across the campus of Brown University. Led by a marching band and a Providence sheriff, they crossed College, Benefit, Waterman and Main streets on the way to the First Baptist Meeting House.

The building filled quickly with an audience prepared to watch 59 students graduate in the University’s 109th annual commencement.

A popular and often boisterous affair, the commencement ceremony in Meeting House would have been packed with graduates and audience members alike, preparing to listen to the customary orations of the graduating men. The previous days had been filled with Commencement week events — speeches, sermons, alumni meetings — all building anticipation toward this final honor for the departing students.

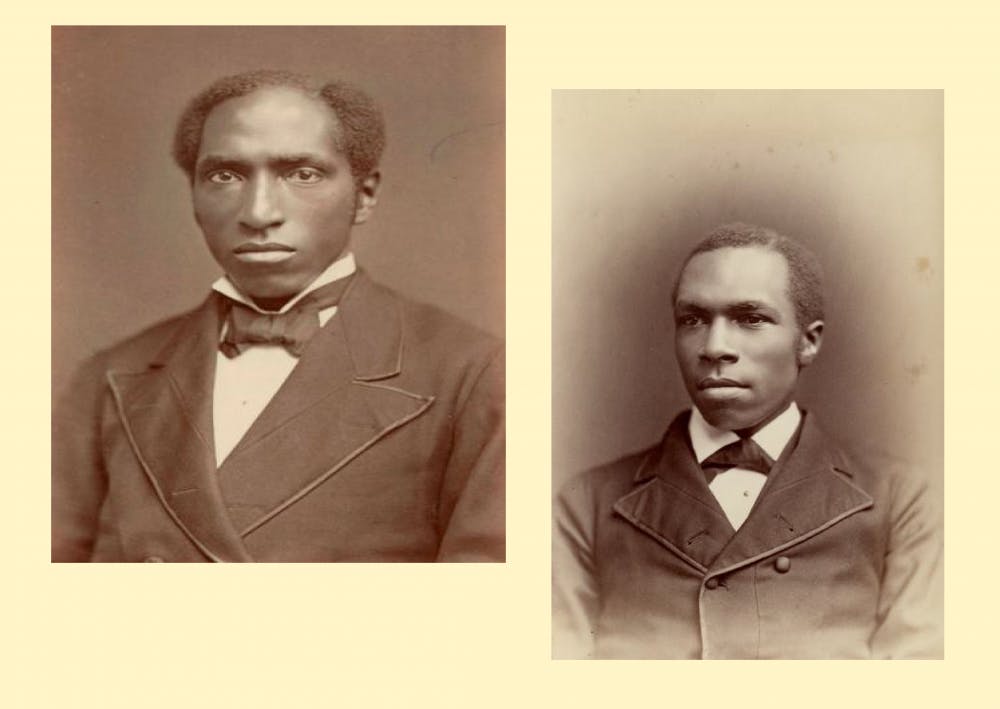

But this particular commencement ceremony was different from all those before it. For the first time, two Black graduates would accept their diplomas: Inman Page, class of 1877, and George Washington Milford, class of 1877.

Page, known for his skills in rhetoric, would give one of the commencement speeches in his elected role as class orator. He spoke on the merits of education and how cultivating minds, no matter a person’s lot in life, would continue to move America forward into a new age. These individuals, prepared with modern knowledge, would have the capabilities to lead the US forward — whether in politics or the literary canon.

“In a country like ours where similar opportunities for distinction and usefulness are presented to all, to the highest and the lowest alike, it is unnatural to suppose that with the advantages of education, which the schools and the universities afford aspirants for the highest political honors, will not be possessed of the qualities which are essential to true statesmanship,” Page said in his oration, which was immortalized in The Providence Press on June 15, 1877.

Trailblazers: Page and Milford take up their place at Brown

Black students began attending the University in the 1870s, and Page and Milford became the first recorded Black graduates in 1877, said University Archivist Jennifer Betts.

While the University does not have any admissions records for Page and Milford, nor do they know the exact year they began studying at Brown, they both “had the academic coursework in order to get in,” Betts said. They would have passed the annual June examinations required to secure admission to the University, and they would have been versed in subjects ranging from literature to philosophy.

Page and Milford were both accomplished men, but they still would have had a difficult time securing admission to Brown on account of their race. “I've wondered for a very long time how (they) got in,” said Ray Rickman, director of the nonprofit Stages of Freedom. “That’s always the question with anybody Black.”

Black students who were historically admitted to institutions like Brown were held to even higher standards than their white peers, Rickman explained. They would often have to be athletes or the children of prominent Black families to set themselves apart. “What they used to do is take the children of college presidents and administrators who look like they could be a college president of one of the Black schools,” Rickman said. “You have to be perfect, and then you have to stay perfect, too.”

It is unclear why exactly the University chose this specific time to expand their admission demographics, though “it was always something that was thought about at Brown,” Betts said. “There were a lot of discussions, in particular around slavery, over the years.”

“It's a strange phenomena,” Rickman said. “A school that practices discrimination for 120 years, absolute racial discrimination from 1764 forward, and then they let two (Black) people in. I just have question after question.”

From slavery to success: Page makes his way to College Hill and beyond

Inman Page was born into slavery in 1853 in Warrenton, Virginia where, until he was 10 years old, he worked as a house boy. When the Civil War began, Page and his family escaped, fleeing to Washington, D.C. to evade the Confederacy.

There, Page began his education, first studying at a private school for Black children then continuing to attend school at night while working to support his family. Soon after Howard University opened, he began working there to help level the ground of the newly constructed campus for 15 cents per hour so he could afford to enroll in the university’s classes.

In 1872, Page began his studies at Brown. “It was an incredible achievement at that time,” Rickman said.

Page faced considerable racism in his first two years at Brown. He was able to win the respect of his white classmates after winning an oration contest in his sophomore year. He continued to hone those skills throughout his time at Brown. Eventually, he was elected by his graduating class to give a speech at Commencement.

“Mr. Page did not receive his position as class orator from a chivalrous recognition of his race by his white associates, although the choice is nonetheless creditable to them,” said an 1877 article about Page’s speaking skills in The Providence Journal. “He is an orator of rare ability, speaking with weight and sententiousness without effort at display and at times rising to a profound and impressive eloquence.”

Page lived in Hope College, sharing Room 3 with Milford. He was also a member of the Baseball Club, and he wrote a history of his class in his junior year.

After graduating Brown, Page went on to have a successful career in education. Throughout his career he became the president of four colleges: the Lincoln Institute in Missouri, Western Baptist College in Kansas, Roger Williams University in Tennessee and Langston University in Oklahoma.

At the end of his career, Page served as principal of Douglass High School in Oklahoma City, where he died on Christmas Day 1935 at 81. His obituary honored his influence on education and emphasized the impact he had on Black students from all over the country.

“Some of the most outstanding educational leaders in Oklahoma today graduated under the inspiration and influence of ‘Old Man Ike,’ as his students affectionately called him,” the obituary, which was published in The Pittsburgh Courier, said. “Page was known and respected by all who knew him because of his stately bearing and natural dignity.”

The University memorialized Page’s legacy in 2018 when Page-Robinson Hall was named in his honor alongside Ethel Tremaine Robinson, class of 1905, who was the first Black woman to graduate from the Women’s College, which was renamed to Pembroke College in 1928.

From College Hill to D.C.: Milford pursues law with his Brown education

Born in 1852 in Virginia, George Washington Milford’s time at the University was filled with the same racism that Page faced. He often corresponded with journalist and abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison to request advice about succeeding in this university environment.

Milford was part of a club called “The Sliders,” and in the 1877 Liber Brunensis yearbook it is said that “he never slides in the track.” He also served as the historian for the class of 1877.

Milford’s life after his graduation from Brown is much less documented than Page’s. He attended law school at Howard University and went on to have a successful career as a lawyer in Washington, D.C., even arguing a case before the Supreme Court.

Page and Milford leave a lasting legacy

Though the admission of Page and Milford was a large step forward for the University, Black students still did not have equal admission opportunities to the University for years to come. Up until World War II, there were anywhere “from one to five Black males” in a class of students, Rickman said.

Nevertheless, Page and Milford influenced generations of Black students to pursue education at Brown and in the world beyond.

“Especially at a university like Brown, where it was a very white University (and) it tended to (have) more affluent students, to be the first (Black students) and to so visibly stand out I imagine took a lot of courage and strength,” Betts said. “They inspired generation after generation of African American students to pursue their education at Brown.”

On that day in 1877, before the graduating students progressed out of the Meeting House and onto the Main Green for a dinner and celebration, Page gave his oration. He spoke of his optimism for the future of American education as a great equalizer, enlightening immigrants from around the world. If they were to participate in and contribute to American culture and governance, he said, they must have access to the education that “is necessary for the promotion of the public weal.”

“The school house has always been an important factor in American life,” Page said. “Let it ever be cherished as the nurse of the great and the good; let its rich blessings flow alike to the huts of the poor and the palaces of the rich; let the just indignation of the whole country rest upon those who shall in any way abridge its privileges! Genius is not always the gift of those in fortunate circumstances.”

ADVERTISEMENT