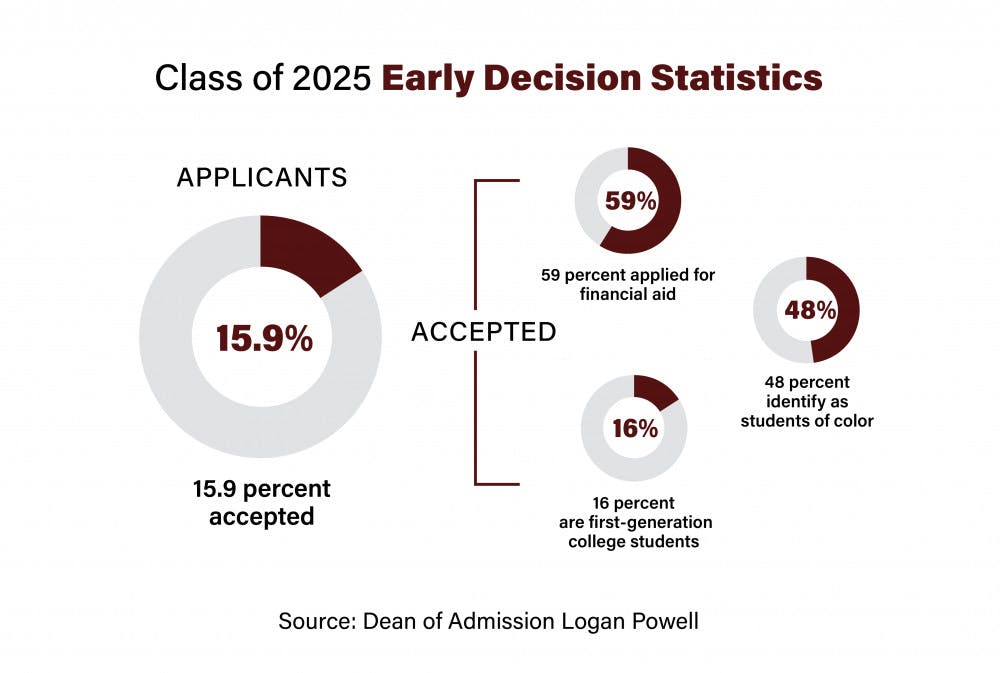

The University accepted a record-low 15.9 percent of early applicants to the class of 2025, down from 17.5 percent last year, according to Dean of Admissions Logan Powell. The number of accepted students and the number of applicants — 885 and 5,540, respectively — are the largest in University history.

Of the cohort of accepted students, 48 percent identified as students of color — another record high and an increase from 44 percent last year. Sixteen percent identify as first-generation college students, and 59 percent of students accepted applied for financial aid, both decreasing from 17 percent and 62 percent of the students admitted early to the class of 2024, respectively.

The rise in applicants stands in sharp contrast to trends across the country: Schools using the Common Application saw 8 percent fewer applications ahead of the Nov. 1 early application deadline compared to last year.

But the increase in applicants at the University is consistent with increases at “peer institutions” — highly selective universities and colleges, Powell said. Both Yale University and Dartmouth College saw their largest early applicant pools ever, with rises in pool size that outpaced that of Brown.

The high school seniors who chose to apply to a college early, Powell said, may have gravitated toward more highly selective institutions.

“Everything has changed for applicants now,” Powell said, adding that many were unable to visit college campuses in person or take standardized tests. He theorized that “a great many students decided perhaps ‘this is the year I’m going to take a shot at one of the highly selective institutions, then the chips will fall where they may,’” potentially allowing them to reassess their options before the Jan. 1 regular decision application deadline.

Still, Powell noted that the increase in applicants did not mark a decrease in quality of the applicant pool, adding that the foundation for the class of 2025 was strong.

“Our standards are exceptionally high as they always have been,” he said. “It was not a 22 percent increase in inadmissible applicants — it was a 22 percent increase in the quality we’re used to seeing.”

Thirty percent of applicants were deferred for review in the regular decision process.

The University additionally admitted 45 Questbridge scholars, and 19 students to the Program in Liberal Medical Education — a 10 percent acceptance rate to the program.

Students accepted to the class of 2025 represent 44 U.S. states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and 46 nations. The top foreign countries represented in the pool of accepted students were China, the United Kingdom, India, South Korea and Canada.

And despite a spring and fall largely without sports, the number of recruited athletes admitted early remained roughly stable in the early decision class compared to previous years, Powell said. The process of recruitment, he noted, actually moved faster than normal without junior or senior seasons to evaluate and no summer showcase events.

“As always, it was remarkably humbling that so many amazing students said that Brown is my first choice,” Powell said.

For the first time this century, the University also did not require students to submit a standardized test score — changing a key aspect of the admission process. While some students still submitted scores, Powell said, the students who did not were often stratified by geography. In some regions, he explained, nearly every applicant was able to submit a score; in others, that didn’t prove the case.

Applications of students who did not submit a test score, Powell said, received the same treatment as those who didn’t: application readers closely examined their transcripts, essays and recommendations, as well as their extracurricular activities.

“We were very deliberate in saying we couldn’t assume that a student was withholding information from us — that they had a test score they didn’t want us to see,” Powell said.

“There has never been a case, on the basis of the test score alone, that we’re either going to admit a student or deny a student,” he added.

The effects of last spring’s sudden halt due to the coronavirus pandemic also came into play: secondary schools, such as public schools in California and North Carolina, changed grading systems at the outset of virtual learning. While most schools with students applying to Brown had kept their standard grading systems, Powell said that admission officers assumed that students who had consistently received As throughout high school would continue receiving As, even through the pandemic.

For students who attend schools that shifted grading systems and who hit their stride later in high school but before the pandemic, the office relied on teacher recommendations and grades from the first quarter of senior year that came in a standard format. The Office of Admission sometimes called high schools to get the most up-to-date grades possible for students, ringing counselors as often as a few days in a row for updates.

“We wanted to give students every possibility to show their strength,” Powell explained.

Will Kubzansky was the 133rd editor-in-chief and president of the Brown Daily Herald. Previously, he served as a University News editor overseeing the admission & financial aid and staff & student labor beats. In his free time, he plays the guitar and soccer — both poorly.