As of January 2020, the University was only planning to offer three online courses for the spring semester: a creative nonfiction class, an English course called “Renegades, Reprobates and Castaways” and a course on the archeology of death in ancient Egypt.

But as COVID-19 edged closer to Providence, the large lectures in Salomon Center, small seminars in Page-Robison Hall and the lengthy lines for teaching assistant hours in the Center for Information Technology disappeared.

Those classes and resources, along with all other academic interactions, shifted to the same sphere as the three virtual classes.

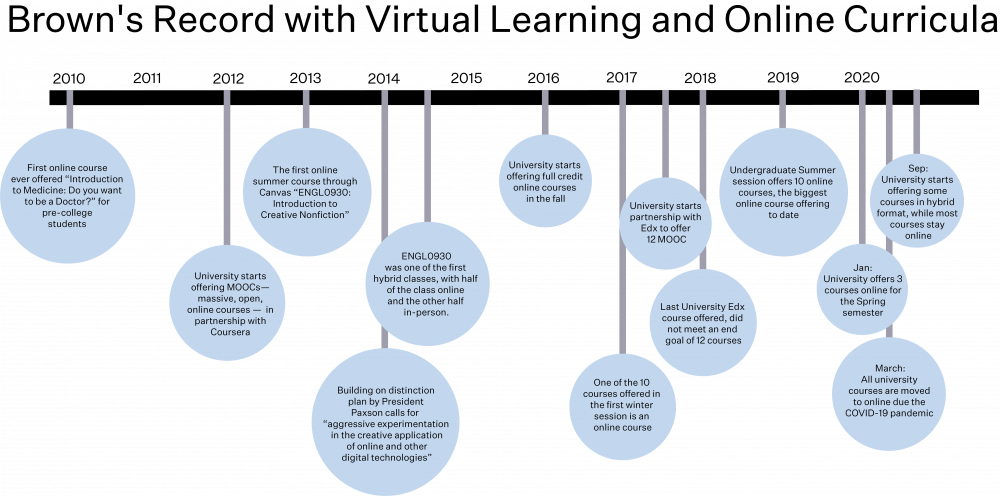

The COVID-19 crisis forced the University to dive headfirst into waters it had first explored more than 10 years earlier, when it offered its first online class. For the past eight months, the entire Brown community has been trying to navigate online learning, and wondering how these unusual semesters will shape the University’s long-term reality.

The road to online learning

University staff members started to think about offering online courses around 2005 and 2006, according to Vice President of Strategic Initiatives Karen Sibley MAT’81 P’07 P’12 P’17.

Sibley said that back then there was a lot of stigma surrounding online education, with many believing that it was inferior to in-person instruction.

In 2010, CEME0901 “Introduction to Medicine: So you think you want to be a doctor?” became the first online course ever offered at the University. Geared toward high schoolers, the summer pre-college course enrolled twice the number of students online than it had when it was offered on campus.

With its first online ventures, the University’s wanted to boost enrollment and increase its reach to different types of students within and beyond Providence, Sibley said. Early expansions in the University’s online instruction included more online summer pre-college course offerings and master’s programs in the School of Professional Studies.

The University also developed MOOCs — massive, open, online courses — in partnerships first with Coursera and edX, though these programs fizzled out in 2014 and 2018, respectively, as the University shifted focus toward its own online courses.

Undergraduates had their first opportunity to take an online class for credit in the summer of 2013, when the University offered ENGL 0930: “Introduction to Creative Nonfiction” online.

Since then, the University has gradually expanded its online offerings, especially during the summer and Wintersessions. In the fall of 2016, ENGL 0930 became the first online course to be offered in a regular term for full course credit. The first online Wintersession courses were offered in 2017.

2020: After an unexpected turn, professors regrouped for the fall

The University’s preexisting resources for online teaching at the Sheridan Center and Digital Learning and Design have been critical for the transition to online instruction in 2020, Sibley said.

But previous online courses offered by the University had been designed as such from the beginning — whereas the pivot to online learning in 2020 happened suddenly and required restructuring courses not initially planned to be online, according to Catherine Zabriskie, senior director of Digital Learning and Design.

“What we had to do in March was respond to an emergency,” Zabriskie said.

To plan for the fall, a group of professors, administrators and staff members served on a subcommittee of the University’s Academic Continuity Planning group to provide technical and pedagogical support for faculty as they planned for online, remote and hybrid instruction.

One of their initiatives was the Anchor Program, a summer course design program that brought together DLD staff with other staff from the Sheridan Center and the University Library to help faculty rethink their courses for online or hybrid formats. The institute helped faculty prepare for the fall and learn to use digital platforms, said Eric Kaldor, senior associate director for assessment and interdisciplinary teaching communities at the Sheridan Center and one of the staff members who led the Anchor Program.

“We didn't want people to repeat the spring experience (of) having to totally change the way we teach,” Kaldor said.

Spanning four days in the summer, the program was designed similarly to an online course offered on Canvas, said Melissa Kane, lead instructional designer at the Sheridan Center and a staff leader of the Anchor Project. Kane added that this aspect really allowed faculty to experience the student’s side of online learning.

In its first sessions the Anchor Project had 306 faculty participants and 36 student co-designers, Kaldor said. This represents around 40 percent of the faculty who are teaching this fall, which was a “huge success” for the project, Kane said. The program will be offered again to help faculty adapt their courses for the upcoming spring semester.

Ross Cheit, professor of international and public affairs and political science, took part in the Anchor Project to prepare to design his fall course, POLS 1050: “Ethics and Public Policy.”

At first, Cheit said that the program was “really daunting” because it made him realize that he had to restructure his teaching style. Cheit is used to teaching his class in a socratic format where he interacts with students by posing questions to them. Anchor played a “huge part” in his decision to prioritize interactions among students and add an asynchronous component to his class.

Sarah Evelyn, director of academic engagement for humanities and social sciences at the Library also helped with the Anchor Project. She added that the shift to mostly online instruction was not only a challenge for faculty, but also for the librarians.

“Using these different technologies to teach takes practice and learning. You can’t just take an in-person class and deliver it out of the box,” Evelyn said. Library staff “had to do our own learning as well as support campus needs while everybody was learning how to do their classes and do their work.”

Kane said that one of the other goals of Anchor was to create resilience and be prepared for the many uncertainties that the pandemic could bring. “The whole idea of resilience is being ready for face-to-face (instruction), being ready for hybrid, being ready for online, being ready for anything that comes at us,” Kane said.

Monica Linden, senior lecturer in neuroscience, who participated in Anchor, said that staff at the Sheridan Center, the Library and DLD “have been like the behind-the-scenes superheroes.” At the Anchor Institute, Linden also met a community of faculty going through similar course transitions. They have continued to meet over Zoom periodically.

Over the summer, students also had the chance to help faculty develop online syllabi through Short-term Projects for Research, Internships and Teaching awards.

To transition her two classes, NEUR 1030: “Neural Systems” and NEUR 1930N: “Region of Interest: An In-Depth Analysis of One Brain Area,” Linden worked with five students on SPRINT awards.

How far might online learning go?

Now, eight months since the start of the pandemic caused the first lockdowns in the United States, the University is about to end its first semester taught mostly remotely.

Even though the transition to remote instruction in March was very challenging for the University as a whole, Sibley said it has opened possibilities for online learning to be more widely accepted in the future.

With today’s normalization of online education, Brown can reach more audiences, including a larger pool of pre-college students and graduate students, as the University had begun to explore before the pandemic.

But Sibley sees even greater potential for online learning.

“We want to have 6,000 undergraduates on campus, but maybe we can serve 12,000 undergraduates and give the capacity for Brown learning to 6,000 (more) young people around the world,” Sibley said. “Your education at Brown is your engagement with people. And you can do that without necessarily being on campus.”

Still, many believe that the residential component is an integral part of Brown’s mission.

Mary Wright, executive director of the Sheridan Center, said that the learning that informally happens when students are interacting outside the classroom with professors or other students is key.

Cheit also believes in the value of the residential experience, adding that he misses interacting with students in the minutes before class and running into students on campus.

Johanna Hanink, associate professor of classics, who taught online summer classes for undergraduates before the pandemic, said that she enjoys teaching online classes and feels like they can be valuable, especially when students are taking just one course at a time. But she ultimately thinks that not all courses should be online.

“Doing everything online is sort of like eating exactly the same food all the time,” Hanink said. “Even if it’s a really healthy vegetable, you need some more variety, you need more kinds of intellectual stimulation rather than have everything be through a screen all the time.”

Stephen Foley ’74, associate professor of English and associate professor of comparative literature who taught some of the first online courses at the University before the pandemic during the summer session, said that online courses lend themselves well to the humanities.

“An online class in reading and writing gives people with those talents and interests … a format in which they can try and accomplish things very well,” Foley said.

Online classes could also reach Brown students studying abroad and allow faculty conducting research outside of Providence to continue teaching at the University, said Shankar Prasad, deputy provost for global engagement and strategic initiatives and leader of the subcommittee for online, remote and hybrid instruction for the Academic Continuity Planning group.

Linden and Cheit said that they “cannot wait” to return to teaching in a physical classroom, where they plan to incorporate aspects of online learning.

Linden said that she is considering continuing to offer virtual office hours since they are more flexible, making it easier for students to attend.

Cheit said that he might continue using breakout rooms, as they lead to more student-to-student interaction than his “talk to your neighbor” approach in the classroom. The virtual format also makes it easier to bring guest speakers to class. Cheit added that he plans to conduct surveys with his students to find out which aspects of his online teaching he should keep.

Still, despite the uncertain future of online education at Brown, all professors, staff and administrators interviewed by The Herald said they believe that the pandemic has required them to work hard to adapt to online learning, but also brought community members closer together.

“We have done a lot as a University,” Evelyn said. “I am really proud of all my colleagues and being able to shift even if there is a lot of personal and professional upheaval.”

ADVERTISEMENT