To get a ride downtown, you call the taxi dispatcher. To find a date, you sit at a bar. To share the details of your weekend, you call a friend. In 2007, this was life on a college campus.

But halfway through that year, the release of the first iPhone heralded a seismic cultural shift that no one anticipated. In September, a Brown Daily Herald article titled “Despite devotees, iPhone reception weak” announced the smartphone’s introduction to campus.

“I get the impression (the iPhone) will be a big Christmas thing,” Benjamin Schnapp ’07 MD ’11, an Apple store employee at the time, told The Herald. “I’ll come back for second semester, and a couple more people will have them.”

One year after The Herald’s story on the iPhone, Brown introduced Wifi for iPhone users. Now in its twelfth iteration, the iPhone and other smartphones rule life on campus — and wifi can be accessed everywhere, on every device.

Over the last decade, students on campus saw the world shrink to the palm of their hand, as new technologies transformed life at Brown and far beyond.

Congratulations! You have a new match!

When Danielle Marshak ’13, a former Herald General Manager, was a senior, mysterious advertisements popped up around campus. “These stickers started showing up on the elevators in the (Sciences Library). The elevator door would close and you would get a glimpse,” she said. “I remember being like, ‘what is Tinder?’”

Since then, dating apps have infiltrated college campuses, and Brown is no exception.

All of the dating apps common to Brown’s campus were released within the last ten years: Grindr in 2009, Tinder, Hinge and Coffee Meets Bagel in 2012, Bumble in 2014 and The League in 2015. Each purports to help people find their “perfect match” from the comfort of their own phone.

The majority of Tinder’s users are under the age of 25, according to the company’s end of 2019 press release. And these apps have become platforms for conversations that extend beyond dates and love. In 2019, the most popularly discussed topics on Tinder ranged from political figures like Elizabeth Warren and Greta Thunberg, to artists like Billie Eilish and pop-culture moments like the failed Fyre Festival.

Tinder gained traction among Brown students soon after its release, serving as a test school on the East Coast for the app, according to a 2013 story in The Herald. A 2015 article in The Herald reported that students found Tinder more approachable than previous website-based platforms, like Match.com. Then, students found Tinder far less stigmatized than other dating platforms, and most had never used anything other than Tinder.

Bumble, which requires women to message first in the app, has doubled the number of Brown users in the last year. In addition, the University’s users made 32 percent more first moves in 2019 compared to 2018. Bumble also provides platforms for friendship and business networking, called Bumble BFF and Bumble Bizz. “From 2018 to 2019 alone, there was a 90 percent growth in Bumble BFF users at Brown. This meaningful growth tells us that it’s been normalized for students to find friendships on campus through online tools like Bumble BFF,” a Bumble spokesperson wrote in an email to The Herald.

In recent years, the app has even introduced brand ambassadors on the University’s campus, including Isabel Riches ’22, who promotes the app and organizes events.“The real life dating world has a different vibe from a dating app, but it’s just people’s preferences. (The) misconception (is that) it’s inorganic if facilitated by technology, which isn’t the case,” Riches said.

But students and alums also attribute dating apps to a rise in “hookup” culture on campus.

Erin Chang ’23 views dating apps as more fun than anything else. “I don’t see people getting into long term stuff from it. If it boosts your self esteem, go for it,” she said.

Isaac Kianovsky ’23 agreed. “Sometimes it’s fun to look at pictures, but I don’t think there’s much to it,” he said.

Beyond dating apps, social media has added a new layer of stress to students interviewed by The Herald. “A lot of people like to showcase picturesque aspects of their relationships” on social media, Alyssa Steinbaum ’23 said. “It makes it seem like they’re better than they are.”

“It’s a different way to interact without seeing each other,” Tyler Jiang ’21 told The Herald. “It’s another thing to worry about.”

Pokeworks on Thayer says to pick up your order in 10 minutes.

Over the decade, convenience apps like Venmo and Snackpass have exploded in popularity. Approximately 4,500 University students have used Snackpass alone to order food in the last three months, wrote Kara Peruss ’18, a Snackpass representative, in an email to The Herald. Snackpass’s University user base has increased by more than 500 percent; when the app first launched, it attracted around 800 users in the first week and a half.

Vivian Van ’21 says that she uses the food ordering app two or three times a week. She appreciates the social aspect of the Snackpass app, especially the rewards feature that allows her to send sticker gifts after an order to friends “who I haven’t talked to in awhile or who are off meal plan who might want it.”

Meal-sharing and finances between friends have been made more convenient by Venmo, an app that allows users to transfer money. Alexis Rodriguez ’15 remembers the app growing popular during her senior year, even though it first launched in 2009. “I remember being stressed because I used to never have cash on me. Then, the ATM would only give $20s and you had to hope you’d get your change back,” she said. Among the apps of the last decade, “the biggest ones that changed our lives were definitely Venmo, Tinder for some people, and then Uber,” Rodriguez said.

To some students, the social feature of convenience apps can be “creepy,” said Sarah Bochicchio ’16. Especially with Venmo, she disliked that the transactions could be public. “I got it for a practical reason … but then it has this weird social media aspect to it. … It kind of gave me this window into the fact that all these apps are about surveillance, and it’s so constricting to have to perform for an audience when you’re just going out for dinner with someone.”

But Bochicchio also acknowledged that her feelings were not particularly common to other students during her time at Brown.

Jeff Huang, assistant professor of computer science, suggested that these apps continued to grow popular despite their “surveillance,” as Bochicchio put it, because “in general, technology has always been pushing this dimension of convenience. Convenience almost always trumps things like privacy or other concerns.”

The Class of 2020 has 1 new post share.

Facebook friend requests can be a prelude to lifelong college friendships, or they can function as a performative and meaningless social ritual.

“We all used Facebook to get to know each other before starting,” reflected Marshak. “Actually, one of the people who is my best friend today, she and I first had connected in the (Brown Class of 2013 Facebook) Group, … and we have been really close friends ever since.” The social media platform had only existed for five years at the time.

Orientation Facebook friendships have remained a tradition throughout the decade, as Rodriguez recalled a similar experience. “The first week (of school), you’d add 50 or 60 people. I remember when you would meet someone during orientation and you would exchange Facebooks,” she explained. Facebook Groups are still created for each matriculating class. Sometimes, the digitally founded connections served as beginnings to interpersonal friendships, though the friending frenzy was often fruitless.

Though Instagram was released to iOS in 2010 and Android in 2012, Marshak did not make an account until after graduating. “I think Instagram now is a much more social experience, but when it first started … people were using Instagram so that they could put cool filters on photos that they wanted to share on Facebook,” she said.

“I use social media mostly for scrolling, in between tasks throughout the day,” said Lauren Lee ’22. Scrolling has become a daily ritual, quietly filling every empty moment. “I also check it right after waking up and before going to sleep. Apple says I use about 40 min of it per day,” she added.

Lee, who signed up for Facebook on her thirteenth birthday, sees it as a way “to talk to friends, establish a solid image of my identity, and see what other people are up to.”

But others, including Sophie Nagle ’23, have found that the platforms increase the pressure of crafting a public image. “As the platforms have grown, I have felt a lot more pressure to actually post on my accounts.”

“Instagram was suddenly this thing where you could cultivate a version of yourself that other people couldn’t necessarily argue with and Snapchat was this voyeuristic window into what that meant,” Bochicchio said.

Social media’s rise to ubiquity has characterized the decade. As of June 2018, “75 percent of US 18-24 year olds are Instagram users,” according to the Business of Apps. But social media’s meteoric rise has finally begun to plateau and possibly evolve.

In the last year or so, users have begun taking more agency over their consumption of Facebook and Instagram posts. Apple introduced Screen Time in the fall of 2018 to appease increased consumer desire for mindful technology usage.

Now, Marshak uses Facebook and Instagram less than ever, setting a ten-minute timer to regulate her daily social media consumption. “When that limit comes up, sometimes I extend it, but I try to be mindful that I don’t know necessarily that it’s a super good use of my time.”

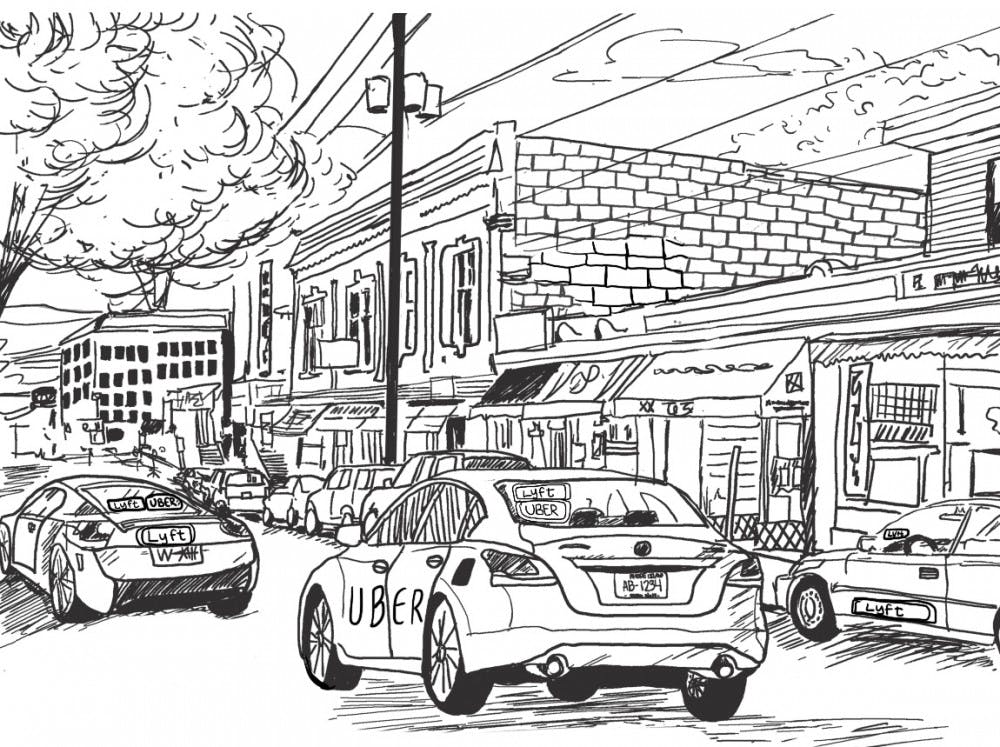

Your ride will be outside in 1 minute.

Running late? For students today, the answer may simply be calling an Uber or Lyft.

Uber was founded in 2009 and Lyft in 2012, but the early half of the decade was dominated on campus by the “taxi dispatch.”

“When I was at Brown, I didn’t have a car and I had truly traumatic taxi experiences, where the only way to get to the airport, if you didn’t want to take the train, was to call the taxi dispatch and reserve,” said Ashley Lordon ’10, who is currently a software engineer at Lyft. In her interview with The Herald, Lordon did not represent the views of her company. In addition to Lordon, many other students and alums have gone on to pursue careers at these companies, most notably the current CEO of Uber, Dara Khosrowshahi ’91.

Lordon recalled the taxi dispatch as “a nightmare. … It (was) like a negotiation that’s happening live, when you need to go. I definitely missed at least one flight, because I couldn’t get a ride.” Rodriguez described a similar distressing experience calling taxis during her first year at Brown.

Without ride-hailing apps, exploring the city was more difficult, Marshak said. “We knew there was this other side of Providence that had really good restaurants, but it was just a big hassle to get there.”

After coming to Brown from a small town in Connecticut, Brynn McGlinchey ’23 observed a greater need for transportation apps while living on campus. “It’s different in a big city; a big part of getting around is through these apps.”

In October 2018, The Herald reported that the number of total riders on RIPTA was the lowest it had been since the bus system saw an initial decline in users in 2013. At the time, Elizabeth Gentry, assistant vice president for business and financial services, said that this could potentially be attributed to the rise of ride-share apps.

Download complete.

“I think more than anything, the apps have brought out what has already existed in us,” Bochicchio said.

Rebecca Carcieri is an arts & culture editor. She is a senior from Warwick, Rhode Island studying political science.