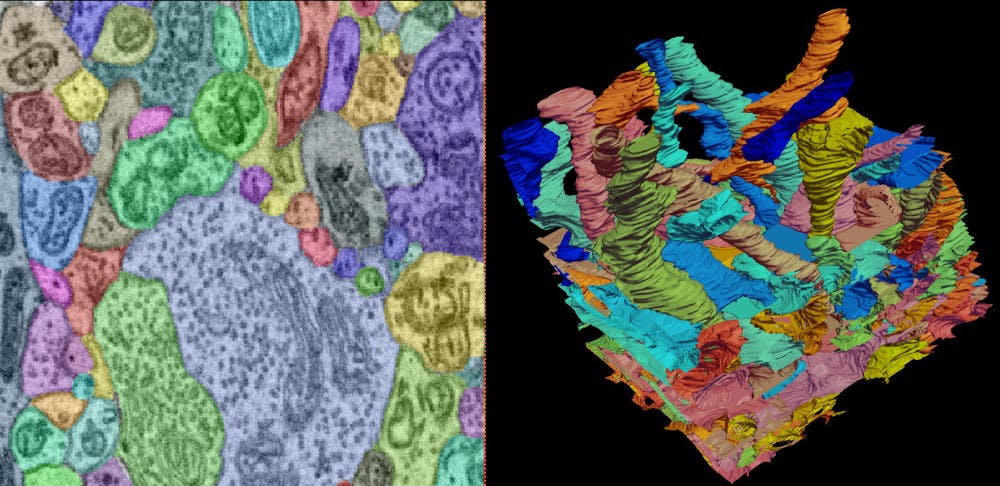

David Berson ’75, chair of neuroscience, studies how information travels from the eye to the brain. One of his recent projects examines the spidery forms of cells in the retina at the back of the eye, reconstructing their shapes and interconnections at a very fine scale. They’re shaped like spaghetti — cut across them and you see small rings, but cut the long way and you see cigar shapes, he said. Black and white pictures depict the microscopic cells in animal models, and Berson uses colors to digitally mark up the images as he moves through the tissue one picture at a time. Tracing these structures is a painstaking process, but thanks to a grant awarded last fall, Berson and his collaborator Thomas Serre hope a computer program will soon do the work for them.

Funding for innovative projects like this one is an element of the University’s Robert J. and Nancy D. Carney Institute for Brain Science, which was established by a $100 million gift from the Carneys last spring. Within the next decade, the donation should position Brown as one of the top two or three places to study the brain, according to Executive Director of the Institute Diane Lipscombe.

The University has now received an $100 million donation three times in its history, according to a press release, each leaving legacies at the University. One gift from Sidney Frank in 2004 supported undergraduate financial aid. Another from Warren Alpert in 2007 went to the medical school, the New York Times reported. The Carneys’ gift will only continue to draw more interest in brain science at the University, said Alycia Mosley Austin ’01, who studied neuroscience at Brown and now serves as executive coordinator of the interdisciplinary neuroscience program at the University of Rhode Island. “It’s not the pinnacle,” she added. “It’s the start of something that’s going to snowball.”

Blazing a trail in brain science

The Carneys’ donation will hopefully help generate cures for terrible brain diseases, said President Christina Paxson P’19. Formerly the Brown Institute for Brain Science, the center currently comprises scientists from across 23 departments: engineers, biologists, psychologists, doctors, cognitive scientists, neuroscientists, computer scientists and more collaborate to address disorders of the nervous system and to deepen understanding of the brain.

Josh Sanes, director of the Center for Brain Science at Harvard, considers the brain’s functioning to be the century’s greatest intellectual challenge. The Carneys’ gift is part of a national “wave of philanthropy” emerging as donors begin to view brain science as the next research frontier, he said. It will be especially transformative for Brown, whose brain science community is smaller than some.

The University had just begun to offer neuroscience as a concentration when Berson was an undergraduate studying psychology. It was one of the first curricular programs offered in the United States, he said. The explosion of interest in neuroscience happened nationally, but the University was near the forefront of this growth, partially because it was “blazing a trail” in neuroscience education, he said.

Three brain scientists still at the University authored an introductory neuroscience textbook whose first edition was published in 1996. That book is used at many peer institutions, said Marina Picciotto, deputy director of Yale’s Kavli Institute for Neuroscience. “Brown has been a major hub for neuroscience for a long time, and it’s really known across the field,” she added.

While the neuroscience program is separate from the Institute, the gift stabilizes a lot of long-standing research across departments at the University, preserving momentum while allowing scientists to move in a number of directions, said Christopher Moore, associate director of the Institute.

“Already we can see how the gift is energizing and elevating the work of the Institute,” Paxson said.

Cross-pollinating ideas

In a paper published this spring, Professor of Biology Kristi Wharton and her team observed a circuit flaw that may act as an early indicator of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis — a debilitating disease that rapidly erodes motor function, Wharton said. No effective treatments exist, but this study offers a site for possible therapeutics to act on. The findings emerged from a collaboration with Lipscombe’s lab, characteristic of the Institute’s interidsciplinary nature.

The Institute’s website lists close to 200 affiliated faculty members and 25 ongoing research projects. These projects span treatments for neurological disease and theory linking the brain to the mind. Scientists strive to identify genes linked to brain disorders, to understand the mechanisms behind human decision-making and to trace circuits of cells active in certain brain functions. This breadth is key to the Institute’s research, and helps foster interdisciplinary scholarship, Wharton said. The Institute is a “nucleating center,” providing the support for these collaborations to take hold.

The BrainGate consortium, which works with other universities across the country, fuses engineering and neuroscience to create technology that decodes brain signals to help people who have lost motor function. Their small devices, inserted beneath the skull, decode brain signals to help patients communicate or move. People who cannot move or speak have typed by guiding a cursor with their thoughts, and patients with paralysis have moved their hands again, according to publications by BrainGate researchers.

In another crossdisciplinary project, Associate Professor of Cognitive, Linguistic and Psychological Sciences Dina Amso uses computer vision to analyze children’s behavior. Infants play in a totally natural environment — a space filled with toys, books and colored mats, Amso said. But this SmartPlayroom also observes children’s behaviors, analyzing aspects like their movements and hand-eye coordination. Amso uses this information to investigate how a child’s environment can shape their brain development, posing questions about the effects of factors ranging from trauma to socioeconomic status.

Amso’s research is heavily reliant on the contributions of Serre, director of the University’s Center for Computation and Visualization. His work has also played a key role in Berson’s examination of retinal tissue. Serre’s Center often lets researchers make use of computer vision algorithms: Scientists will bring in animals like mice or zebrafish that have been treated or genetically engineered, and specialized equipment can track the animals’ behavior. The Carneys helped fund this rare technology even before their donation last spring, Serre said.

The Institute also facilitates collaborations by funding new spaces that encourage the cross-pollination of ideas, like its new central location at 164 Angell St. Computational neuroscience, for example, draws researchers from engineering, cognitive science, math and other areas at the University. Now they can have a space to brainstorm and work together, Serre said.

Funding from the Institute also supports pedagogy, fellowships and instrumentation. Andra Geana, a postdoctoral research associate, received funding from the Institute to teach a summer course on computational brain modeling. The Institute also offers funding to students through fellowships, according to Wharton — students working on ALS in different labs have benefitted from them. “The opportunity to learn in this environment is pretty much unparalleled,” Amso added. Wharton’s lab was able to buy new equipment pieces, which cost around one or two thousand dollars, with Institute funding. “If you want tools, they’re really good at getting you tools,” Geana said.

The Institute plans to hire about seven faculty members over the next decade, seeking people who might work across departments, Lipscombe said. Attracting and retaining excellent faculty is “really the most important thing we can do,” Paxson said.

The Carneys’ donation allows University brain scientists to think about the future of neuroscience rather than focusing on only their next research finding, Moore said. “It allows us to be strategic on a timescale that is actually the timescale of the biggest discoveries.”