On an August night in 2018 in Portsmouth, RI, seven high school sophomores were playing video games and eating whipped cream in their friend’s basement, discussing how to write their suicide prevention proposals into law.

Eight months later, their bill, which would require all school personnel in Rhode Island to receive standardized training in suicide prevention, is being held for further study in the state’s House and Senate.

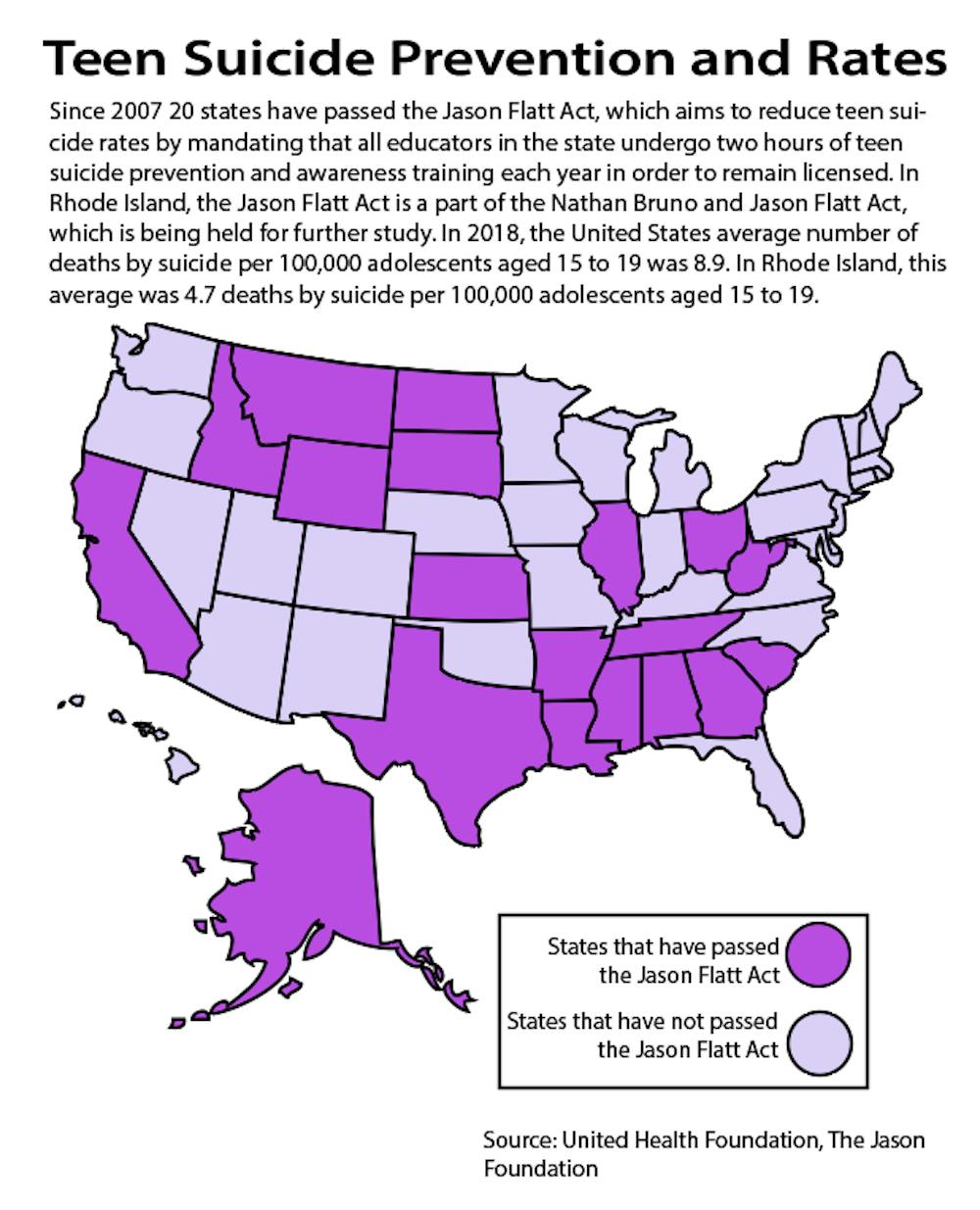

The bill, titled the “Nathan Bruno and Jason Flatt Act,” is partially named after Nathan Bruno, a former classmate of the boys’ who died by suicide in February 2018. Modeled after the Jason Flatt Act — which has already been passed in 20 states — the bill would put the Rhode Island Departments of Health and Education in charge of standardizing mandatory suicide prevention and awareness training for all staff.

In addition to the Jason Flatt Act component, the bill also proposes a protocol for student-staff conflict resolution and suggests changing the title of “school counselor” to “academic advisor.”

The Herald sat down with students and legislators to understand the motivations behind the bill.

No statewide policy

The bill would require suicide prevention trainings to take place during official training programs or professional development days. PD days are already built into the school calendar, but it is currently up to each school district to decide whether and how they want to train their school staff in suicide awareness and prevention.

“We don’t necessarily track at the state level how districts are spending their PD time,” said Megan Geoghegan, communications director of the Rhode Island Department of Education. For example, while some districts might prioritize mental health trainings, others might focus more time and resources on developing English teaching skills.

Statewide legislation passed in 1986 mandates suicide prevention education for high school students and those teachers responsible for providing this education. A 2017 law specifies the content and duration of these trainings.

But unlike the proposed Nathan Bruno and Jason Flatt Act, neither law requires all school personnel to be trained in suicide prevention. The Jason Flatt Act was first passed in Tennessee in 2007, requiring all teachers to undergo two hours of suicide awareness and prevention training each year in order to be licensed to teach in the state, according to the Jason Foundation’s website. This training can be completed through free online modules provided by the Jason Foundation, and it applies to all staff with a teaching license, which can include principals and school counselors.

Morgan Marks, national director of divisions and outreach/manager of operations at the Jason Foundation, said that the Foundation is aware of the efforts in the Ocean State to pass the Nathan Bruno and Jason Flatt Act. He added that while the Foundation does not help draft bills modeled on the Jason Flatt Act, they will testify in these bills’ favor if the sponsoring legislators ask them to do so. “We truly believe that it’s the right thing to do, especially (because) there is no cost added to (implementing the act),” he said.

Building the bill

The road that took the bill from a high schooler’s basement to the State House has been long and unexpected.

After Bruno’s passing early last year, the boys took to gathering regularly in each other’s basements, coping with the grieving process as a group. Steven Peterson, who had been their football coach, was often invited to these gatherings. With his help, the friends launched the Every Student Initiative, a platform that works toward preventing teen suicide by creating support systems in schools and communities. ESI is supported by "Be Great For Nate," a nonprofit started by Rick Bruno, Nathan Bruno’s father.

In August, the students presented ESI at a public event, which drew the attention of Sen. Dawn Euer, D-Newport, Jamestown, who proposed that the students turn their efforts into legislation. “It was kind of surreal to think we could do that,” said Angel Duclos, vice president of ESI, who was a close friend to Bruno. “But it made me think that I was accomplishing something great for my friend.”

In drafting the legislation, the students emphasized including the clause that changes the title of “school counselor” to “academic advisor.”

According to Geoghegan, school counselors are not required to be trained in suicide prevention and awareness. The students from ESI found the term “school counselor” confusing, because to them it suggested the contrary. “We were misled in the idea that our guidance counselor could help us at the moment,” Duclos said. Peterson added that the term “academic advisor” would have made things clearer for the students, who did not know who to turn to in the wake of Bruno’s passing.

Funding

RIDE currently allocates funds for mental health teacher trainings based on school districts’ demonstrated needs, Geoghegan said. These funds come from both the state and the federal government.

Last October, Rhode Island received a $2.5 million grant from the U.S. Department of Education dedicated to improving social and emotional well-being of students, The Herald previously reported. Previously, in September, the state received a $9 million grant from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to train school personnel in “mental and behavioral health services,” according to RIDE’s website.

On the state level, Gov. Gina Raimondo recommended that $590,000 of Rhode Island’s FY2020 budget go toward funding classroom-based “mental health/behavioral health” teacher trainings, which would be voluntary. At her State of the State Address this January, Raimondo announced that these funds would “provide educators with the training they need to support their students’ mental health needs.”

If the Nathan Bruno and Jason Flatt Act were to pass, it is unclear whether any of the state’s funding currently allocated for mental health trainings would help with its implementation.

Reactions to the bill

Rep. Terri-Denise Cortvriend, D-Portsmouth, Middletown, who is sponsoring the House bill, said that she sees this bill as a response to an increase in teenage suicide nationwide, and as part of a broader effort to advocate for mental health in public schools. She is hopeful that the bill will pass, adding that she is not aware of any opposition to the legislation.

In an email reviewed by The Herald, Ken Wagner, commissioner of education at RIDE, wrote to Sen. Hanna Gallo, D-Cranston, West Warwick that “while I am very supportive of these aims, I am concerned that this bill as written does not take into account efforts that are already happening to address youth suicide prevention (and) funding needed to support this effort.” Wagner cites the existing funding for mental health within Rhode Island schools, “which includes training … around suicide prevention.”

The students marvel that a year after their friend’s passing, legislators are working to pass a bill that they drafted in his name.

“How did it work?” Duclos asked himself during the interview, referring to the process of bringing the bill from its first inception to its current state. Peterson shrugged.

“It worked. Look at where we are now."

An earlier version of this article stated that the high school students, with the help of their football coach, launched a fundraiser titled “Be Great for Nate” and the Every Student Initiative. In fact, Nathan Bruno’s father, Rick Bruno, launched Be Great for Nate. The Herald regrets the error.

A graphic in the previous version of this article misidentified Rhode Island as a state that had passed the Jason Flatt Act. In fact, Rhode Island has not passed the Jason Flatt Act. The Herald regrets the error.