In early March, the Undergraduate Council of Students’ Elections Board held information sessions for prospective candidates to fill the council’s highest positions.

By the end of the month, Shanzé Tahir ’19 had been elected president of UCS, a body that “strives to actively and authentically pursue student interests,” according to its mission statement. About 35 percent of undergraduates voted in the presidential election, with 82 percent supporting Tahir over opponent Fabrice Guyot-Sionnest ’20.

Though student governing bodies have different responsibilities across the Ivy League, they each hold variations of an annual election process. The election cycle for student government typically lasts between two and three weeks at schools including Yale and Brown, or as long as four weeks, the maximum length permitted at Princeton. Elections are organized by groups of students ranging in size; at Princeton, they are led primarily by one elections manager whereas a committee of roughly 40 students coordinates elections at Penn.

Candidates

When Viet Nguyen ’17 won the 2016 UCS presidential election, he broke an eight-year streak of presidents elected with experience on the council — establishing a new trend that has continued since. For the past three years, the president of UCS has been elected without any prior service on the body.

“It’s just one of those things that happens,” said Kathryn Stack ’19, who has co-chaired the UCS Elections Board for the past two spring election cycles. “Most people come from some sort of leadership experience, though. It’s maybe just not in student government.”

Nguyen, for instance, played a large role in establishing what is now known as the First-Generation College and Low-Income Student Center before he became president. Both Chelse-Amoy Steele ’18, who succeeded Nguyen, and Tahir had previous leadership experience on campus. Steele co-founded the student group Mosiac+, while Tahir served as the chair of Brown Lecture Board and an executive board member of the Brown Muslim Students Association.

“I decided to run last year because I think UCS provides a platform to advocate for meaningful change on campus,” Tahir wrote in an email to The Herald.

Presidents from outside the council are not typical across student governments. At Harvard, for instance, outsider candidates for the presidency and vice presidency have lost to candidates with experience in 22 of the past 23 elections for its Undergraduate Council. In a notable exception, the president and vice president elected in fall 2013 had no experience on the Harvard UC and ran on a platform promising tomato basil ravioli soup at all meals and thicker toilet paper.

At Yale, candidates “almost always” have experience serving on the Yale College Council, said Heidi Dong, Yale CC vice president and chair of the Council Elections Commission. That experience is important to ensure continuity in the council’s projects, she added.

“It’s certainly not uncommon” for candidates vying for the top positions in Dartmouth’s Student Assembly to have experience, said Luke Cuomo, chair of the Election Planning and Advisory Committee, though “we don’t really do any target recruiting for candidates.”

Cornell’s Student Assembly requires that candidates at minimum apply to one of its committees before running for any office. That requirement serves “both to ensure that people … know what they’re getting into … (and) to make sure that if someone’s elected, they’re going to be engaged,” said Shashank Vura, Cornell SA’s director of elections.

For at least the past four years, Cornell has had two candidates for president in each election cycle, all of whom entered the race with experience on SA, according to coverage in the Cornell Daily Sun. Vura noted that extensive experience is not required to run for the presidency, though “one common stepping stone is a position called Executive Vice-President, which is often held by a junior.”

Vice presidents of Brown’s UCS have not vied for the presidency since the 2015 election, when Sazzy Gourley ’16 defeated two other candidates, though students with other UCS experience have run.

Campaigning

At Dartmouth, most candidates for president and vice president elect to campaign on a ticket, Cuomo said, though doing so is not required. Similarly, in past years at Yale, Penn and Columbia, candidates have been permitted to campaign together, though it is not required.

Harvard’s UC requires that potential presidents and vice presidents form tickets.

In contrast, coordinated campaigning is strictly prohibited at Brown.

“The idea is just (to) make it less (about the) popularity of a certain group of people,” said Katherine Barry ’19, who has co-chaired the UCS Elections Board for the past two spring election cycles.

Candidates for president and vice president of UCS may not run on tickets, nor may they speak about their platforms together.

“We had an issue (last year) where some people were going around the (Sharpe Refectory) together, speaking to their two different campaigns, but we don’t allow that,” Stack said.

Cornell similarly requires “all independent” tickets, Vura said. “Adding a level of partisanship … would only add divisiveness where it doesn’t need to be,” he added. “Even if it made elections a lot more competitive and got people a lot more involved, … I’m not sure if it would be that conducive to getting major accomplishments in a positive (manner).”

Student government election cycles also typically feature some amount of spending on campaign materials, with options for reimbursement.

At Brown, the limit is $40 or 100 “publicity points,” the value of which is outlined by the Elections Board. Candidates may contact the Student Activities Office to have their campaign budget funded if they have demonstrated financial need, according to the 2018 Elections Handbook.

“We just don’t want people who have unlimited funds available to them … to put others at a disadvantage by spending a ton of money on different campaign methods,” Barry said. “We want people to also not spend a ton of time on this — we want everyone to be on the same playing field in terms of how much time they have to put into the campaign.”

The $40 spending limit is on the lower side, comparable to the $50 limit at Penn, Cornell and Princeton.

At Harvard, each ticket may spend up to $400, according to the Harvard UC Constitution and Bylaws, while Yale caps spending at $100.

Though Dartmouth permits candidates for president and vice president to spend up to $200, “most candidates don’t usually use all the funding,” Cuomo said. “That’s because our elections aren’t usually too competitive, or because campaign season is short and they don’t have time to use it all.”

Engagement

Roughly 35 percent of the undergraduate student body at Brown cast ballots in the 2018 UCS presidential election. This marked a 17 percent increase from the 2017 race, when 18 percent of students cast ballots for Steele, who ran unopposed.

Contested elections and controversial candidates can spur higher turnout, Stack said.

Over the past four years, turnout at Brown peaked at 49 percent when Sazzy Gourley ’15 narrowly defeated two other candidates in the presidential race with 50.5 percent of the vote.

The 2017 UCS election, which featured uncontested races for every UCS position with a candidate, yielded the lowest turnout at Brown in the past four years, with about 22 percent of students casting a ballot.

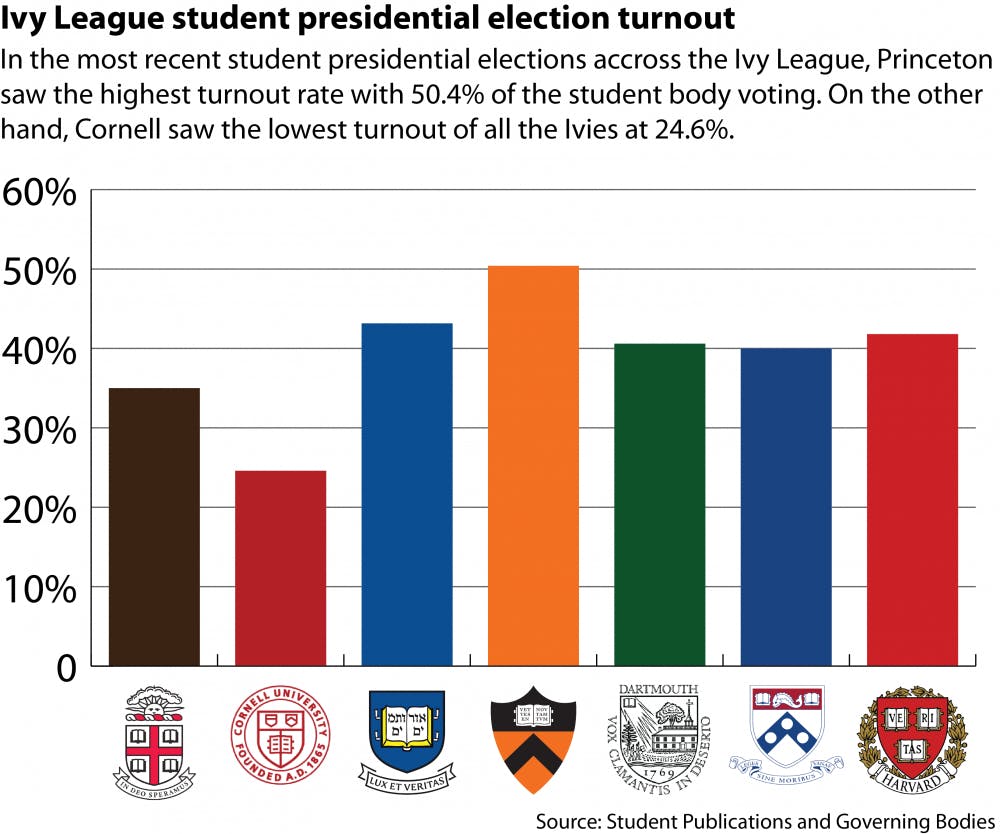

That turnout is one of the lowest in the past three years among Ivies whose turnout figures are publicly available in student newspapers. The only comparably low turnout rates occurred in Yale’s spring 2017 election, when 22.3 percent of undergraduates voted in a race that featured two candidates for president, and at Cornell, where turnout has ranged between 27 and 30 percent over the past three years.

Student governments engage in various efforts to encourage their student bodies to participate in elections, but turnout ultimately depends on a number of factors.

At Yale, 43 percent of undergraduates voted last spring, which is “really good turnout,” Dong said. “Part of that was because it was a competitive race and people were really campaigning, (and) … when students feel the YCC is really engaging with them, they are more in turn engaged with the YCC and more likely to participate in the voting process.”

Princeton, which holds elections for its executive committee in the winter, saw around 50.3 percent turnout last year.

“Last winter, we had four honor code referenda on the ballot,” which dealt with processes and punishments for honor code violations, and that “definitely pushes turnout,” said Laura Zecca, chief elections manager for Princeton’s Undergraduate Student Government. There were three candidates for president, and the candidate who won “did a fantastic job campaigning, so she really drummed up a lot of that voter engagement.”

Zecca, who assumed her position in February, said that Princeton USG also worked on a campaign that aimed to raise turnout to 50 percent for the council’s spring elections for representatives.

“In the past for spring elections, the turnout’s usually relatively low because they’re not the executive offices,” Zecca said. To combat low turnout, Princeton USG engaged in a Facebook campaign, sent emails, tabled in Princeton’s campus center and set up voting booths on campus, Zecca said.

“We didn’t get 50 percent, but I think we ended up getting about 33 percent, which was more than double what it had been in the year before,” Zecca said. “I’m planning for the winter elections for the executive positions to do something similar.”

Penn’s SA does not report exact turnout numbers, but turnout in the presidential and vice presidential races tends to be close to 40 percent, said Kiley Marron, vice chair for elections at Penn’s Nomination and Elections Committee.

“We have lots of discussions about how we can (get) a more educated electorate as well as keep encouraging more people to run,” Marron said.

To that end, the Nominations and Elections Committee launched an information session “to encourage (people) to run and maybe answer some questions,” Marron added.

At Brown, “we incentivize people to come to the debates … to hear about candidates’ platforms,” Barry said. The Elections Board also “tries to get student groups involved as much as possible … because a lot of people will vote” if their student group endorses a candidate, she added.

“We expect (student groups) to have discussed (endorsements) with their group members, and that gets the word out to more of those general body members,” Stack said.

Last year, UCS also reduced the number of student signatures that candidates for president and vice president are required to collect from 400 to 200, in an effort to make running for office more accessible.

Barry noted at the time that the new requirement “probably wouldn’t get more people to run this year” — the change was made after the required information sessions for potential candidates — but the reduced requirement could have an effect this year.

Furthermore, UCS established a Communications Committee this year, which is “creating now more avenues for transparency for the whole student body,” said Communications Director Sofia Jimenez ’21, who heads the committee.

The committee is working to “solidify our communications protocol,” Jimenez said, adding that she sees their work as relevant to elections. “We do want to encourage students to be more participatory within the process of elections,” she said.

After each election cycle, the Elections Board also takes time to re-evaluate their policies and improve, Barry said.

“We always ask the board and talk among ourselves (about) what sorts of things could’ve gone better, … and then we look at those notes in the beginning of the year and try to restructure a little bit,” she said.