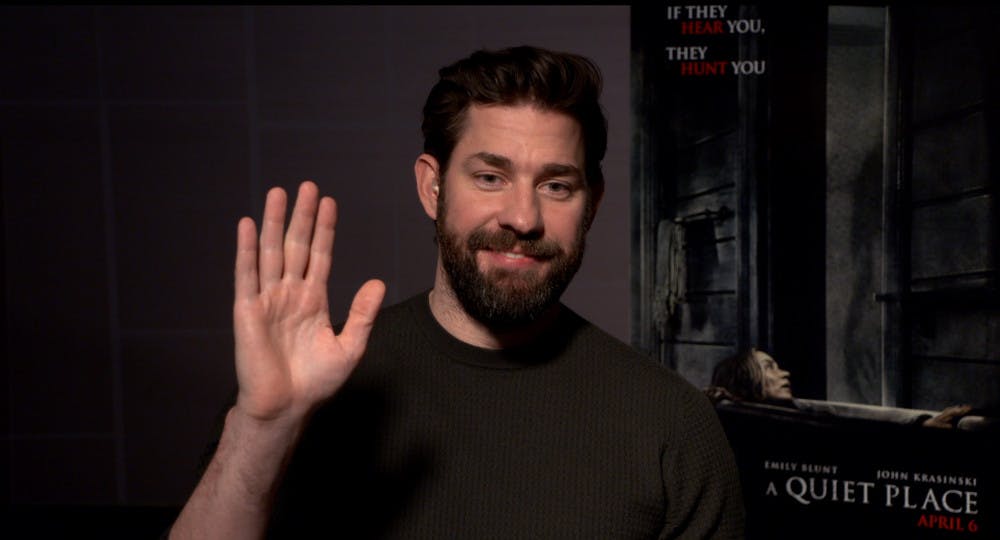

For nearly a decade, John Krasinski ’01 was best known for his role as Dunder Mifflin paper salesman Jim Halpert on the NBC comedy “The Office,” playing pranks on Dwight and staring down the camera with a knowing expression and a charming shrug. But in his third directorial endeavor, “A Quiet Place,” Krasinski breaks away from comedy with a horror film set in an apocalyptic world where even the slightest noise results in a violent death by human-eating creatures. The film, released today, underscores the importance of family in a pervasively threatening environment. Krasinski crafts the story of two parents — played by Krasinski and his wife Emily Blunt — and their young children who must learn to fiercely protect one another in the fight for survival.

Reading the script for “A Quiet Place” just three weeks after the birth of his second daughter, Krasinski said the thread of family immediately hit home. “I was already in a state of terror about whether or not I was a good enough father,” he said in a conference interview with The Herald and other university publications. Imagining being a father in a nightmare world who is so dedicated to keeping his children alive elevated the meaning of parenting to him, he added.

This focus on family and parenting weaves throughout the entire plot as a central theme that parallels the terror, Krasinski said. Though the film has its jumpy moments, he wanted the audience to experience fear in direct correlation with love for the family. “If I can make you fall in love with this family, then you’ll be scared because you don’t want anything to happen to them,” he said.

As actor, producer and writer, Krasinski donned various hats, in addition to his role as a father in real life, to cement the family’s interdependence and center the rest of the movie around their inseparability. For him, the film is “a love letter to (his) kids.”

Krasinski also regularly turned to his on-screen and real-life wife Blunt for her input and ideas. Although it was their first time working together on the same set, Blunt went above and beyond in being a collaborative contributor, giving Krasinski notes on the script and shots and being present whether or not her character acted in the scene, he said.

Together, Krasinski and Blunt generated ideas about how to inject horror into the film. As a self-proclaimed “scaredy-cat,” Krasinski drew from his own instincts to decide what fear factors would play most effectively in each scene. While writing, Krasinski would imagine himself in the scene and think about what would scare him most and then write that very image or action into the script.

Silence plays a critical role in the film — nearly the entire first half of the screen time contains no dialogue, and the entire script is only 67 pages. But as the cast shot these scenes, Krasinski said he learned about the value of such stillness in a distractingly noisy world. “We just sat in the forest and we listened, and it was really powerful to have all of these ambient sounds around you,” he said. Krasinski has since started taking his daughter outside to “just look up at the sky and listen.”

The family in the movie goes to painstaking lengths to remain silent and ensure safety by putting sand down when they walk through the forest, painting floorboards so that they don’t creak and communicating through American Sign Language. The cast learned ASL together from deaf actress Millicent Simmonds, who played the deaf daughter in the film.

“There’s no better teacher for ASL than Millie because she was so kind and gentle,” Krasinski said. “I’ve never had someone take in all of me when we were communicating.” Simmonds taught the cast about how each individual has their own version of sign language — for example, the father, who focuses on keeping the children safe, has very curt and short signs, whereas the mother, who wants to give the children a larger life, has more poetic gestures. Krasinski cited his biggest regret about his directing experience as having not learned more sign language, as he believes that “there’s no more beautiful language.”

Krasinski fondly recalled how his community at Brown opened up a world of exposure, impacting his work today “in every single way.” Every week for all four of his years at Brown, he would ask his group of friends to give him an album or a movie recommendation, helping him grow from a high schooler “who had never seen a movie that wasn’t in a Cineplex or listened to music that wasn’t on the radio” to the actor, director and producer he is today.

“I could talk about this forever and I would probably start crying,” Krasinski said. “I legitimately would not be half the person that you see in front of you if it were not for Brown. … I wish I could go back.”