When an ancient Mayan scribe put paint to fig bark sometime around the turn of the 13th century, he hardly could have imagined that his bark sheets would ultimately make their way around the world — via the Internet, no less.

But such has been the journey of the Grolier Codex, a Maya astrological manuscript, which can now be considered the oldest known book produced in the Americas, after recent research by a quartet of researchers eliminated questions about the manuscript’s legitimacy.

In a 50-page paper published in the journal Maya Archaeology — which also included a pull-out facsimile of the codex — the team analyzed the content and physical structure of the text, offering evidence to counter each prior criticism.

“We felt that this document — which had been criticized and discounted by a number of scholars to the extent that it was not held by some people to be genuine — needed to be studied,” said Stephen Houston, professor of social science, director of the University’s program in early cultures and one of the paper’s authors. “We needed to get together and review the evidence with time, with more dispassion and determine what we now believe to be true.”

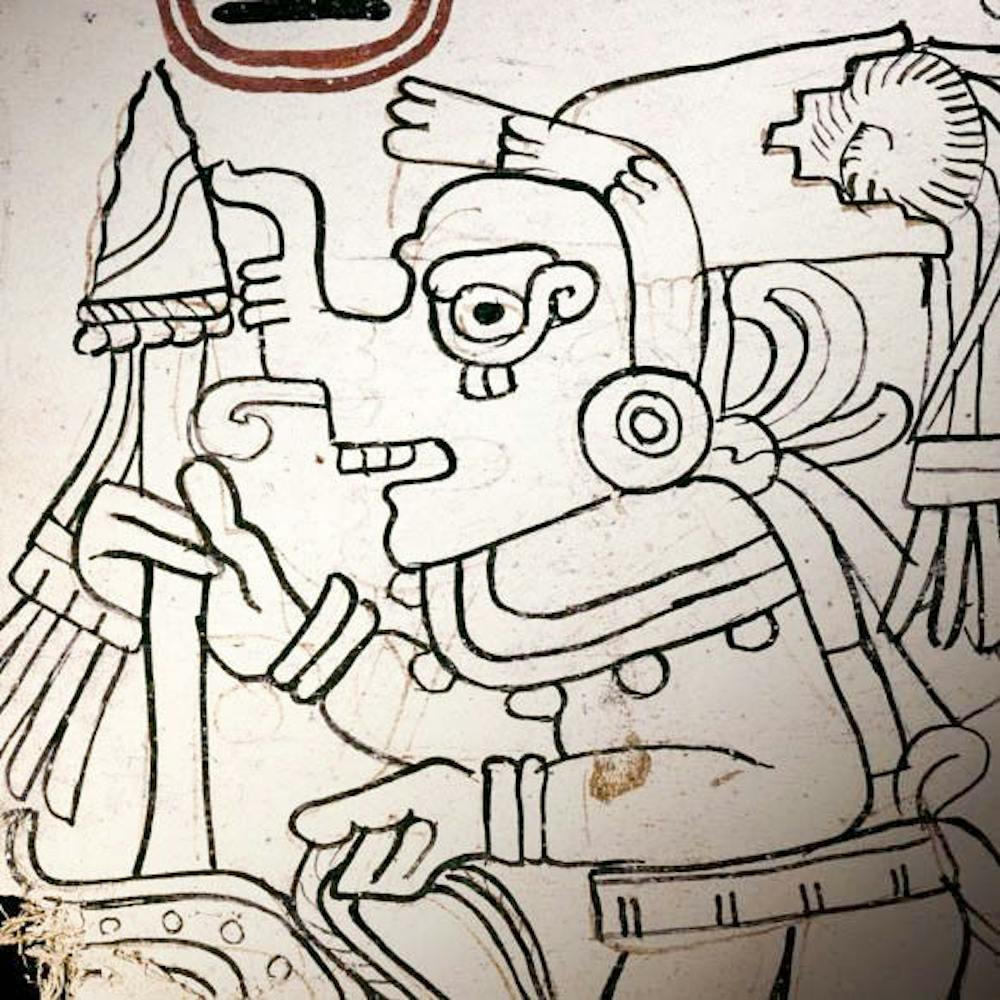

The codex is essentially a calendar, documenting the cycles of Venus and associating these cycles with different Maya deities to assist in divination efforts. Each sheet features the lines, bars and glyphs of the Maya writing system — which Houston has played a significant role in deciphering, earning a MacArthur Genius Grant for his work.

“The book itself isn’t a work of surpassing beauty,” Houston said. “It’s a kind of everyday book used by a priest in a Maya town a few centuries before the Spanish conquest. What makes it interesting is that it’s a book of the sort the Maya had by the thousand.”

In the mid-1960s, looters found the text in a cave in the Yucatan, and through a series of transactions, it ended up in the Grolier Club in New York. Because of these dubious circumstances surrounding its discovery, scholars clashed on its authenticity for decades. Some say the prolonged debate over the codex hinged more on personal bias than historical evidence.

Whatever the nature of the suspicions, Houston and the other researchers used every tool available — radiocarbon dating of the paper, chemical testing of the traditional “Maya blue” ink and rigorous analysis of the iconography — to dispel them.

Perhaps most convincing is the fact that some of the images in the codex have only become known to Mayanists over the past decade of research. As an example, Andrew Scherer, associate professor of anthropology and archaeology, pointed to a human figure on the second-to-last page of the facsimile, which shows a man with a cleft in his head that has been filled with maize. This image has only been recently understood to be shorthand for the spirit of a mountain.

“It is simply impossible that at the time the Grolier was supposedly forged, extremely detailed information, only known within the last five to 10 years, would have been in possession of a forger in Mexico in 1964-1965,” Houston said.

The text’s authenticity is particularly significant because only three other pre-Columbian texts from the Americas have been discovered. “The Spanish actively burned texts as a way of cultural colonization and evangelization,” said Mallory Matsumoto GS, adding that the humid climate in the Maya region is hardly conducive to book preservation.

These aren’t just discoveries impacting Maya researchers: “Knowledge from the academic sphere generated by scholars is being sort of integrated into Maya communities and taken up and used by them in certain ways,” Matsumoto said. “The most famous example is the Pan-Mayan movement in Guatemala. Drawing off studies of the pre-Columbian past, you get this sense of collective Maya identity that did not exist before.”

The knowledge surrounding this ancient culture — and the modern world’s ability to understand thoughts recorded over 800 years ago — is constantly growing.

“Every couple of months, if not sooner, there’s a new text, a new site excavated, and those are rapidly circulated by email. We know things long before they appear in print,” Houston said. “It’s an exuberantly fun field; there are always new things to learn. The Maya for me have an endless capacity to surprise.”