Once upon a time, there was a poplar. It was a Lombardy poplar. And everyone loved it very much. People would come and take cuttings and plant it and play botanist. And in 1784, one man took a cutting, packed it for America and sailed.

Then one day, in 1803, a man from Rhode Island came to Brown University and said, “Let me plant you.” The tree nodded implicitly, as trees do. And he planted the poplars in two great rows on College Hill, long deforested. And they grew and grew. But by 1840, they had grown too high, because Lombardy poplars, as it turns out, grow too quickly, are unsuitable to humid climate and have shallow root systems. And no one was happy.

But the people learned. By 1840, the first American elms were seen sprouting from the front lawn. These newly planted trees were long-living, fast-growing and stable. They multiplied and grew inseparable from Brown’s campus, unifying its communities and transforming its outdoor spaces into canopied agoras. And everyone was happy. Until 2014.

I have come to know and appreciate the celebrated history of Brown’s campus. Many of its buildings boast founding dates and narratives far in the past but nonetheless well documented. But trees bear no blueprints, placards or dates. Like buildings, they punctuate space, but often lack historical documentation. They grow, lose limbs and sprout new ones. They witness events as they unfold but are voiceless in the process.

As Brown continues to update its campus, renovate its buildings and lay walkways, rapidly altering its footprint on College Hill, it appears we have learned nothing from our past. We have, instead, chosen to disregard historical significance and modernize our campus at much too fast a pace. We have chosen not to build upon an existing history, but rather to write a new one.

The history of Brown’s landscape is riddled with mistakes. In 1877, the University planned to construct a dormitory on the Main Green, running the full length of George Street. The city erupted in contempt. One “tax-payer” wrote to the Providence Journal on Nov. 17 of that year declaring that “in all these years, the public has cherished the conviction that no hands would ever be permitted to mar the form and beauty of the college grounds.” Another “citizen” wrote two days later that “it ruins the campus, so far as the purposes are concerned.” President Ezekial Robinson took heed, plans were changed, and Slater Hall — which did not break up the Green — was built two years later.

Brown also has had successes. When President William Faunce wished to expand and develop Brown’s campus, he contacted landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, designer of Central Park. Unable to unify the campus through architectural design due to the wide variety of historical styles, he did so through landscape design. He proposed additional curved pathways, first seen on the Quiet Green in an 1857 print by F.O. Freeman. These paths, in the Picturesque style, provided natural walkways that complemented the contours of the maturing elms. All bore rounded corners, now a hallmark of paths on campus. Olmsted despised when people cut corners.

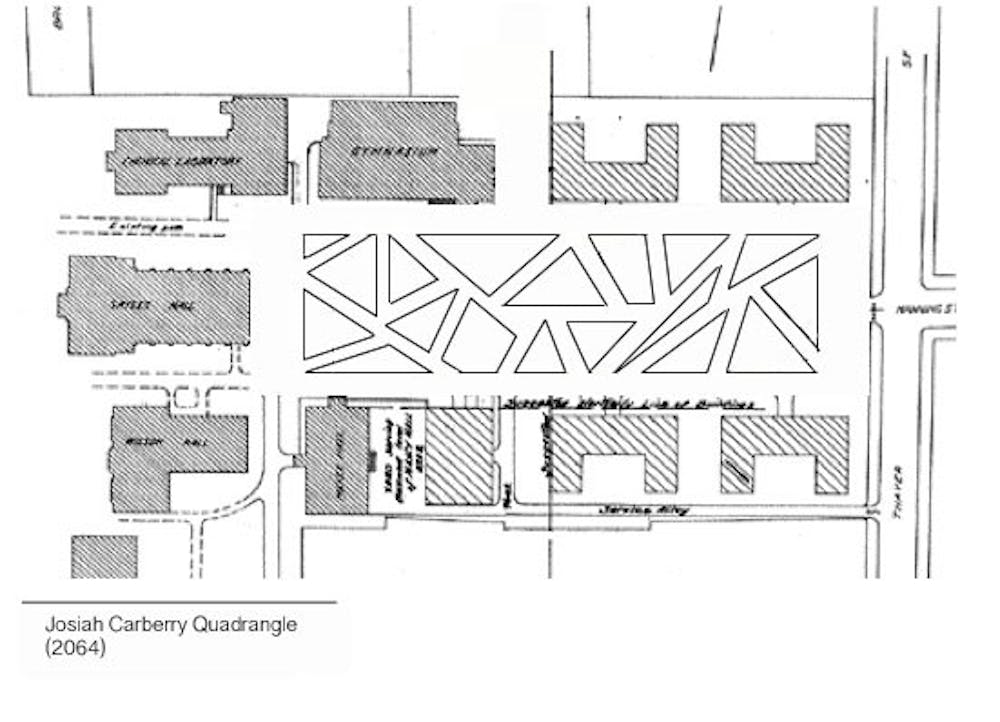

Current design practices, however, disregard the long legacy of landscaping at Brown and are building a campus for the future that is devoid of history. The new criss-cross pathway seen outside the Building for Environmental Research and Teaching, for example, appears to be from a build-a-landscape catalogue rather than a historically conscious design firm. Though it abuts Lincoln Field, it resembles no aspect of Olmsted’s principles.

Even when recent campus additions do attempt to communicate with history, they ultimately fail. “The Walk” brings to fruition a part of Olmsted’s 1901 plan to connect Pembroke College with the University — then distinct schools — but it leaves behind the most important lessons of his designs. With its parallel paths and boxed lawns, “The Walk” creates awkward spaces that divide rather than encourage a community experience. It has none of the obvious benefits of a central thoroughfare, which allows for a large combined space, as seen in Olmsted’s “Poet’s Walk” in Central Park. Nor does it subtly direct movement or enhance the scenery of the campus.

These paths, with their modern and socio-historically unjustifiable geometry, both fail to create a cohesive campus and negate the history of our space. It is one thing to create a space that works in the short term. It is another to create one that is true to the past, to Brown’s mission and to its continuing history. Unfortunately, it appears that the University is more concerned with efficiency and modernity than with feel, preservation and meaning. As we continue to design spaces looking toward the future, it is important to preserve, protect and contribute to the historical narrative embedded in our landscape.

In 1901 Faunce wrote, “(the) heterogeneousness, which we share with most New England colleges, is certainly picturesque. … But it is now time for some definite plan of architectural development.” As Brown celebrates 250 years, our history can be remembered through structure and design. Yes, we must innovate, but not without reflection and purpose. Our campus unifies us, and we must remember that.

In 1803, Lombardy poplars were in style. In 2014, geometric paths are. Maybe in 40 years, we’ll tear up these walkways. We can call it the lesson of the paths, or something like that.

Evan Sweren ’15 is a senior at Brown.

ADVERTISEMENT