Intact blood cells may no longer be needed to understand the composition of human blood samples, according to a recent study led by William Accomando PhD’13, who is now a research fellow at the Harvard School of Public Health.

This research could eventually be used to help monitor HIV patients without having to use fresh blood, wrote Karl Kelsey, professor of epidemiology, in an email to The Herald.

In the study, Accomando and his team determined a new way to profile white blood cells by using the cells’ DNA. The conventional method of counting the number of these disease-fighting cells in the bloodstream requires fresh blood and tissue, he said. “With our approach, all you need is any blood sample stored any way.”

This work is particularly important because many laboratories have “tons of blood samples stored up in freezers,” Accomando said.

When frozen, cells can burst and “thus the information of the proportional cell-type composition is lost,” wrote Karin Michels, an associate professor of epidemiology at the Harvard School of Public Health who was not involved in the study, in an email to The Herald.

Though conventional approaches would not be able to determine the number of white blood cells in these samples, the new technique can, Accomando said.

The conventional method involves using “surface markers” on the membrane of whole white blood cells to count them, Kelsey wrote in an email to The Herald. “Using our method, one can do the same thing without having to preserve the membrane.”

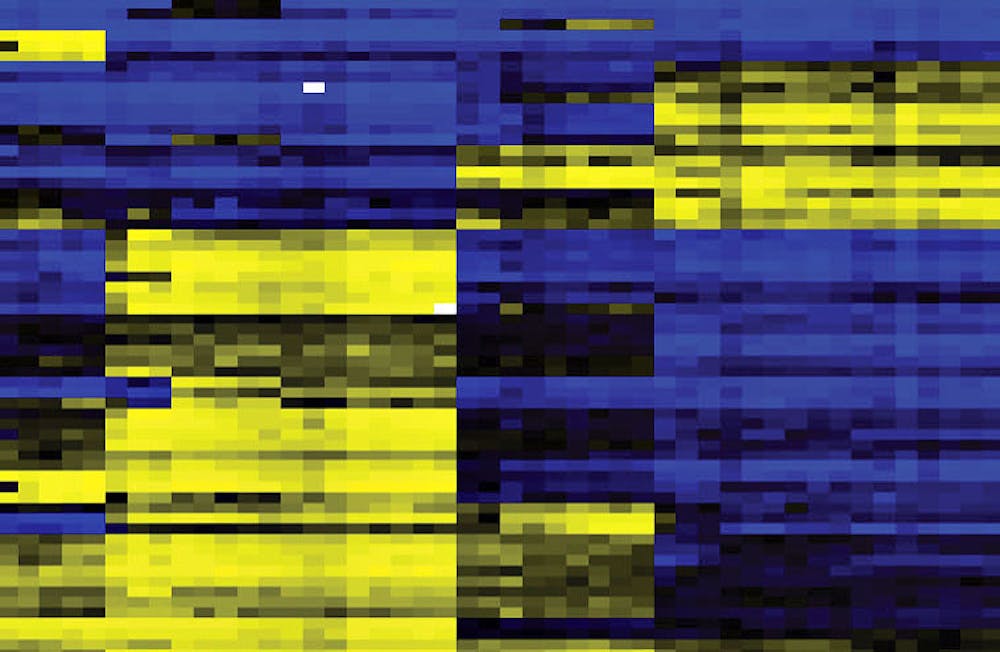

Instead of searching for surface makers, the new method scans for particular methylation sites that are unique to the DNA of white blood cells, Accomando said. “We are taking advantage of … what we know about DNA.”

To use the new method, researchers first obtain a blood sample and isolate the DNA within it, Accomando said. Next, researchers analyze methylation markers on the DNA, which create a specific profile of cell type since they indicate which stretches of DNA are turned off and turned on.

This process has “evolved to the point where we can use multiple methylation markers” to detect the DNA of white blood cells, Accomando added. He noted that since DNA is the template off of which cells are constructed, it is a more reliable source of information about a cell than just surface markers.

“It can really be used to detect and quantify any type of cell,” Accomando said, referring to the broader implications of his work.

This new technology has the potential to phase out the conventional method — flow cytometry — of detecting proportions of white blood cells, Kelsey wrote.

With regards to the medical implications of his work, Accomando said the new method for analyzing blood cells “is not yet a diagnosis tool.” But he and others are already using the method in their research, he said, adding that it can be a “great tool for finding relationships between exposure and diseases.”

Michels wrote that the method is “most useful in epidemiologic research with large cohorts (that) have frozen blood samples.”

Since the researchers’ new approach is very different from conventional methods, it may take time for the medical community to accept it. “A challenge still going forward is convincing the older generation immunologists … that this new method … is just as good as the previous methods,” Accomando said.

The present study began as Accomando’s thesis when he was at the Graduate School, Kelsey wrote.

“When I was first starting grad school, I was impressed by the fact that we can distinguish different (cell) types with methylation sites at all,” Accomando said.

ADVERTISEMENT