The University will require all sophomores to enroll in one of the four highest-priced meal plans beginning in the 2019-20 academic year in an effort to reduce food insecurity, according to a campus-wide email sent by Dean of the College Rashid Zia ’01 and Vice President for Campus Life Eric Estes.

Some undergraduates responded to the new requirement in the form of a widely-circulated letter, criticizing the changes for limiting student choice and imposing burdens on those with dietary restrictions.

Following the pushback, the University announced more changes on Thursday, including moving the start date of meal plans up to August 31, providing lunch and dinner during senior week at no extra cost, piloting a meal gap program for “students experiencing temporary food insecurity” and starting a dining working group which will seek to build food options that better fit student schedules.

The University will also begin providing meals over spring break at no extra cost to all students on meal plans, according to the original announcement May 24.

Working group recommendations and findings

These changes follow recommendations made by the Working Group on Food Security, which assessed “the existence, scope and origins of food insecurity on our campus,” according to the announcement. The group was comprised of students, faculty and staff.

Previously, sophomores could opt out of a meal plan, but starting in the fall, they will be required to choose between the four highest priced meal plans: 20 meals per week, Flex 460, 14 meals per week and Flex 330. The 20 meals per week and Flex 460 plans are each priced at $5,550, while the 14 meals per week and Flex 330 plans cost $5,226. First-years must enroll in one of the two highest meal plans, a requirement implemented in fall 2018, The Herald previously reported.

In a survey distributed to the Brown community, the working group found that 28 percent of undergraduates did not have enough to eat at some point in the past three months. In addition, 30 percent of sophomores reported experiencing food insecurity compared to 15 percent of first-year students. The working group attributed this difference in reported food security to the requirement that first-year students choose one of the two highest meal plans.

Food insecurity can impede students’ ability to succeed academically at the University, said Marisa Quinn, chief of staff to the provost and a member of the working group. The working group made its recommendations because members “were persuaded that students were devoting a lot of time and energy … to thinking about where they were going to get their next meal, and that’s a drain on being able to thrive as a student here,” she said.

Quinn added that “two-thirds of (sophomores) were already enrolled in meal plan, and a large percentage of them were on that more comprehensive plan,” making the sophomore meal plan requirement a natural extension of the requirement for first-years.

“Looking at the data, (University leadership saw) how the first-year meal plan changes last year had worked,” Zia said. “We felt it was our obligation, our responsibility, to help make this change that would help to best ensure that the hundreds of students who experienced food insecurity on this campus this year would be less likely to do so in the future.”

The University will also encourage sophomores to opt into one of the two highest meal plans, though they will still offer them the option of the smaller 14 meals per week and Flex 330 plans.

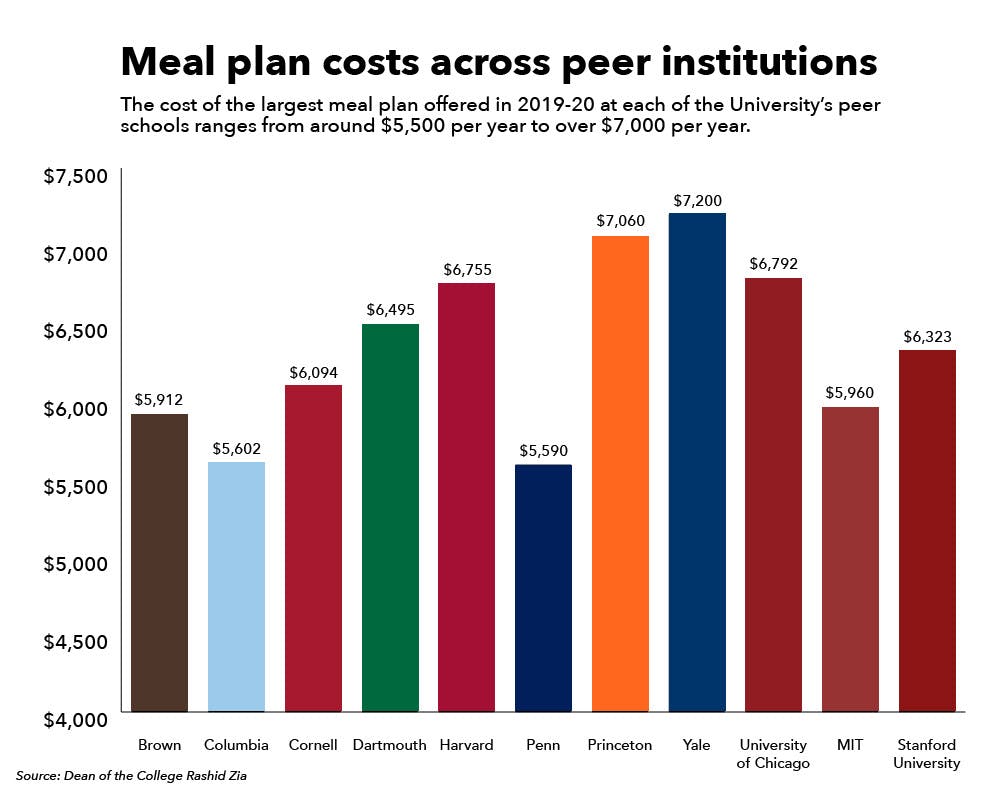

The working group examined practices at other peer institutions when crafting their recommendations, Quinn said, adding that many of the University’s peer institutions require that sophomores to stay on meal plan as well.

Dartmouth, Harvard and Yale each require second-year students residing on campus to be on meal plan, and Princeton requires a meal plan for all second-year students, according to data reviewed by The Herald. Meal plan requirements were unclear for Columbia, Cornell and Penn.

Student pushback

In response to the changes, a group of rising sophomores wrote a letter to Zia and Estes expressing concern with the new meal plan requirement. The letter had over 700 signatures as of press time.

The authors of the letter wrote that requiring sophomores to be on a meal plan “imposes restriction on student choice and freedom,” which is particularly limiting for students with dietary restrictions or those who observe religious practices.

Estes said that Dining Services at the University already seeks to accommodate students with dietary restrictions and will continue to do so under the new meal plan requirement. “Dining (Services) recognizes that students will have a range of dietary concerns, and there is already an existing process to work with students,” he said. Students with dining accommodation requests work with Dining Services to “find a reasonable solution or accommodation,” he added.

The authors of the letter also wrote that the meal plan options for sophomores “pose a significant financial cost to many students.”

The authors cited research from the Economic Policy Institute, “which totals monthly food costs for a single adult in the Providence metro area to be $276.” Using this statistic, the authors concluded that in 7.5 months — the approximate time of meal plan coverage — a student off meal plan would pay $2,070 in food costs, compared to $5,226 for the second highest meal plan.

Neev Parikh ’22, who circulated the original letter, added that the way meal plans are priced incentivizes students to pay for the most expensive options. Of the four available options to sophomores, the two most expensive plans cost less per credit.

For students on financial aid, the cost of attendance and their scholarships factor in the price of the highest meal plan, said Dean of Financial Aid Jim Tilton. “If (students) pay less for their meals, we still have included the total amount of the maximum meals as part of the scholarship, so they might have additional scholarship left over.”

Parikh also said that as an international student, cooking off meal plan would be a way for him to feel more connected to his culture. “I hope the University understands why we want the right to cook and why we are protesting against this sweeping requirement” for sophomores, he said.

Chiara Bellomo ’22 added that many students prefer to enjoy their meals at untraditional times when some dining halls may be closed.

In an email to the Brown community Thursday, Zia and Estes acknowledged “that food security and dining options are complex issues that engender strong reactions. We have and will continue to share student feedback with our colleagues in Dining Services to help inform their work moving forward.”

Moving forward

Looking forward, the working group is exploring “the possibility of locating a co-op or an at-cost grocery store here on campus” to give upperclassmen alternative options to obtain food, Quinn said.

According to the executive summary of the working group’s findings and recommendations, the group also plans to “assess the feasibility of requiring all students living on campus to have an unlimited meal plan.”

The working group will continue to solicit feedback from the community in the coming year through another ongoing committee including “representatives from dining and a diversity of students from across the campus to think about how our dining services really support the needs of students, to address their curricular and co-curricular demands,” Quinn said.

ADVERTISEMENT